Here's What Your 'Fitness Age' Can Tell You About Your Strength and Fitness

It's nearing 38°C in my garage gym, as I force out a final round of squats and AirBike intervals, trying to block out the slowly intensifying burn in my legs, lungs and, well, just about everywhere else. When the last reps are done, I’m in pieces. I sit down on the concrete floor, hyperventilating, and begin punching my legs to ease the pain. The dog tilts his head and gives me a baffled look.

I’ve been training this hard, five days a week, for as long as I can remember. Countless hours of my life have been spent in a state of exercise-induced discomfort. And I’m not exactly sure why. Men have plenty of reasons for working out. Vanity is a big one, of course. But not all of us are motivated by the promise of abs, or the ability to trounce our friends in a press-up competition.

For many, the principal motivation might best be summarised by: “Because it’s good for my health.” It will give us more and, crucially, better years on Earth. But will it? Is repeatedly taxing our bodies with reps and sets and time trials the surest route to longevity? And if not, what does training for more – and better – years look like?

Thanks to the abundance of medical papers published over the past decade,

we know that the age of a person’s heart can be different to that of, say, his kidneys or his brain. In other words, individual organs can show varying degrees of wear and tear – which is all that ageing ultimately amounts to.

But we also know that for the average man – let’s call him “you” – your lung health peaks during your mid-twenties. From the age of 30, your muscle strength starts to decrease by between 3% and 8% per decade. By 40, you’re slower on your feet. Once you hit 50, your bones start softening. From 60, it’s Murphy’s Law: what can go wrong will.

There are many competing theories about how and why we age (and die). Your telomeres, the caps on the ends of your DNA, shorten and prevent your cells from dividing; free radicals cause your cells to accumulate damage; your endocrine system loses its ability to regulate hormones. Yet I couldn’t tell you the length of my telomeres, or what free radicals have done to my body, or the efficiency of my endocrine system. It’s all far too abstract.

There might be a simpler answer to it all: fitness. “Exercise is medicine,” says Scott Trappe, director of the Human Performance Laboratory at Ball State University. “When you exercise, your muscles produce beneficial compounds that communicate with the liver, bone, heart, brain and more.” So, I set out to find my “true age”, while working to create a formula that incorporates the different metrics needed to calculate your own, too. Am I younger than the 33 candles on my next birthday cake? Or have all those hours of fitness-related discomfort been for nothing?

Restart Your Engine

Discomfort is something that exercise physiology professor Ulrik Wisløff at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology knows intimately. He specialises in cardiac fitness, specifically VO2 max, which measures the maximum amount of oxygen that your body can use during exercise.

Wisløff has measured the VO2 max of 5,000 volunteers, and his research has made him sceptical of time. Tell him about your habits and he’ll explain why your birth certificate is essentially meaningless. In 2006, he coined the term “fitness age” and created his own calculator. Go to worldfitnesslevel.org, type in some info – your age, waistline, resting pulse, exercise habits – and his algorithm spits back your true age, by comparing your stats with the data he has collected. “So, you could be 50, but if you have the fitness age of a 30-year-old, you are really 30 years old,” he says. Worryingly, the reverse is also true.

Wisløff’s “fitness age” is based on an estimation of your VO2 max, which he says “has been shown to be the single best predictor of your current and future health”. The American Heart Association agrees. It also says that cardiorespiratory fitness is a better forecaster of impending death than risk factors such as smoking, high cholesterol and type 2 diabetes.

The point at which you significantly drop your fitness age, Wisløff says, is when you are able to generate 10-12 METs, a measure of exercise intensity that stands for “metabolic equivalents of tasks”. Sleeping equals one MET. Walking at a pace of four miles per hour earns you five METs. Running at eight miles per hour scores 12 METs.

Building the fitness to hit 12 METs is where it gets tricky. Wisløff believes that the standard advice – commit to 30 minutes of moderate activity, five days a week – is flawed. “The problem is that these numbers neither account for intensity, nor reflect how your body responds to a certain activity,” he says. If you don’t truly push yourself during those 30 minutes and can’t hit 12 METs, you’re not optimally protected against disease.

To find out more, I head to the University of Nevada’s physical education complex in Las Vegas, a 13,000m2 Cold War-era research compound just a mile from the casinos of the Strip. PhD student Nathaniel Bodell is waiting for me. He stoops over a computer that’s flanked by treadmills, stationary bikes and squat racks. After some small talk, he straps a mask onto my face, asks me to stand on a treadmill and punches a few buttons that initiate a VO2 max test. The belt starts turning. “Just so you know,” says Bodell, “this won’t be the most comfortable thing you do today.”

