What happens after rich kids bribe their way into college? I teach them

If you think corruption in elite US college admissions is bad, what happens once those students are in the classroom is even worse.

I know, because I teach at an elite American university – one of the oldest and best-known, which rejects about 90% of applicants each year for the small number of places it can offer to undergraduates.

In this setting, where teaching quality is at a premium and students expect faculty to give them extensive personal attention, the presence of unqualified students admitted through corrupt practices is an unmitigated disaster for education and research. While such students have long been present in the form of legacy admits, top sports recruits and the kids of multi-million-dollar donors, the latest scandal represents a new tier of Americans elbowing their way into elite universities: unqualified students from families too poor to fund new buildings, but rich enough to pay six-figure bribes to coaches and admissions advisors. This increase in the proportion of students who can’t do the work that elite universities expect of them has – at least to me and my colleagues – begun to create a palpable strain on the system, threatening the quality of education and research we are expected to deliver.

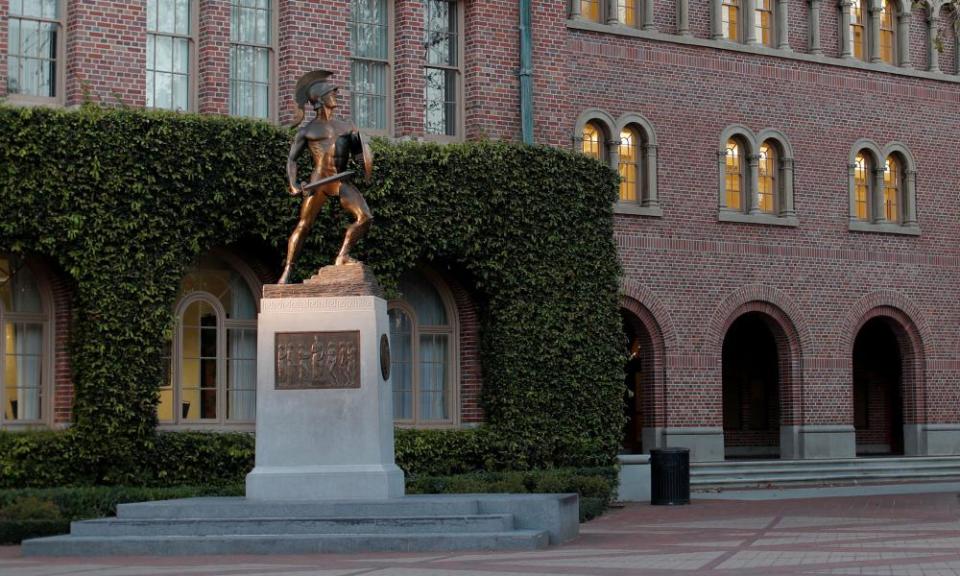

Students who can’t get into elite schools through the front door based on academic merit don’t change once they’re in class. They can’t do the work, and are generally uninterested in gaining the skills they need in order to do well. Exhibit A from the recent admissions corruption scandal is “social media celebrity” Olivia Jade Gianulli, whose parents bought her a place at the University of Southern California, and who announced last August to her huge YouTube following that “I don’t know how much of school I’m going to attend. But I do want the experience of, like, game days, partying. … I don’t really care about school.”

Every unqualified student admitted to an elite university ends up devouring hugely disproportionate amounts of faculty time and resources that rightfully belong to all the students in class. By monopolizing faculty time to help compensate for their lack of necessary academic skills, unqualified students can also derail faculty research that could benefit everyone, outside the university as well as within it. To save themselves and their careers, many of my colleagues have decided that it is no longer worth it to uphold high expectations in the classroom. “Lower your standards,” they advise new colleagues. “The fight isn’t worth it, and the administration won’t back you up if you try.”

In comparing stories, we have also found that such students strive to “work the system”, using university procedures to get the grades they desire, rather than those they have earned, and if necessary to punish faculty who refuse to accede to those demands. It is perhaps unsurprising that students whose parents circumvent the rules to get them into elite universities are often the ones who become adept at manipulating the university system in a corrupt way.

The University of Southern California was thrust into the college admissions scandal after it was revealed Olivia Jade Gianulli’s parents paid for her spot.Photograph: Mario Anzuoni/Reuters

Even for elite universities that enjoy endowments equivalent to the GDPs of small countries, there is a ruthless calculus involved in encouraging students – even the unqualified ones admitted through corrupt means – to regard themselves as customers who are always right, and faculty as service providers who serve up choice grades on demand. Students who represent money, whether in the form of their parents’ donations or athletic prowess that attracts viewers and media coverage, are simply worth more to universities as long-term sources of revenue than the faculty themselves. However well-known our names might be, most of us can easily be replaced from among the army of un- and under-employed PhDs struggling for a place in a shrinking labor market. We, not the rich students, are expendable.

For untenured faculty members, the pressures created by this setup can be a threat to their careers: it’s very difficult to teach well, let alone do the research and publishing necessary to keep your job, when you’re being hounded to provide a remedial education on top of an already heavy set of official duties.

Even for tenured professors, whose jobs are supposedly secure, becoming known as someone who won’t “play ball” by giving the sports star or the legacy an easy pass can mean exclusion from important opportunities and sources of support. So we suck it up as we recap our lectures for students who couldn’t attend due to golf team practice, or teach them skills most Americans learn in high school, or create extra credit assignments to bring up their marks.

This kind of thing has easily added 10-12 hours a week to my workload, and I know I’m not alone in that respect. As one of my colleagues put it, the unskilled and entitled students will “eat you alive”. Over the past decades as an instructor, I have seen my teaching workload increase dramatically despite holding the same number of courses in the same subjects. What has changed is the proportion of unqualified students in the classroom.

Elite American universities were never fully meritocratic. But the social benefits they produced, such as faculty contributions to knowledge and the upward mobility of first-generation college graduates, lent them legitimacy and purpose. What has been lost in the admissions corruption scandal far exceeds the handful of silver some accepted to sell out those ideals.

The author requested anonymity to protect against administrative repercussions. If you have a story or tip on this topic that you would like to share with the Guardian, contact west.coast.editors@theguardian.com.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News