Half of all patents for genes from marine species owned by one company

A single corporation owns half of all existing patents for genes from marine species, according to a new study.

Researchers found that nearly every genetic sequence from ocean organisms on record, belonged to companies, universities and other entities located in just 10 countries.

Genetic information from deep-sea creatures has immense potential value for medicine, food and even fuels, and the scientists behind the analysis expressed concern that this wealth is not being fairly distributed.

This dominance has taken hold despite the Nagoya Protocol – an international framework meant to prevent nations or companies monopolising the world’s genetic resources.

“In areas beyond national jurisdiction – roughly two-thirds of the ocean, or half the Earth’s surface – no such mechanism currently exists,” Dr Robert Blasiak of Stockholm Resilience Centre told The Independent.

In their analysis, published in the journal Science Advances, Dr Blasiak and his colleagues identified nearly 13,000 genetic sequences from marine species that have been patented.

Not only had German-based BASF – the world’s largest chemical producer – registered 47 per cent of all patented marine sequences, actors located or headquartered in 10 countries had registered 98 per cent of these sequences.

The two other major nations leading the charge on marine patents were the US and Japan.

“Registering patents is not cheap or easy, and many of these patents will likely end up being a ‘loss’,” said Dr Blasiak. “I think companies are often looking for the next aspirin or the like that will represent a ground-breaking advance for the biotech industry, and be a goldmine of sorts for the patent holder.”

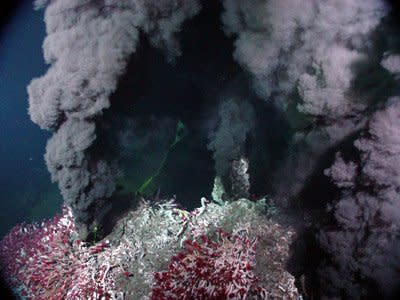

Marine genetic information is particularly valuable as many creatures found at the bottom of the world’s oceans have evolved to cope with extreme environments, such as hydrothermal vents.

Adaptation to extremes of pressure, acidity, heat and absence of light have given these deep-sea creatures genetic codes that are often vastly different to organisms found on land.

These can be ripe for commercial applications. BASF for example, was able to successfully isolate of genes from marine microbes responsible for omega 3 production.

Known as the substances in fish oil responsible for an array of beneficial health effects, omega 3 actually finds its way into fish due to its presence in microorganisms and plankton that they eat.

After isolating the relevant genes, BASF scientists were able to splice them into rapeseed, so they could produce canola oil from the plants that contains omega 3.

“It’s almost like science fiction,” said Dr Blasiak. “As I understand it, there is a push to have this fortified canola oil on the market for human consumption by 2020.”

A spokesperson from BASF said the vast majority of marine genetic sequences included in patent applications by the corporation are from publicly available databases, and noted that "publicly known sequences cannot be protected by patents".

"BASF has applied for patents to a large extent for special self-developed use-cases in which these sequences are used. Examples of such applications are increasing the yield of crop plants."

The desire to take advantage of the sea’s precious resources is understandable, and by 2025 the global market for marine biotechnology is expected to reach $6.4bn (£4.8bn).

However, as there is currently no Nagoya Protocol to protect the vast areas beyond national jurisdiction there is a danger that marine resources will be disproportionately exploited by isolated actors.

Countries that have taken part in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) have committed to promoting marine technology "for the benefit of all parties concerned on an equitable basis".

As 27 of the 30 countries that have patented marine genes are parties to UNCLOS, the researchers suggested this should drive greater equity and fairness in the distribution of these resources.

"Equity is deeply embedded within UNCLOS and the language of the sustainable development goals," said Dr Colette Wabnitz, a marine scientist at the University of British Columbia and co-author on the study.

As it stands, there is no obligation for companies like BASF to disclose the provenance of their genetic material, making it difficult to tackle these issues.

International negotiations on a new UN treaty are set to begin in September that will cover conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in areas of the sea not covered by the Nagoya Protocol.

"Ensuring that the process moves forward in an inclusive manner means that states should increase their commitments to disclose the geographic origin of marine genetic resources, and promote greater international participation in discovering and using the benefits of marine biodiversity,” said Dr Wabnitz.

According to the scientists, this also means the handful of companies with disproportionate influence must be involved in these negotitations.

“Everything should be done, for instance, to try to get representatives of BASF to contribute their expertise to this process,” said Dr Blasiak.

“They are clearly leaders in this landscape of actors and have substantial knowledge to draw on that can help the negotiations move forward in a practical manner.”

The BASF spokesperson said: "The sustainable use of resources including marine resources is very important to BASF and we are fully supportive of the aims of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Nagoya Protocol and UNCLOS".

Yahoo News

Yahoo News