The first four minutes are easy – the treadmill slowly ramps up from two to five miles per hour – but soon I’m running at seven and a half miles per hour. The mask clamped onto my face is calculating how many oxygen molecules I breathe in and out. The fewer oxygen molecules I exhale relative to those I inhale, the better my body is performing.

Bodell increases the incline by 2% every minute or so, making the test progressively harder. When I tap out, the treadmill has been spinning for 15 minutes and I’m running seven and a half miles per hour at a 12% incline. Bodell walks to his computer to analyse my numbers as I remove my mask and gasp for air.

“Uh, are you a runner?” he asks.

“I trail-run a day or two a week,” I say.

“It shows.”

I register a 64.9 and hit 19 METs. According to Wisløff’s estimates, my fitness level is aligned with someone younger than 20. Maybe those hideous HIIT workouts really are worth it.

While the idea that a person’s fitness age can be derived solely from their cardiac capability is intriguing, I can’t help but wonder if there are other variables to be factored in. Look at competitive endurance athletes.

Fine, their VO2 max is off the charts, but some of them look like they’re on the tail end of a hunger strike and would lose in an arm wrestle with a toddler. Surely there’s more to understanding the ageing process than what you can glean from a spell on a treadmill?

Playing the Strong Game

“Muscle is king,” says Andy Galpin, a researcher at California State University, Fullerton. “It causes, controls and regulates your ability to move. If you lose muscle quality, everything else fails quickly.” Healthy muscle controls blood-sugar levels and mitigates inflammation, which is involved in pretty much every disease that can kill you. Powerful muscles, then, may be just as important as a powerful heart.

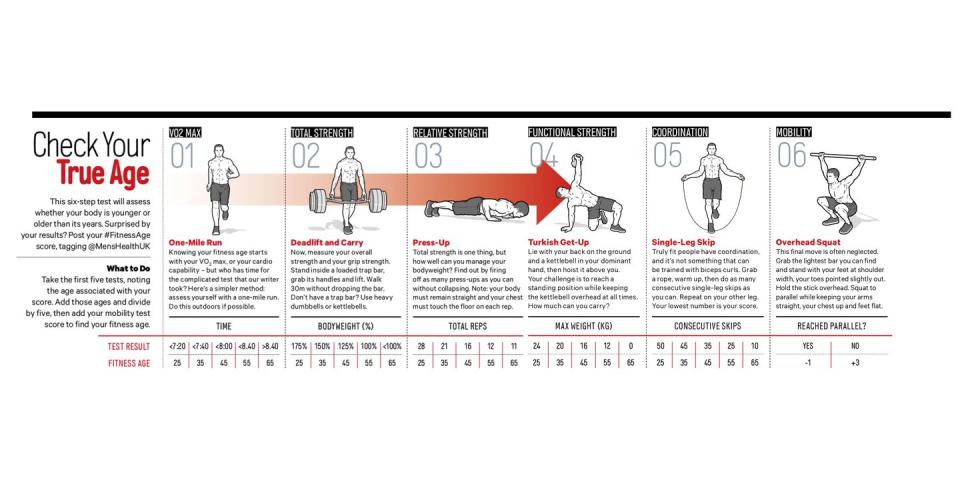

To ensure that my fitness-age formula covers all the bases, I turn to Doug Kechijian, co-founder of New York’s Resilient Performance Systems, as well as Stanford University professor Michael Fredericson. Together, they have created a protocol to score my strength in four areas.

First up: the deadlift and carry. I step inside a trap bar, which has been loaded to match my bodyweight, and grab its handles, deadlift it, then walk 30m across the floor. As well as lower-body power, this task also assesses my grip strength, a frequently overlooked factor in muscular ability. Next, I go for 135kg, 1.75 times my bodyweight. I stand inside the bar, grip it, rip it and stroll. Pass. Test number two is press-ups. I drop to the ground and bash out 40 reps. Another tick in the box.

The idea that strength is linked to mortality is further supported by a phenomenon known as the obesity paradox. According to a Mayo Clinic study, unfit, obese men with heart disease have a lower 13-year mortality risk than their normal-weight counterparts. One possible reason for this is that obese people, by necessity, generally have more muscle as a result of carrying their own weight around. (Though, of course, obesity still raises your risk of developing heart disease.)

The passage of time doesn’t just reduce your muscle mass – it also changes the composition. At the most basic level, you have type 1 and type 2 muscle fibres, and hybrids of the two. Type 1 fibres drive slower, endurance-based movements, while type 2 fibres power explosive movements. Time and inactivity shifts the balance to type 1, which is one reason why older people tend to move more slowly. The smaller your type 2 (“fast-twitch”) fibres, the “older” your muscle.

Doing only VO2 max-enhancing activities, such as running, tips the balance towards type 1. Consider the findings of a study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology. The researchers compared two identical twins with very different fitness habits; one was not a regular exerciser and the other was an endurance athlete.

