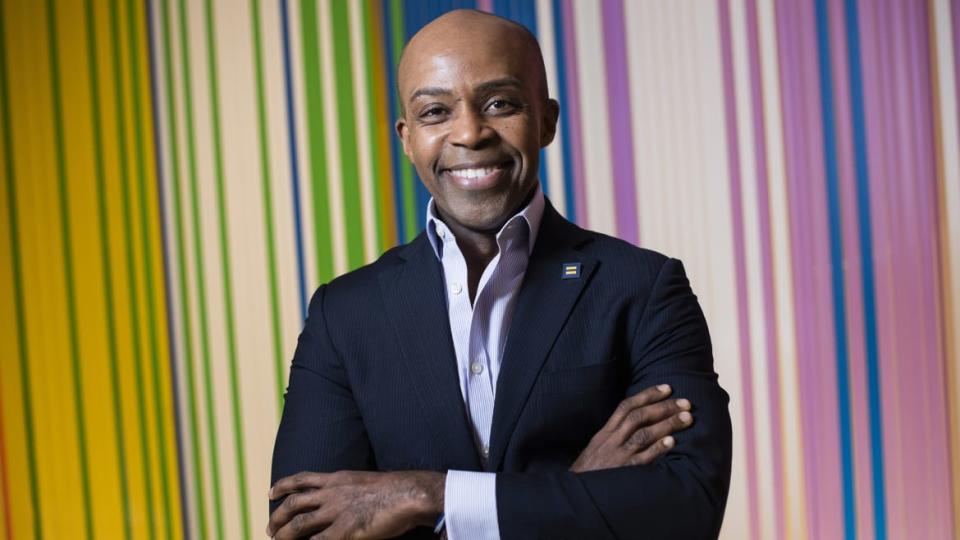

HRC President Alphonso David on Racism, LGBTQ Equality, and Why Celebrities Need to Speak Up

Alphonso David remembers running and then looking back at his family home to see a “sea of orange”: machine gun fire.

It was 1980. His father was the first elected mayor of Monrovia in Liberia. On that day a coup d’état had begun. Soldiers had come to his family’s house. His father had scooped the then 10-year-old Alphonso up in his arms and thrown him to safety from their bathroom window.

“I heard gunshots at the front door,” David recalled. “But as a child that didn’t make any sense to me. As I ran away from the house I looked back. They were shooting at our beds because they thought we were still asleep. When my father threw me from that window, we had no idea what was going on.”

His father, who moments before had saved his son’s life, was gone. When he reappeared after being incarcerated, 18 months later, Alphonso thought he was an impostor—and that his real father was dead.

New York’s 50th LGBTQ Pride March Should Be as Political as Possible

David, the first black president of the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) in its 40-year history, recalls the dramatic events of his childhood as foundational in his adult life and work as a civil rights attorney, and now the head of the nation’s largest and most powerful LGBTQ advocacy organization. He says his commitment to fighting injustice and for the marginalized is rooted in his tumultuous childhood.

Speaking at the start of Pride month, as the nation roils from the ongoing aftershocks of George Floyd’s death, David said it was a “bizarre time to be living, and an opportunity to really effect change. Here’s hoping.” David, who was appointed as HRC’s chief last June, is, as one might expect from a civil rights lawyer, an optimistic realist—or maybe a realistic optimist.

To oversee HRC in the Trump era, and in a critical election year, requires both acknowledging the grit of reality—the prejudice, particularly aimed at trans people, and legislative attacks on LGBTQ people—and the necessity of optimism, lobbying for new, pro-equality political leadership, mobilizing LGBTQ voters and their allies, and hoping (perhaps against hope) that the Supreme Court rules that people cannot be fired simply because of their sexual orientation and gender identity.

David, 49, said the impact of recent events has ensured that “certain images and sounds have been on a virtual loop in my head: Amy Cooper’s voice in Central Park, George Floyd’s voice in Minneapolis, and protesters screaming, running from the White House, after that [President Donald Trump’s] ridiculous display of cowardice that we saw in the Rose Garden. Those voices are a continuous loop in my head, reminding me of the challenges people of color, specifically black people, face in the country.”

