Holland's Trudeau? Youthful Green surges before vote in campaign dominated by right

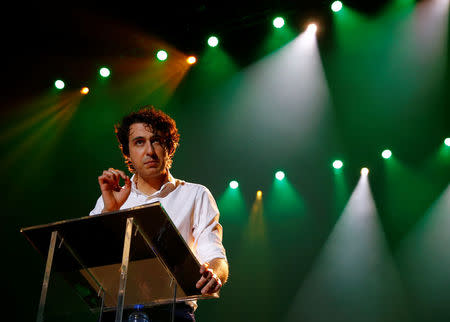

((This version of the March 10 story removes reference to crowd having paid to attend party rally in paragraph 7. Admission to the event was free.)) By Anthony Deutsch AMSTERDAM (Reuters) - A boyish 30-year-old who looks like Justin Trudeau and sounds like Barack Obama has emerged as a potential kingmaker in Dutch politics, riding a rare message of tolerance ahead of an election dominated by anti-immigrant rhetoric. Jesse Klaver, son of a Moroccan father and part Indonesian mother, is expected to turn his tiny Green Left party into one of the main groups in the Dutch parliament in a vote next week that has mostly made headlines because of a far right surge. The election is mainly billed as a challenge by flamboyant anti-Islam nationalist Geert Wilders to conservative Prime Minister Mark Rutte, who has responded by campaigning on proposals for measures to curb immigration. It is the first big vote in Europe in a year that will also see elections in France and Germany, where the far right is forecast to win its best showings since World War Two. But with half of Dutch voters still undecided and no party expected to come close to a majority, Klaver has filled a void by speaking for those who yearn for a more inclusive message. He has built up a strong following on social media and through small "meet up" events that began when he took over the party leadership in May of 2015. Gatherings in living rooms grew to fill 100-seat theatres. This week he held the largest political rally of the entire Dutch election campaign, drawing a crowd of more than 5,000 to a packed Amsterdam concert hall. Five thousand more watched live on Facebook. The youngest party leader in Dutch history, his dark curls and boyish looks give him an unmistakable resemblance to Trudeau, the Canadian premier known for welcoming refugees. Supporters have co-opted a slogan from former U.S. president Obama, helped by the fact that Klaver's first name is pronounced in Dutch almost exactly like the English word "yes". "Jesse we can!" supporters posted during the live online feed of the rally as a tie-less and confident Klaver told a cheering crowd that Dutch voters have a chance to stop Europe's drift towards the far right. "This year is not only about the election in the Netherlands, but elections in the whole of Europe," he said. "In the Netherlands, we have to show that populism can be stopped and there is an alternative. That alternative is us." Dutch politics are fractious - there are 11 political parties in the 150-seat parliament now, most of them tiny, and eight independents. But Klaver's success could turn the Left Greens into one of the handful of parties big enough to win a place in the ruling coalition, especially if mainstream parties link up to keep out Wilders, convicted last year of fomenting racial hatred. Polls show Klaver's Left Greens on course to quadruple their representation to 16 seats, while Rutte's centre-right liberals shrink from 41 to somewhere around 25, not far ahead of Wilders' nationalists. For most Dutch, openness and tolerance are fundamental national traits of their small seafaring country. Holland has been a European haven for refugees since the 16th Century, when the mainly Protestant Dutch broke away from Catholic Spain, committed their new state to religious freedom and offered protection to persecuted minorities such as Spanish Jews. Wilders argues that precisely that tolerance is threatened by Muslims, who he says practice a "totalitarian" faith. Muslims make up 5 percent of the Dutch population. In a live television debate watched by 1.6 million viewers, Klaver shot back that right-wing populism, not immigration, is undercutting Dutch traditions. "The values the Netherlands stands for, for many, many decades, centuries actually, its freedom, its tolerance, its empathy. ..they are destroying it," he told Reuters in an interview. Klaver said that if elected, he would increase spending on renewable energy and address social problems that have led 40 percent of Moroccan and Turkish immigrants to feel unwelcome. "It's terrible when people are born in the Netherlands have the feeling they are not part of this society and it is not something to be proud of, but something to be ashamed of. And I want to change that. "This is a change of hope, not of fear," he said. (Reporting by Anthony Deutsch; editing by Peter Graff)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News