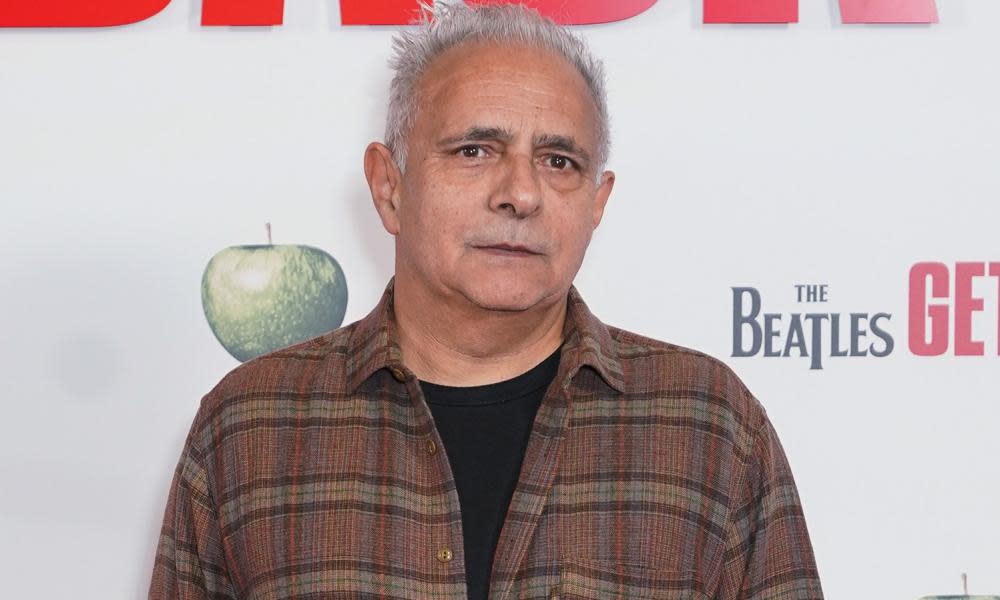

Hanif Kureishi helped liberate British Asians from their imposed identities

We had been messaging each other on Boxing Day, trying to fix a date for a drink. Then all went silent. I assumed that Hanif Kureishi was too busy enjoying himself in Rome. Only later did I discover that he had had a fall that had left him almost paralysed and in hospital.

Kureishi’s hospital admission has made headlines around the world, not least because, incapacitated though he is, he has from his hospital bed produced a series of Twitter threads, collected on his Substack newsletter, a stream of consciousness about his condition at once poignant, profound, playful and laced with black humour. Unable to type, Kureishi FaceTimes his son Carlo, who writes out his thoughts before publishing them. Whatever his physical debilitation, Kureishi’s mind remains as sharp as ever.

For me, the shock of Kureishi’s incapacitation is not just that such a terrible misfortune should befall a friend. It is also that long before I knew him as a friend, I treasured Kureishi, like many of my generation of British Asians, as someone who helped us discover our voice and our place in an often hostile society. CLR James and Sivanandan, Paul Gilroy and James Baldwin – many writers politically shaped my understanding of race, class and identity, but Kureishi spoke far more viscerally to my hopes and fears, desires and aspirations. His words were as much a part of my soundtrack as those of Jerry Dammers, Patti Smith and Prince.

Britain was a different country then. It was one in which racist stabbings and firebombings were almost as regular as the morning milk round, in which “Paki bashing” was a national sport. It was also a country in which the image of Asians was that of an unassertive people who, unlike African-Caribbeans, seemed to take their kicks and licks and were too scared to look folk in the eye.

That was never the real story, of course. From strikes such as Imperial Typewriters in 1974 and Grunwick, three years later, both led by Asian women, to the defence of Southall against fascists in 1979 and the Bradford 12 campaign, Asians were not simply looking racists in the eye but punching back.

It was to this generation of Asians, kicking out against both racism and the conventional image of what an Asian should be, to whom Kureishi spoke. His Asians were not timid or deferential but as cocksure, streetwise and sexually charged as Kureishi himself.

I can still remember the shock, pleasure and recognition I felt the first time I watched the groundbreaking 1985 film My Beautiful Laundrette, written by Kureishi and directed by Stephen Frears. It told the story of a gay love affair across racial lines. It may be difficult to recognise now just how transgressive that storyline was at a time not just of remorseless racism but also of deeply embedded homophobia, a nation cut through by the Aids panic and with the controversy over section 28 about to burst.

What stayed with me, however, was not just the love affair between Daniel Day-Lewis’s Johnny and Gordon Warnecke’s Omar, but equally the moment when the landlord Nasser evicts a black tenant. Johnny protests that he should not treat another black person so cruelly. “I am a professional businessman, not a professional Pakistani,” Nasser curtly tells him.

It was not that I identified with the loathsome Nasser. It was just that with that one line, Kureishi broke out of the prison of identity imposed both by racism and by antiracist notions of ethnic belonging. Asians not as victims or “nice”, but as people with the same range of views and attitudes, of progressiveness and nastiness, as any other group. Long before the debate about whether Rishi Sunak or Suella Braverman have “betrayed” their community with their reactionary views, Kureishi punctured the hollowness of such claims.

And, three years before the controversy over The Satanic Verses, Kureishi incurred the wrath of Islamists, and not just in Britain. “About a hundred people, all men, all middle-aged, would turn up every Friday,” Kureishi remembers of protests in New York “to demonstrate outside cinemas shouting, ‘No homosexuals in Pakistan’.”

Kureishi’s refusal to present all Asian characters in a good light upset many on the left, too. “It was the first time that I remember the left and Muslim fundamentalists joining hands,” Kureishi recalled many years later. “Islamic critics would say, ‘You shouldn’t wash dirty linen in public’. And the left would say, ‘You should not attack minority communities’.” These are sentiments that have only strengthened in the years since.

The Rushdie affair was the real watershed. “It changed the direction of my writing,” Kureishi recalled later. “I was interested in race, in identity, in mixture, but never in Islam. The fatwa changed all that.”

In the years that followed, books such as The Black Album and My Son the Fanatic, the first of which was turned into a play, the second into a film, explored the tensions of the new Islamism.

There is a subtlety to Kureishi’s fiction that is often missing from the wider social discourse about Islamism and jihadism.

The Islamists in Kureishi’s stories are not first-generation immigrants, bemoaning a world taken from them, but their children, yearning for an Islam they have never known. It is less a clash of civilisations than a war of generations, the first generation desiring material prosperity, the second seeking to fill a spiritual void.

“The fundamentalists I met,” Kureishi once observed in a striking turn of phrase, “were educated, integrated, as English as David Beckham. But they thought that England was a cesspit. They had no idea what life would be like in an Islamic country but they yearned for everything sharia. And they had a kind of Islam that would have disgusted their parents.”

Kureishi wrote his novels and screenplays for the same reason that I read them and watched them: to tear up the old cultural map and to discover where we stood in the new landscape we were creating. Looking back over Kureishi’s work over the past half century is to follow the changing contours of that landscape.

One can only hope that we can continue to be able to do so. And I can only hope, too, that sometime soon we can have that drink.

• Kenan Malik is an Observer columnist. Join him at 8pm on Tuesday 31 January for a livestreamed Guardian Live event where he will be talking about his new book, Not So Black and White. Tickets available here.

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a letter of up to 250 words to be considered for publication, email it to us at observer.letters@observer.co.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News