The scale and volume of the protests following Floyd’s death have also been “heartening” for David—it seems people, he says, are finally realizing “the reality of oppression that black people have been living under for such a long time. I appreciate that people are finally listening, and I am disturbed by the images and sounds that it took to get us here.”

The deaths of Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade mark a cultural turning point, said David, although “what the ultimate impact will be is anyone’s guess.” Perhaps the impact is greater this time, the awareness heightened, with most people sequestered at home because of COVID-19.

“No marginalized group in this country has ever achieved true liberation, so we have been collectively fighting to make sure marginalized groups are respected and treated the same under our Constitution, which arguably should be functioning in a race and ethnicity-neutral way, and it hasn’t been,” said David. “Trump is implementing rules and regulations in a very different way that applies to marginalized groups than non-marginalized groups.”

David hopes to be instrumental in taking the feeling of the moment and shaping it into “meaningful solutions” that transform the status quo, “whether that is making sure we have people of color serving as police chiefs and making sure we have real criminal justice reform, to making sure we have the Equality Act which would prohibit discrimination against LGBTQ people; to making sure we have someone in the White House who respects all people regardless of the color of their skin, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

Changes in the law are important, David said, but he is more focused on getting people generally “invested in the struggle for equality.”

David said it was a “very good and difficult question to answer” about whether he thought that the Supreme Court would rule that Title VII protected LGBTQ people from discrimination. “It challenges me from the purely emotional space from which I think, and from the purely legal perspective as I have been trained.” He hopes that the justices observe the “20 years of case law” that supports the principle of equality.

“I am hopeful that we will receive a positive legal ruling,” David said. But whatever SCOTUS rules, David remains committed to fighting for the passage of the Equality Act, which would ensure LGBTQ people are protected under federal law.

The act has passed Congress but will never pass in a Republican-controlled Senate or likely get signed by President Trump. To that end, HRC has endorsed 45 candidates, including five would-be senators, as well as focusing its 2020 campaign efforts and voter mobilization on seven priority states: Arizona, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wisconsin.

This reporter asked if David believed that Trump was genuinely anti-LGBTQ or acting transactionally to shore up his right-wing voter base.

“I believe there is something psychologically wrong with Donald Trump,” said David. “I think his faculties have been impaired. He is driven by opportunity and by bias. He doesn’t have a moral compass. Without a moral compass, it does not matter who is trampled on to seize the opportunity he is seeking. The opportunity is power, and the goal is to seize and hold on to power and use it for personal gain.”

David observes that Trump has “flouted the rule of law time and again” and “sought to corrupt” democracy in his quest to hold on to power. “That unfortunately is the man we have sitting in the White House.” The police targeting protesters so Trump could have his photo opportunity “is so deeply offensive and discriminatory and inconsistent to the principles of the Constitution that it boggles the mind he is even in the White House.”

Out-going Human Rights Campaign president Chad Griffin (L) and Alphonso David march in the New York City Pride March, 2019.

David would like LGBTQ celebrities and politicians to take a more proactive stance in the run-up the election.

“I think more needs to be said and done. We’re still fighting for basic necessities and basic human rights. In 29 states in this country, LGBTQ people are not protected by state laws. They can be fired from their jobs, denied housing, and denied access to public accommodations. If we had every person who is supportive theoretically of LGBTQ issues actively engage we can change the political and social landscape so that LGBTQ people are protected moving forward. I don’t think we have enough people engaged in this fight.”

David said well-known LGBTQ people and other famous allies should “support organizations like HRC doing work on the ground; get officials elected into office; engage and mobilize your personal networks; make sure they vote and understand the importance of voting; and use your personal platforms to raise visibility and awareness on LGBTQ issues and issues affecting marginalized communities.”

The attacks on trans people remind David of when bigots tried to derail same-sex marriage. LGB people “must stand together” with trans people in the face of such attacks, he said. David noted that one of the cases before the Supreme Court is of trans woman Aimee Stephens, who recently died before hearing SCOTUS’ ruling.

