What happens to the global publicity titans if advertising no longer pays?

Not so long ago a bearish Sir Martin Sorrell berated the advertising industry for its unrealistic “Don Draperish optimism” in the face of tough times, in a reference to hit TV series Mad Men and its depiction of the halcyon days and excesses of 1960s adland. Now it is the next generation, of Sorrell and his “math men” – the builders of global empires designed to churn out profits – that is now perhaps on the brink of becoming history.

Sorrell’s departure may have been prompted by an investigation into allegations of personal misconduct, but with WPP’s share price down a third after a disastrous year, questions were already being raised about whether the 73-year-old’s vision was outdated in modern advertising.

Gerontocracies are common in medialand: Rupert Murdoch is 87; Sumner Redstone, controller of Viacom and CBS, is 94; industry titan Barry Diller is still in business at 76; and John Malone, who controls Discovery and Virgin Media owner Liberty Global, is 77. And, like Sorrell, the businesses that the ageing media barons run are all facing the same core challenge as WPP: the internet.

“I think with the departure of Sir Martin, we’re seeing the beginning of the end for a generation of media and advertising leaders and the baton being handed over to the new generation,” says David Jones, the former global chief executive of French ad group Havas, who now runs his own technology branding firm. “There’s a huge digital divide between the heads of the big legacy companies, who for the most part are well over 70 years old and grew up in a pre-internet, pre-mobile world, and the founders and heads of the tech companies, who for the most part are under 30 years old and helped invent the technology revolution we’re living through.”

For adland, the rise of social media and the power of Google and Facebook has raised valid questions from advertisers about who they spend their money with and whether big groups like WPP, France’s Publicis or US giants Omnicom and IPG still offer the best model to create and buy campaigns for them.

Procter & Gamble, the world’s biggest advertiser and owner of brands from Gillette to Pampers, says that by 2021 it will have cut more than $1.1bn (£780m) from the amount it spends with ad groups compared with 2015 levels. Marketing chief Marc Pritchard, who commands an almost $11bn annual marketing budget, has said that it is time to end the “archaic Mad Men model” and “take back control” of its advertising spending.

Scale was once the biggest selling-point of the global holding groups – providing the muscle to get big savings when buying ad slots or rolling out an international ad campaign – but now it is increasingly being seen as a costly, cumbersome achilles heel.

P&G used to work with 6,000 ad agencies around the world; it now works with 2,500 and expects to cut that number in half again. Moving more of its business inhouse will result in $2bn savings previously spent with agencies. “We have had too many people between us and the consumer,” he said recently. “We have to move a lot faster.”

The sprawling WPP empire is a case in point: it has more than 200,000 staff in 400 separate advertising and marketing businesses, working in more than 3,000 offices in 112 countries.

The stress on the holding-company model was evident last year as WPP reported its worst performance since the ad recession of 2009, the catalyst for the share price plunge. WPP underperformed its peers, but all the major ad groups are struggling with growth rates that would make a Silicon Valley upstart wince. Omnicom grew by 3%, Publicis by 0.8%, Dentsu Aegis by 0.1% and IPG by 1.6%.

Most of WPP’s rivals are also run by men much closer to the end of their career than the beginning. Omnicom’s John Wren is 65, IPG’s Michael Roth 72.

Publicis, the world’s third-largest ad group, signalled a generational change when 46-year-old Arthur Sadoun was appointed chief executive last summer. Nevertheless, his predecessor Maurice Lévy, 76, still keeps a watchful eye on the French advertising empire, having only moved as far as its powerful board.

The media landscape has been upended by the rise of technology that has enabled a new generation of digitally savvy consumers to watch what they want, when they want, on any device they want. Traditional media companies are struggling to keep pace with that change and are having to contend with the rise of Silicon Valley competitors – from Facebook to Netflix – which threaten their business models.

The Netflix streaming juggernaut shows no sign of slowing down, recently smashing analysts’ expectations to hit more than 125 million global subscribers, and the combined market value of Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook is a staggering $2.8 trillion.

A desperate need for scale and digital investment is underpinning a frenzy of consolidation in global media, to try to inject life into the ageing models of traditional players.

Rupert Murdoch’s decision to break up the global empire he spent a lifetime building – with the $66bn sale of 21st Century Fox, including Sky and the Hollywood studio behind X-Men, to Disney – is a stunning admission that, in the global war against deep-pocketed digital rivals, even he was too sub-scale to compete.

Disney’s play for Fox came at the same time as it pulled its content – From Star Wars and Pixar films to the Marvel universe and its traditional cartoons – from Netflix in the US as it races to build its own streaming service in the hope it isn’t too late to catch up.

Redstone, along with daughter Shari, is desperate to recombine CBS with Viacom to increase their chances of survival. And after being rebuffed by Murdoch in its effort to take over Fox, Comcast, owner of NBC Universal, is attempting to gatecrash Disney’s deal by mounting a £22bn bid for Fox’s crown jewel, Sky.

“I think Martin’s departure is a symptom: we are seeing pressure across the media industry,” says Peter Scott, founder of digital marketing group Be Heard. “There is a need to fight back against power of Amazon and Netflix and others that are disrupting and intruding. There is a transformation happening. A technology revolution.”

At 73, Sorrell seems fit and his indefatigable work ethic is as strong as ever, making the issue of age seemingly irrelevant, even with a new baby to deal with. The idea of retirement couldn’t have been further from his mind. “Only when they shoot me,” he had said.

