Harvey Weinstein is said to have hired one – what is a prison consultant?

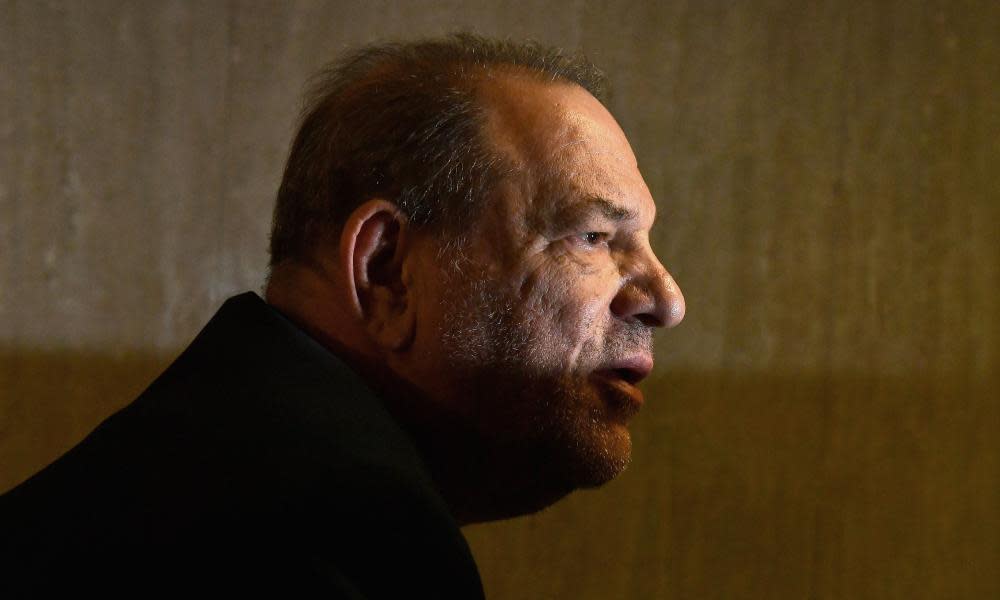

Harvey Weinstein, who was this week convicted on two sexual assault charges and faces a maximum 25-year sentence, has reportedly hired a prison consultant to make life inside a little easier. But what exactly does a prison consultant do?

Christopher Zoukis was jailed for 12 years when he was a teenager, eventually earning a bachelor’s and a master’s degree while serving his sentence. He has now written award-winning books and works with clients who have to do time in prison. We asked him what life inside might look like for Weinstein.

What service do you prove to your clients?

There are general regulations that govern almost every area of prison life, but there’s a separation between policy and its actual application. If you can apply some expertise, you can more or less make those policies work for you if there’s an issue – like a medical care, or a disciplinary issue.

Why do rich people need prison consultants?

There’s a big difference between how we live outside of prison – the social structure and norms – compared to how it works inside. White-collar guys are seen as targets, and they’re generally more gullible. But they mostly end up in minimal or low-security level prisons where there’s not a lot of prison politics or violence.

Weinstein is going the other way – and his experience will likely be dramatically different. In the political structure of a prison, people particularly dislike sex offenders and informants. Being a sex offender puts a target on your back. But because he [is] very visible , it could cause additional violence, because people can view it as an opportunity to make a name for themselves.

What’s the most common question you get asked in your line of work?

The main concern is safety. How do you greet your cellmate for the first time? How do you convey respect? In prison, respect [looks] different. If someone cuts in front of you at the store, whatever, they’re rude – but in prison, that’s seen as a direct attack upon your stature. People will deliberately disrespect you, as a hard check. They want to see if you’ll be assertive or weak. If they see you as weak, it leaves you exposed.

High-profile people need to be extremely respectful. Conflict avoidance will be a great tool, but’s a difficult line – if someone directly confronts or puts their hands on you, you have to assert yourself in a self-defense kind of way.

As soon as someone gets into prison, they need to find the guard and ask them where their cell is. A shared cell needs to be treated like someone else’s home. You knock first. If the person isn’t in, don’t go in. Go and figure out who the cellmate is – so they can meet you before they come back and find someone else “living in their house,” as it were.

Then, find someone who looks like you and ask them to show you the ropes. Copy everything they do. I know that’s not very politically correct, but neither is prison. Conduct expectations are very oriented around your group, and normally that comes down to racial lines. To even sit at a table not claimed by your group but a different group can cause all kinds of problems.

What is the difference between what we read about prison and the reality?

I was reading a quote the other day and it mentioned all these services that Weinstein will have access to. They talk about “religious services, educational services, recreational services”. In reality, educational services amounts to being allowed to get books. The religious services: we will give you a Bible. The recreational services: five days a week, we will allow you into what looks like a big dog kennel for 45 minutes – and if you’re in protective custody it might not even be safe enough to go out to the cage.

Does this line of work leave you conflicted?

It’s ironic that people go to prison for committing crimes, but inside a prison it’s so lawless. People forget that about 95% of American prisoners get out one day. I did an interview once with a host who prided himself for being tough on crime. I said to him: “Let’s say your future neighbor does 10 years in prison. Do you want him to get a college education in prison? Or do you want him to learn how to brew prison hooch really good while he’s in there?”

When you subject people to very violent and dangerous conditions, that abuse and harm comes back to our communities. Prison often isn’t about correction; it’s about control and repression. It would be nice if it fixed people rather than made them worse.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News