Head injuries and sport: confusion, anger and lots of difficult questions

In all the confusion, you probably missed that the sixth International Conference on Concussion in Sport was supposed to take place this week. It was postponed a year because of the pandemic. The delay didn’t make news in the way other rearrangements did. The conference matters a lot to a few, but goes almost unnoticed by everyone else, although it is one of the more influential sports events. Every four years a group of 30-40 experts gather to review the latest research. They’re called the Concussion in Sport Group (CISG) and they summarise the findings in a document called the Consensus Statement on Concussion In Sport. You may not realise it, but if you watch or play sport then it affects you.

If your child suffered a concussion while they were playing a club game, then it’s probable they were diagnosed using a tool called the Child SCAT5, which was designed at the last conference in Berlin in 2016. If you’re a rugby fan wondering why the Italy scrum-half, Callum Braley, isn’t available to play England on Saturday or a cricket fan wondering why Cricket Australia made Steve Smith sit out Australia’s recent ODI series against England, it’s because World Rugby and the ICC follow protocols designed in accordance with the CISG consensus, which the ICC describes as “the current best benchmark practice”. CISG has done good and important work improving the protocols for how to handle head injuries.

Related: Families of Jack Charlton and Nobby Stiles back new concussion campaign

The conference is funded by the International Olympic Committee, Fifa, World Rugby and the international equestrian and ice hockey federations. And the consensus has been endorsed by 11 governing bodies and federations, including the Australian Football League, the National Ice Hockey League, the National Football League, the National Rugby League and the Football Association. In the past four years, it has been viewed more than 400,000 times and been cited in more than 1,700 academic papers. It matters.

Midway through it is the bit that, for many people, matters most. In the section “Residual effects and sequelae”, the paper lays out the Group’s consensus opinion on the long-term effects of recurrent head trauma, including cognitive impairment, depression and, crucially, the degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). You may read about CTE, have, perhaps, seen the movie, Concussion, about the man who first discovered it, Dr Bennet Omalu. The science of CTE has been a factor in multimillion-dollar class action lawsuits involving the NFL and the NHL.

Because CTE was only recently identified that science is still uncertain. There’s an awful lot we don’t know about the disease, as an editorial in The Lancet last year said: “Contrary to common perception, the clinical syndrome of CTE has not yet been fully defined. Its prevalence is unknown, and the neuropathological diagnostic criteria are no more than preliminary.”

At the same time, it’s widely accepted that there is an association between CTE and head trauma, not least because it seems that the only common factor linking the groups who suffer from CTE is exposure to head injury and head impacts.

Because the science is unclear, there is a spectrum of opinion about it. The position offered in the CISG Consensus falls at the far extreme of that spectrum. It states that: “A cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been demonstrated between CTE and Sports Related Concussions or exposure to contact sports. As such, the notion that repeated concussion or subconcussive impacts cause CTE remains unknown.” It’s a conservative position and a controversial one.

While it may have been the consensus among the panel of 36 experts at the conference in Berlin, it certainly isn’t the consensus among the wider scientific community or the athletes and families affected by the disease. Which is why so many of them have criticised it in recent articles published by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Dutch newspaper NRC, and the Guardian.

Related: Modern footballers could be at greater risk from head injury, says academic

CISG produced the consensus by pulling together all the available research on CTE published in the previous 10 years. In 2016, they found 3,819 relevant studies. But their criteria for inclusion in the consensus were so strict that only 47 of those studies were accepted. A member of CISG said they prioritise longitudinal cohort studies, which study the effects of head trauma in a group of athletes over a length of 10 years or more. That means that they don’t include “animal studies, review articles, case reports, book chapters, conference abstracts, editorials/commentaries/expert opinion, theses or dissertations”.

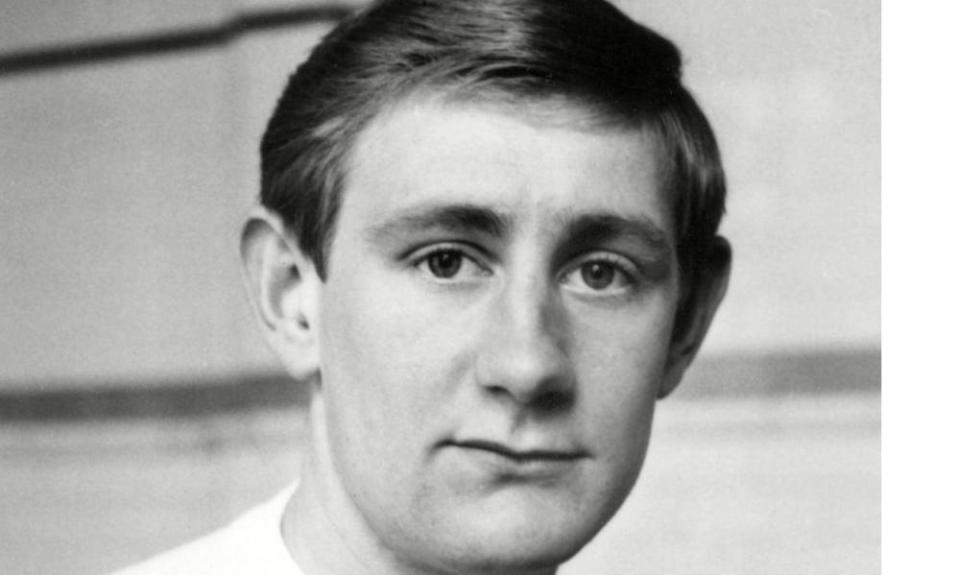

It is the case studies that are particularly problematic, not least because each of those case studies represents an athlete, and a family, who have been affected by the disease. There are academics on either side of this debate and then there are the patients caught in the middle of it. Bill Gates, the former Middlesbrough defender and now 76, has dementia and a tentative diagnosis of CTE. His wife, Judith, is one of the many people who finds herself trying to square that diagnosis with the CISG’s consensus opinion, trying, and failing, to understand the gap between CISG’s blunt denial of cause-and-effect and her husband’s experiences of the disease.

In that gap, all sorts of difficult questions arise. Questions about who gets to participate in the conference and whether the panel really reflects the breadth of opinion across the scientific and athletic communities. Questions about whether the CISG’s standard of proof is too severe, and whether the consensus would be different if it was based on more than 47 studies. Questions about whether the CISG has too much influence over the narrative surrounding the long-term consequences of concussion and whether their methods are sufficiently transparent. Questions that CISG now has another year to address.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News