'It haunts your life': California's legacy of police violence against Native American women

Kelly started teaching each of her seven children about the police around the time they entered middle school and began venturing outside on their own in their hometown of San Jose, California.

“Make sure you just, ‘yes sir, no sir,’ hands where they can see them,” she’d tell them. “Don’t get smart, don’t talk back, just do the best you can to just walk away.”

That’s because Kelly, now 60-years-old and a descendant of the Tule River Tribe in California and the Mescalero Apache Tribe in New Mexico, was all too familiar with what can happen when you don’t. And sometimes, even when you do.

Related: Native American 'land taxes': a step on the roadmap for reparations

Kelly’s run-ins with police started at 17, she said, when officers caught her and a group of friends getting high at an abandoned house. Kelly, who is identified only by her first name because of the sensitive nature of her case, ran, and she remembers an officer catching up with her and grabbing her by her hair and throwing her to the ground. Then, she said, after she was handcuffed, he shoved her so hard against his car that she still has a scar where her chin was cut on the vehicle.

A few years later, when she was arrested following a separate incident, she said a police officer grabbed her breast as he was loading her into his vehicle, and then laughed about it.

But the truly traumatizing moments, she said, took place more recently, when her nephew was killed by police and a close family friend was shot and killed by an officer after he was misidentified and the phone in his hand was mistaken for a gun.

“Yes, he was involved in a horrific crime,” she said about her nephew. “Yes, I understand that. But when did the cops get to be judge and jury? He still had the right to due process.”

At a time when the US is facing a public reckoning over police violence against Black people, Kelly’s story offers a glimpse into the long-standing struggles of Native women in California with police violence.

The problem was highlighted in a report recently released by the Yurok Tribal Court and the Sovereign Bodies Institute on missing and murdered indigenous women, girls and two spirit people (MMIWG2) in California.

The report documents 165 MMIWG2 cases across the state that mostly took place within the last 40 years, though researchers believe that number is a severe undercount. A hundred and five cases took place in northern California, and for those cases where details on the circumstances of the incidents were available about 1 in 5 were victims of police brutality or lethal neglect by law enforcement officers.

There’s still so many of the legacies of that violence that we see today, and police brutality is one piece of that

Annita Lucchesi

Annita Lucchesi, a Southern Cheyenne descendant and the founding executive director of the Sovereign Bodies Institute, called the pervasiveness of police violence against Native women, girls and two spirit people in northern California “alarming”, saying it appears to stand out from the rest of the country. But, she said, it’s difficult to determine the exact scale of the problem.

Since many cases involve sexual violence or other forms of gender-based violence, women at times are hesitant to come forward, she said. “Especially for women who experience sexual violence at the hands of police, it’s probably one of the scariest things you could ever divulge,” Lucchesi said. “So unfortunately, there’s not only a lack of data, there’s a lack of structures – whether regional, local or national – that Native women feel safe reporting to.”

The report offers several first-person accounts from people reporting violent interactions with police in Humboldt county, a rural area of northern California, including a woman who said she remembers police pulling her out of her car as a high school student on several occasions. There were times, she said, officers slammed her face into the ground and then left, saying “sorry, wrong, wrong car, got a call.”

With 109 federally recognized tribes and over 70 state recognized tribes, California has more people of Native American or Alaska Native heritage than any other state in the US, according to the most recent census. There are a variety of explanations for why police violence against Native people is prevalent in the state.

One factor has to do with California being one of six states that, almost seven decades ago, was given criminal jurisdiction over tribal members. Known as Public Law 83-280 (PL 280), the legislation in California was put in place without tribal consent and means that federal law enforcement has a much smaller role in these tribal areas and state law enforcement take on the majority of cases there.

Theresa Rocha Beardall, an assistant professor at Virginia Tech, and Frank Edwards, an assistant professor at Rutgers School of Criminal Justice, have been researching PL 280 and police violence for four years, and said that on average these states see about three times higher rates of police involved killings of Native people compared with non-PL 280 states.

“The lack of consent, the immediate communication of subordination of Native people to the states created this ripe environment for conflict and I would say the propensity for grievances to turn into acts of injustice against native people,” said Beardall.

In addition, many reservations in the state have high poverty and may lack resources like cell service, clean drinking water or even electricity, which can put them at a greater risk of being taken advantage of by law enforcement, said Lucchesi.

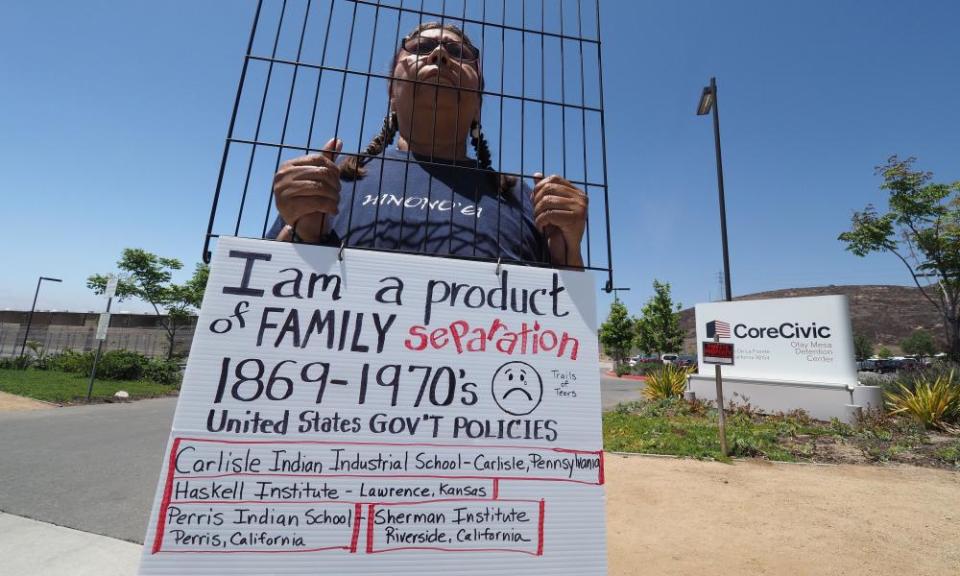

The early history of California and its brutal colonization also play a role in this violence, she said.

“There’s still so many of the legacies of that violence that we see today, and police brutality is one piece of that,” she said.

She explained that she thinks officers learned from older generations of law enforcement that they could treat the Native community as “less than” and get away with it. She said that’s something that became deeply entrenched.

Abby Abinanti, the Yurok chief justice, in northern California, explained that the Yurok word for police originally translates to “they take people.”

“That’s because when we were first introduced to them, they took our children and put them in boarding schools,” she said.

Today, Abinanti says police violence for the Yurok Tribe is a big problem, but tends to come in the form of law enforcement mishandling cases of violence against Native people.

“That increases distrust and widens the gulf between us,” she said. “And just the trickle-down effects for generations is really hard. When you lose a mother, when you lose a sister, it haunts you your entire life.”

Kelly experienced this type of violence just two years ago, when her 24-year-old granddaughter was walking home after getting a new job and was shot in the calf by a drive-by shooter. Her granddaughter called her from the scene, terrified, but when Kelly got there moments later, she said officers screamed at her and threatened to arrest her when she tried to approach and comfort her granddaughter. She remembers her granddaughter being hysterical, and saw officers scream at her as well.

“Those are the kinds of things that we live with,” she said. “Those are the kinds of things we have to try to teach our children about. It’s disappointing to say the least, and it’s scary.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News