David recalled experiencing racism as a younger man when he went on a cross-country road trip. In West Virginia, he and his Italian-American friend stopped for gas in West Virginia. David went in and asked the female clerk for $20 worth of gas, and she did not respond to him.

He suspected at first she might have a disability that prevented her from acknowledging him. After repeating himself, he returned to the car. His buddy went in, “and within two seconds got gas.” David said, “That is the experience of so many people of color in this country, and I have experienced many others.”

The death of George Floyd, and all that has flowed from it, has also coincided with Pride month. Ernest Owens, writing in The Daily Beast this week, pointed to the need to tackle racism within the LGBTQ community.

“There is a lot of work to be done,” David agreed. “I am the first person of color to lead our largest LGBTQ civil rights organization—in 2020. There is a lot of bias and prejudice and racism within the LGBTQ community. There were 26 trans women of color murdered last year. There are 12 trans people, many of them people of color, who have been killed this year. We have some members of the community who flaunt their bias and prejudices in a variety of different ways, from the social context to the professional context. There is a lot of work to be done within the LGBTQ community in terms of the awareness of people.”

Within the LGBTQ community, David said, “we find people who with no shame will say, ‘I don’t find black people attractive.’ It is one thing to say you are not attracted to certain types of people, but to say an entire race is unattractive, an entire class of people is unattractive, says a lot about how we view race and ethnicity, and why I think we have a lot of work to do.”

David revealed he had been carded in gay bars, while those around him who are not white have not been. He has had his bag checked when other white customers have not. Such markers of prejudice “happen in almost every type of interaction,” said David.

This reporter asked if he felt he had been sexually objectified by white men. “Unfortunately, I think many black men have,” said David. “There is an objectification that certainly exists within the community and I have been subject to it. There is an interesting phrase that some black men have, which is ‘You’re willing to have sex with me, but you’re not willing to date me.’ Many men of color who have interracial relationships have had these experiences, many have not. I don’t want to make it seem there is some monolithic approach that white men have when they engage in relationships with black men, but it exists in the community.”

David said he was not familiar with Grindr, the app that this week announced it was removing the feature that allowed users to filter potential mates according to race and ethnicity. However, he welcomed the move as a step forward, having seen white people post “no black people.” He wondered if people felt so comfortable “excusing an entire group of people based on who they are, does it stay within that application or seep out” in other ways, into other contexts.

Echoing a speech he gave last September, David said, “We have to come to a place where we see beyond ourselves and others who don’t look like us. It is important from an advocacy perspective as we fight to remove the vestiges of discrimination that have shackled LGBTQ people of color. If the wider community will stand up in support of changing discriminatory laws and practices, we may be able to create a pathway to equality. But the pathway has to be sustainable.”

“I thought my father was not real, that he was dead”

David was born in Silver Spring, Maryland. At a year old, he and his parents moved to Liberia, where his father was the first elected mayor of the capital, Monrovia, and where his uncle, William Tolbert, was the president of the country.

“I lived a very privileged life for 10 years,” David, a passionate roller-skater as a kid, said. “The remaining three there was a military coup.”

During that coup in 1980, David’s uncle was assassinated, his father was jailed for 18 months, and the family was placed under house arrest.

“During that time for me, a 10-year-old child, I saw things that I wouldn’t wish on any child,” said David. “I have seen the heads blown off people, people murdered, women raped. It’s a stark reminder of how important it is for us to protect our democracy because I’ve seen in other countries people losing their democracy. I fear we are going closer and closer to authoritarian rule with Donald Trump, and we have to invest in this election to make sure we protect our democracy that is at stake.”

David said he was “a very precocious, inquisitive child. I wanted to know everything. And I was more interested in watching than participating.” He read a lot of books and watched a lot of human behavior. He thought he would be a surgeon; his family planned for him to go to Oxford University, study medicine, then return to Liberia to practice medicine.

House arrest changed that. The young David became interested instead in the law, and who decreed it. “Losing our democracy and living under a dictatorship informed my passion for representing the disenfranchised and marginalized, and people who have been oppressed. That’s why I do what I do.”