As you’d expect, the endurance twin had a healthier cardiovascular system – better blood pressure, a higher VO2 max. “But he had no better strength or muscle quality,” says Galpin, who led the study. The lesson: chasing one form of exercise at the expense of all others improves some health metrics, but it weakens other crucial links in the ageing chain.

For test three, I grab a skipping rope, which I use to assess my type 2 fibres. I begin by bouncing off both feet, then transition to jumping on only my right. This tests my coordination, too. “Imagine that you trip over,” says Kechijian. “Your capacity to recover has little to do with balance and everything to do with your ability to shoot your foot or arms out to stabilise yourself.” That’s dependent on your coordination and type 2 fibres.

The final strength test is the Turkish get-up, which focuses on my ability to lift myself up from the ground. People who are unable to get up using only their legs are five times more likely to die over a six-year period, according to a study in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. I grab a 24kg kettlebell and lie on my back. The task is to get up while keeping the weight overhead throughout.

“No matter your age, you want to build a reserve of strength and muscle,” says Trappe. That becomes harder with time, but his research discovered that even 70-year-olds who lifted three times a week for 12 weeks notably improved their muscle mass. The men who stopped lifting then saw their strength decline quickly, while the ones who kept up a once-a-week routine retained their gains. Once you build a base, it just takes a little consistent effort to maintain it.

New Ways to Move

I might be a little stronger than most men of my age but, when I wake up the next morning, my back screams otherwise. I call Kelly Starrett, a physical therapist and mobility guru who works with clients ranging from Navy Seals and elite athletes to Silicon Valley CEOs. I ask him what I’m still missing. “So many people chase infinite cardio or strength capacity,” he says. “But you need just as much movement capacity. Many people go months without taking their joints through a full range of motion.”

An increasing number of experts believe that total-body mobility could be instrumental in preventing age-related degradation. Populations in Asia and the Middle East who perform many activities in the squatting position, for example, experience little to no hip and lower-back problems. In the UK, meanwhile, the NHS warns that back pain is the largest single cause of disability.

Starrett suggests a final test in my ageing assessment: an overhead squat with a broomstick. How hard could it be? I stand with my feet under my shoulders, raise the stick overhead, push my hips back and begin to descend. My goal is to lower into a full squat, with my feet flat on the floor. Things go smoothly until my thighs are parallel with the ground; I can’t go deeper without peeling my heels from the ground or tipping my torso forward.

It’s often assumed that this sort of problem is confined to much older men, but it’s not uncommon among people my age, even those who work out. Starrett says it’s probably because we see the gym as a great place to build strength and burn calories, but we’re not interested in simply moving. That’s a mistake. Research suggests that moving through full ranges of natural motion may jump-start dormant cells that fight ageing.

Your movement capacity is only as old as you’ve made it, says Katy Bowman, a physical therapist and biomechanist. Children have full command of their joints and can easily squat, lunge and lift overhead. But mobility is a use-it-or-lose-it proposition. Those kids eventually sit at school desks, then most of them will join the typical modern workforce, sitting for roughly six to eight hours a day.

When adults do move, it’s generally through limited, repetitive motions, such as walking and getting in and out of a chair, says Bowman. A standard workout of jogging, bench-pressing and curling is beneficial, to an extent, but we aren’t moving with enough variety to slow the loss of mobility. That’s my problem. I’ve built up my cardio engine at the expense of my ability to move. Movement is my weak link, the “oldest” part of my fitness.

The Fountain of Youth

Through all the research and testing, I can’t help thinking of something Starrett told me. “No system is more complex than a human being,” he said. “So many factors can predict health and longevity. We should move away from trying to find a single silver bullet.”

Believing that you have a silver bullet can cause you to miss the target on overall health. “We need to step back and ask what we’re doing exercise for,” says Galpin. “What you need for general longevity is to stimulate, challenge and stress the body internally in multiple ways. The question of what you do specifically to get there – your actual workout – it’s just noise.”

I run the numbers provided by the experts and discover that my fitness age is 28. Even with my sub-par mobility, I’ve bought my body four extra years. I still do five weekly workouts, but they’re different now. Most are no longer exercises in the art of suffering. Sure, I occasionally push the intensity; it helps to relieve stress. But it’s not a compulsion.

“All-out, all of the time”, I now realise, doesn’t give you as big a return on the effort invested as you might assume. For one session each week, I now forget the numbers on the stopwatch and barbell and focus entirely on improving my mobility. I even count a long walk with my dog as a workout, a mobile meditation that improves my health, my mind and the quality of my years.

Has my fitness slipped? Not really. Push me and I can do all the things that I could before. But those hip and back pains that used to come as a side-effect? They’re long gone.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News