Her Family Found Safety in the U.S. Now She's on the Frontlines Saving American Lives.

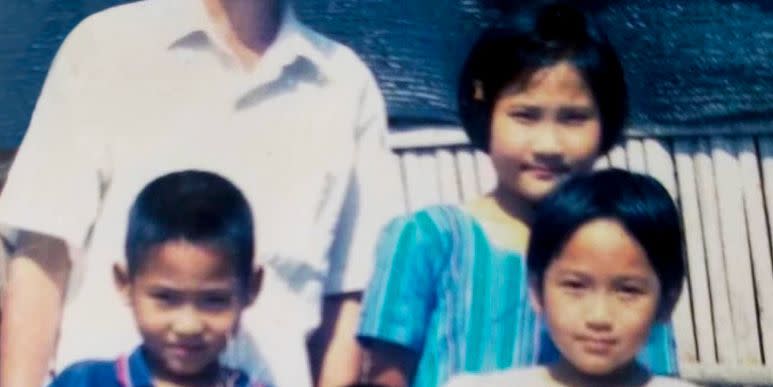

The refugee camp in Thailand where Christy Nyeing lived for seven years had no electricity, no plumbing, and no access to healthcare. Meals consisted of plain rice and the occasional chicken bone broth soup. When her mother abandoned their family, Nyeing stepped up to help raise her younger sister and two younger brothers, walking them to school and reading them bedtime stories. She cooked, gathered wood for fires, and took over cleaning duties while her father was at work. But she didn't do it alone.

"Everyone who lived in the camp came together to help out when we needed it most," Nyeing, 20, tells ELLE.com. "It is something I'll never forget."

The kindness from her community led Nyeing to pursue a career in health education when she came to the U.S. in 2011. It's also what inspired her frontline work as the country continues to battle a crippling public health crisis. Nyeing is one of 21 refugees — nearly all of who came to the U.S. through resettlement programs or are the children of resettled refugees — swabbing patients and helping with translations at a COVID-19 testing site in Georgia.

"In Thailand, I really admired how everyone helped me, even when they had so little themselves," Nyeing says. "Now I feel it is my turn to help out."

The mobile testing site where Nyeing works is organized by CORE (Community Organized Relief Effort), an emergency relief nonprofit organization offering free COVID-19 tests for high-risk communities, including low-income groups and communities of color, in coordination with International Rescue Committee. It's located in Clarkston, a small town in DeKalb county that is home to nearly 30,000 refugees from over 60 countries, including Bhutan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somali, Sudan, Liberia, and Vietnam.

The city has been dubbed the "Ellis Island of the South" because so many of its residents fled social, religious, or ethnic persecution, often with little more than the clothes on their backs. Members of the community have had to learn to navigate their new realities together. Nyeing and her family moved there in 2011.

Her parents, who are both from Myanmar, left the country to escape conflict between armed ethnic groups and the military before she was born. They applied for refugee status when Nyeing was 4 years old and settled into the refugee camp in Thailand. Her mother and father divorced three years later, leaving Nyeing to assume the role of "mom of the house," as she describes it.

"I had to help out because I'm the oldest," she says. "Sometimes I had to be very bossy!"

Before relocating to the U.S., Nyeing used to think the "American Dream" meant having a "big car, big house, and fancy news clothes," she says. "But now that I'm here, I understand it's so much more than that. It's about community and education and opportunities."

Nyeing graduated Clarkston high school last year and was accepted to Georgia State University, where she studies public health. All of her classes are online now due to the pandemic. Her siblings are still in high school, and her dad works as a cleaner in a factory.

When CORE posted a job listing for a Burmese speaker, Nyeing volunteered right away. Between classes, she puts on PPE and heads to the Clarkston site, where she translates for Myanmar refugees who need COVID tests. She helps them get registered, walks them through the nasal swab process, and explains how to access results.

The work is rewarding, she says, but it's also an opportunity to network with healthcare professionals. After college, Nyeing wants to return to Thailand and teach health classes at refugees camps like the one she grew up in.

"I'm glad I had the life that I did in Thailand, because I learned from it and now I can go back and make it better," she says. "I want to give back."

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News