“When they arrested my father and took him away, I thought it would be the last time I would see him,” recalled David. “Over the next 18 months the rebels televised their executions. They would execute men on the beach, tied to wooden poles. The camera would go from one person to the next. We watched those executions in horror, because we assumed the next face we would see would be our father. I never thought I would see him again. When I did see him again, I didn’t think he was real. I thought he was an impostor. I thought they had sent someone to try to infiltrate our family. I thought he was not real, that he was dead.”

David recalled that 18 months after his arrest, his father reappeared. His son was now about 13. “When I saw him again, he came into the room, his beard down to his belly. He looked like someone from a horror movie. I thought, ‘That’s not him.’ He said he wanted me to welcome him. But I ran away from him, I didn’t think he was real. I thought he was someone else.”

As a child, said David, “you have to think about the impact that has on your psyche and personal relationships because you have to rebuild them as if they didn’t exist. You are operating from a place of distrust and fear, and you think about how to build a familial relationship with someone you should be very, very close to. It took a number of years for us to rebuild that level of comfort and trust.”

This reporter asked David how his father convinced David he was actually his father.

“I watched him for months, to see whether or not he picked up a spoon in the same way as my father picked up a spoon, whether he walked the same way. After a while, I don’t know what it was but I thought, ‘OK, yeah it’s him.’”

How traumatizing was all this? “It affected me definitely. It affected personally how I view the world, and why I feel it is important for us to live our lives and make sure people can live their lives openly. If you don’t have freedom and equality, you can’t really live. If you are fearful to walk down the street, you can’t really live. All of that’s based on my own experiences.”

The family returned to America in the early 1980s, initially planning to live in New York City but ultimately returning to Maryland and the city of Baltimore.

“It took us a long time to acclimate,” David recalled. His schooling (private to public), curriculum, and teaching all changed. “I went from a largely all-black school to an integrated school where everyone thought I had a tail because I was from Africa,” David said. He was unaware of the level of ignorance and “lack of awareness and misconceptions” Americans had about Africa. “People thought Africa was a country, not a continent, and that North America was larger than Africa.”

Did he face racism? “Yes. A lot of racism. I got it from all angles. Children thought I had a tail. ‘Did you live with baboons and tigers?’ The children saw me as an object, not a potential friend. I was the outside, the other, the baboon, the kid who would eat lunch alone in some cases because I was the kid from Africa, and there was no value attached to it.”

This remained so through middle and high school. “Something changed in college, where there was a cultural shift of musicians embracing their heritage. It was the age of A Tribe Called Quest and Queen Latifah—artists who talked about the importance of going back to their roots. It shifted in a very interesting and somewhat cosmetic way for me, where it became kids getting to know me because I was from Africa. ‘This is my friend from Africa.’ It was a fascinating journey in both reality and psychology.”

David’s coming to awareness of his sexuality, and his coming out, was just as complex. He laughed as he began the tale. “So, I had this interesting theory. I thought, as a child, I found boys attractive, not necessarily in the same way as girls. I thought all other boys felt the same way but were not allowed to say anything because it was not accepted. For a long time I thought every other boy felt the same way. It was not till middle or high school I realized, ‘No, you’re really different from other kids.’” He first dated another guy at college and came out to his family after college, “which was a potent and traumatic experience,” he said.

David assumed his family would disown him after he told them. “My father had said at the dinner table at some point that ‘If any of my children are gay, I will disown them.’ I never forgot that. I put myself through college recognizing I would always have to take care of myself because at some point someone would find out the secret that I had. Indeed, he followed through with his promise and disowned me, and I had no connection with my family. In my culture ‘disowning’ means you lose your inheritance, you can’t use the family’s last name and have any contact with them.”

This reporter asked David how that experience felt.

“It was insane. It was really insane, for me. I had prepared to the extent you can prepare for this, for the possibility of being alienated from your family, but when it actually happened it was a traumatic experience for me. My parents wanted me to see a pastor and a psychiatrist. They wanted me to effectively go through conversion therapy.”

