Helen Frankenthaler review: A revelatory journey into a creative mind

Helen Frankenthaler was one of the great postwar abstract painters, using thinned paint in lyrical, intuitive gestures – watery stains, organic arcs and glowing blocks of colour. “Everything I make is different,” she said, “because my feelings and moods change from moment to moment, and they control the decisions in my work.” In the paintings, you feel her wrestling between control and abandon.

All of which makes her choice to make woodcuts, a discipline associated with rigid, laborious process and linear imagery – Albrecht Dürer is the ultimate woodcutter – almost perverse. Yet, as this luminous and illuminating exhibition proves, over the 40 years before her death in 2011, she created extraordinarily bold, innovative work in the medium.

We see how printmaking forces even defiantly individual artists to be collaborative in realising their vision. By showing completed prints and Frankenthaler’s many experiments, the show invites us to become absorbed in the process. And the slow, methodical journey through trial proofs and working proofs to the final print, the artist’s proof, exposes an artist’s thinking in a way you can’t often access through painting. Essence Mulberry was inspired by everything from Renaissance prints Frankenthaler saw at the Metropolitan Museum in New York to the juice of mulberries on a tree outside the master printmaker Kenneth Tyler’s studio. It ends with a gorgeous smoky red-blue plane of colour interrupted by veils and skeins of pink and brown, and a hint at the natural colour of the wood on which the work was made. Throughout, Frankenthaler uses the wood’s grain and knots as integral elements of her compositions.

It took 65 proofs to get to the final image of Essence Mulberry, and on one working proof, we see Frankenthaler’s notes. She asks her collaborators to seek a “nuance difference” she spots in the proof. “So try,” she urges, “but NO schmaltz pliz!” I love this: an artist at the heart of the creative moment, honing and tweaking.

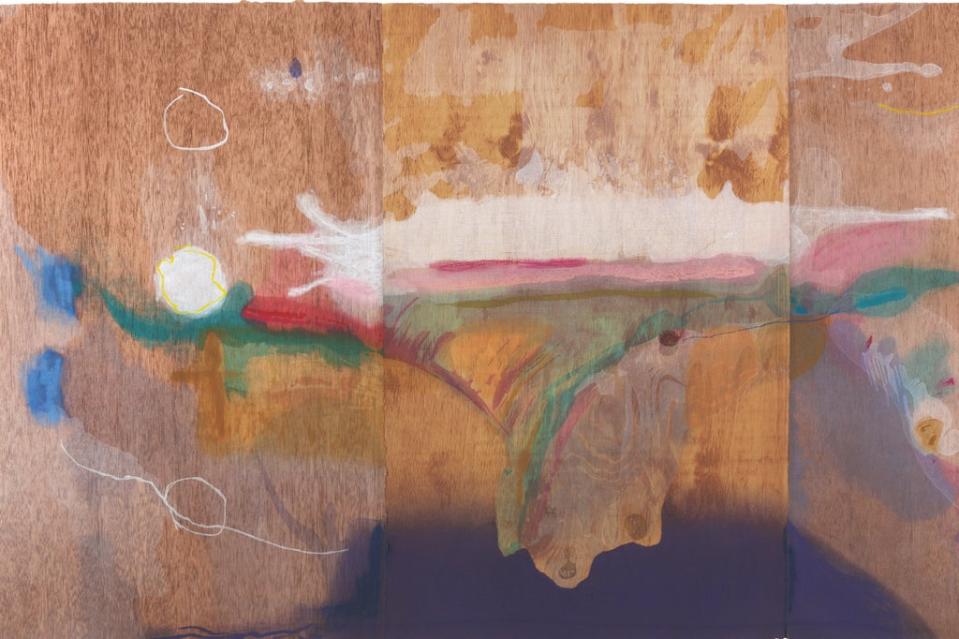

For the sequence of six woodcuts Tales of Genji, we see only the beautiful final works. As she often did, Frankenthaler created a painting that was the blueprint for Tyler and woodcut carver and printer Yasuyuki Shibata. “A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once,” she said, and that’s exactly how these works appear – vivid and spontaneous. Yet Frankenthaler worked on them with Tyler and Shibata over three years, mixing dozens of colours in each printing session, and producing more than 50 trials of each image. Ultimately, she sought “magic” in the final work.

You see this abundantly in the show’s final room, with three versions of Madame Butterfly: the original painting, a working proof with collaged paper, and the final print. Here, we see how Frankenthaler and her collaborators refined that initial image to produce a sublime final work. Just one element: a stripe of blue in the painting, made in one stroke with a half-loaded brush so that it thins in the middle, becomes, in the print, a rich, layered and textured banner of purple, red and ultramarine.

It’s this kind of detail – and there are endless examples – that makes this show a revelation.

Sept 15 - Apr 18; dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk

Read More

Meet the artists giving the British painting scene a new lease of life

A visit to the House of Dreams, the treasure trove of South London

Mixing It Up, Hayward Gallery review: Uneven but demands to be seen

Yahoo News

Yahoo News