Well, in the corporate sense, that is exactly what has happened. And he may be just the first casualty of a generation of leaders who are finding their ageing business models catching up with them.

Six ads that changed the world

Gibbs SR toothpaste (1955)

At 8.12pm on 22 September 1955 the UK advertising industry was changed forever when Gibbs SR toothpaste became the first ever TV commercial to be broadcast. The toothpaste brand’s place in history was purely down to luck: it won the right to be first in a lottery among 23 brands including Guinness, Surf, Lux, Batchelors Peas and Brillo pads. Initial scepticism that TV would be any good at selling products was short-lived, as the medium dominated the advertising landscape for the next five decades until internet advertising came of age.

Coca-Cola – Hilltop (1971)

Almost half a century since it was created, Hilltop remains one of the most influential and catchy TV ads in history – “I’d like to buy the world a coke and keep it company …”. It was a global phenomenon that proved that advertising was powerful enough to appropriate anything to sell a product, in this case the very anti-establishment movement of the 1960s, which would have been dead set against such commercial exploitation. “It managed to legitimise the spirit of the age and probably kill the hippy movement stone dead,” says Vicki Maguire, joint creative chief at Grey London.

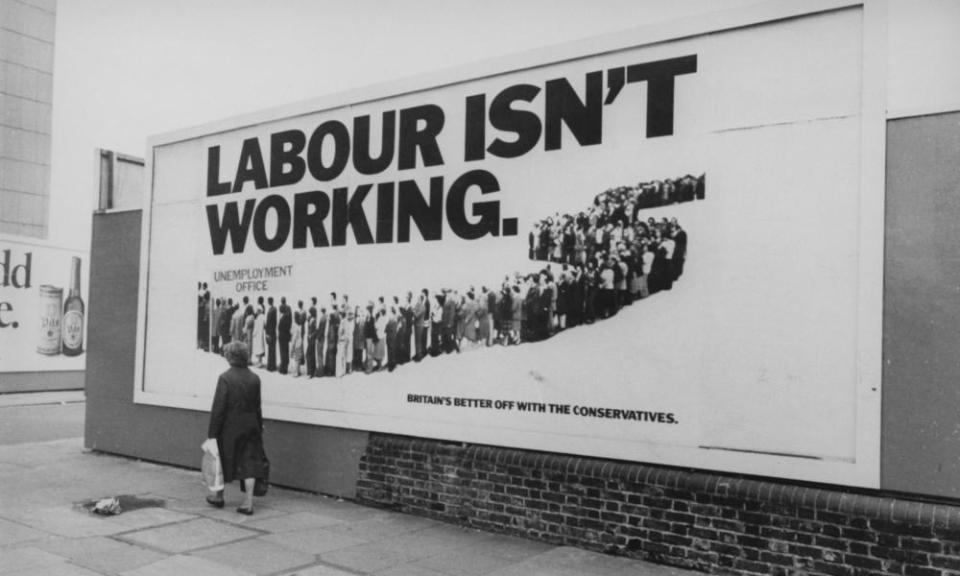

Conservative Party – Labour Isn’t Working (1979)

The Saatchi brothers’ poster for Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative party in 1979 forever changed political advertising in the UK. Before it, political ads were not a feature of UK election campaigns: they were a tactic employed in US presidential races. After it, political attack ads aiming to smear the opposition became a key part of the electioneering arsenal. It remains the most memorable and effective piece of UK political advertising of all time – Tony Blair with “demon eyes” is up there too, with Vote Leave’s slogan “take back control” now arguably joining them.

UK government – Aids campaign (1987)

The chilling TV ads featuring a falling tombstone and John Hurt’s portentous voiceover – “Don’t die of ignorance” – was an incredibly brave campaign and the world’s first major government-sponsored Aids awareness drive. Its hard-hitting tactics, and the success that followed, would be emulated by governments around the world as nations struggled to educate the public in the early days of HIV amid predictions of deaths on a massive scale. “It turned what had felt like a conveniently ‘gay problem’ into a public health issue,” said David Billing, chief creative officer at The Beyond Collective. “The nation was shocked into talking about Aids.”

Chanel No 5 – Le Film (2004)

Nicole Kidman was at the height of her Hollywood stardom, as was fellow Austalian Baz Luhrmann (Moulin Rouge, Romeo & Juliet) when the pair teamed up to make an ad that cost £18m, the most expensive ever made for TV. Kidman was paid $3.7m to play an actress pursued by paparazzi, wearing couture outfits designed by Karl Lagerfeld to the sound of Debussy. The ad marked both the zenith and the last hurrah of the Mad Men era of unbridled profligate spending: the internet era was soon to usher in phrases such as “return on investment” as the bean counters started to take control.

Dove – Campaign For Real Beauty (2004)

Dove cleverly tapped into a growing disconnection between the perfect models used in advertising and the “real” women who buy the products. The break with convention – including using normal-sized women and exposing how beauty can go from “real to retouched” in a speeded-up makeover video – has proved to be a masterclass of the new social responsibility expected from advertisers (while still making bucketloads of money for Unilever). “Those ordinary women were both inspirational and aspirational at the same time,” says Maguire. “Women who had previously spent thousands chasing the beauty myth were starting to see through the bullshit.This was timed beautifully.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News