Hokusai - Beyond the Great Wave, exhibition review: Turning the tide

The British Museum’s Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave celebrates the most famous figure of historic Japanese art. The show is initially underwhelming because of cramped gallery space and the necessity to be peering at rather small things. He’s one of the world’s most popular artists, so you’re unlikely ever to be there without crowds — making the going even tougher. But you’ll be quickly transported and these conditions forgotten.

Everyone knows the look of a Hokusai: woodblock prints where a few simple colours in different tonal variations are related so ingeniously that the impression is that there’s much more than there really is. The interest is in two aspects, made equally as important as the other: the window he opened onto a society 200 years ago and his fantastically inventive technical approaches.

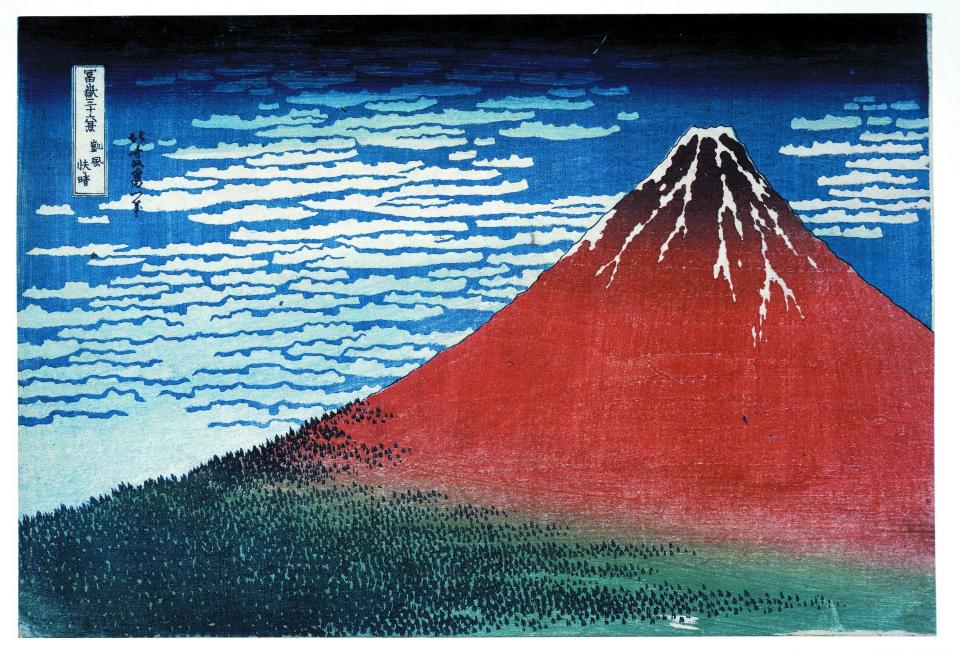

The imagery is entrancing: Mount Fuji, near Tokyo, glowing red against blue skies; great sea waves in a storm overwhelming fishing boats; and men in pigtails touring handsome waterfalls. And so are the means by which it is conveyed, which are always sharply noticeable. Van Gogh said everything he’d done was influenced by Japanese art, and in Van Gogh’s short career, spanning hardly much more than the 1880s, Hokusai, who died in 1849, was the Japanese name everyone knew.

Japan was isolated for two centuries but trade was opened up ten years after his death, and it was as trade objects rather than high art that his prints and illustrations first arrived in Europe. His style — flat, light and patterned, picturing people and nature as well as monsters and mythic beings — was immediately popular in the West. In France it was transmitted everywhere in admiring, if oversweet, imitations on plates, screens, fans and vases. This popular design style was known as “Japonisme”.

But it also transferred to fine artists looking for a way out of academicism, and from the 1860s onwards it was one of the most powerful factors in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. From Manet and Monet to Van Gogh, modern artists valued that double aspect of, on the one hand, a broad, eye-catching composition, so visually fresh it has a life of its own and, on the other, the surfaces, shapes and textures we see every day, which the composition contains and arranges.

Curiously, Hokusai gave himself dozens of different names over the years. He was 39 when he adopted “Hokusai”, which means “north studio”. The show covers a period when he no longer used it, having given it away to a pupil. In 1820, at the age of 61, he started using the name Litsu, meaning “another year” or “fresh beginning”. He had 30 years to go. (His last self-given name translates as “old man crazy to paint”,)

The show begins in his Litsu period. It might seem odd to focus on late work alone. We get to know about the whole of his life story in a gripping narrative supplied in chunks on explanatory wall labels: the name-changes, constant travel to complete commissioned work, the shabby conditions he preferred to work in, his complicated family affairs. But it is in fact perfectly appropriate that we see only the output of the last 30 years. It was the time in which everything he’s now known for first appeared.

Mount Fuji is forever associated with him because of a life-saving commission he received in 1830. He produced 36 Views of Mount Fuji over a period of two years and made enough money to begin to recover from a series of disasters. He had suffered a stroke and had to cure its effects on his own with a home remedy because he couldn’t afford a doctor. A grandson ran up huge debts, which Hokusai ended up having to pay. And on top of everything, his wife died.

One of the series, Fine Wind Clear Morning, shows Fuji in beautifully vibrating red and green tones against a vivid blue sky. Thin strips of bright white cloud break up the blue and visually rhyme with crackling white lines, like veins, at the top of the mountain. The latter suggest the mountain’s volcanic nature — it last erupted 50 years before Hokusai’s birth — and also the fact that the peak is snow-capped for several months every year.

The picture from the 36 Views probably known to most people today is correctly titled Under a Wave off Kanagawa, but its popular name is The Great Wave. It is pretty small considering its impact, barely 15 inches across. In the distance is the mountain, dwarfed in scale by the waves, which tower like mountains themselves over trapped fishing boats. The sheer stylish minimalism of the design is as exciting as the narrative meaning, rich with symbolism — permanent mountain, ephemeral life, awesome nature.

You’re seeing a great drama in which complex information is intensely distilled. The only colours are light and dark blue plus white — the white is unmarked paper — and a graded grey. The lightest grey is still dramatically darker than the white. The drawing of the waves is based on rolling curves with slightly bumpy contours, with sea foam represented by clusters of hook-like shapes.

The boats are hardly registered at first. They gradually appear: long sleek forms, like geometric slivers that comment visually on the shapes made by the deep valleys of the waves. The terrified sailors are tiny: helpless white blips hardly different in form and scale to the dots standing for snow or spots of sea foam. Van Gogh was fascinated by the image. He wrote to his brother: “These waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it.”

Hokusai believed every year of working improved his ability and he would have to get to 100 before he really hit the peak. At 75 he wrote modestly and with comic particularity that it was only in his 73rd year that “I was somewhat able to fathom the structure of birds, animals, insects and fish.” It’s not just Buddhist traditions that call for all things animate and inanimate to be regarded as interconnected. Any art focused on reality calls for it too. But Hokusai was peculiarly able to make the familiar striking so the world is re-seen, in a way that had a profound effect on the course of art history.

Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave is at the British Museum, WC1 from Thursday until August 13; britishmuseum.org

Yahoo News

Yahoo News