What did David do?

“None of the above. I told them I was not willing to see a psychiatrist and that I had already seen therapist, at which my father said, ‘There we go, he made you gay.’ My mother wanted me to see a pastor and I said, ‘No. This is not something I’m going to change. I’ve wrestled with it for a long time. This is who I am, and I completely understand if you’re not comfortable with it, but we will have to live at this impasse.’ It took them a while to get to the point where they accepted that it was something I couldn’t change, and they slowly came back into the fold… It took years for my father to get to the point of—I don’t want to say he accepted my sexual orientation, but he at least accepted I couldn’t change it.”

The process of bridges being rebuilt was “somewhat organic” and unfolded over a year. David had remained close to his two sisters and brothers, who reached out to him to support him.

His parents eventually said, “OK, fine, this is who you are, but you’re not allowed to tell anyone.” Too late: David had already told his siblings and some cousins. He recalled he had started dating someone and was invited to a wedding. He told his mother he was happy to attend, as long as his then-partner was with him. His mother told him no, and so David did not attend the wedding.

“It was a gradual, difficult exercise and experience for them, and I think for some parents if a child comes out as LGBTQ, it’s very different if that child shows up with someone they are dating because that is a manifestation of sexual orientation and gender identity that’s very difficult to ignore.”

Both his parents have now passed away (David has inherited his father’s collection of jazz records; he himself is now a huge fan). His father moved back to Liberia and died there.

The “last meaningful contact” David had with him was after he graduated from law school and his father said he was “the next Oliver Wendell Holmes,” David recalled. “He was so incredibly proud of my graduating from law school and what I was planning on doing at the time—going to clerk for a federal judge [Clifford Scott Green] and then work at a major law firm [Blank Rome LLP in Philadelphia]. Before he passed away, he took comfort and pride in the extent of my professional accomplishments.” The men were on good terms when his father died.

David’s mother, diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, died in America. His relationship with her was “great. My mother loved and cared for me deeply. It was her faith and her religion and interpretation of scripture by some leaders that led her to deeply worry about me living openly as gay man and what would happen to me. My relationship was very good with her when she passed away.”

David hopes his parents would “appreciate the value and importance” of his role at HRC “and the impact I am seeking to have.” His siblings and living family members are “incredibly proud and supportive.”

One reason, as HRC chief, David is keen to build bridges with faith communities is because he sees both institutions as fighting for justice and equality. “Unfortunately scripture has been interpreted for decades to suppress and oppress marginalize people. For years scripture was used to support slavery and exclude black people from basic needs and necessities, and scripture has been used to discriminate against LGBTQ people.”

His mother found a way “to live in the world where she honored her faith and at the same time maintained communication with me.” David believes there is a “generational shift” where younger people see how religion has been used to oppress others, “while we still have more work to do with older people to show that LGBTQ people do not threaten their faith.”

While the Trump administration and some groups have found “religious liberty” to be a new anti-LGBTQ rallying call, David does not see this as an effective long-term strategy. As for his own beliefs, David says he believes in “a higher power” and is a “person of faith and very spiritual.”

“Take this opportunity to take a step back and reconnect to our history, and the reasons why we celebrate Pride”

David said working at a commercial law firm was “incredible training, but not my passion.” He became a staff attorney at LGBTQ advocacy organization Lambda Legal. He quotes Mark Twain: “The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why.”

“For me, litigation is interesting but not why I am on this planet, not why am here. I am here to advance the interest of marginalized communities, and effect change and advance civil rights.”

David spent a number of years as New York state’s deputy secretary and counsel for civil rights, and then alongside Gov. Andrew Cuomo as counsel to the governor. He has also been a law professor at Fordham University Law School. He is cagey on whether he desires a future career in politics. “I don’t know what the future holds. I certainly enjoyed working for Gov. Cuomo,” David said.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Glennda Testone, Charles King, and Alphonso David attend a press conference to announce the blueprint to end AIDS in New York on April 29, 2015.

He is most proud of writing New York state’s landmark marriage equality legislation in 2011, and work around criminal justice reform and advancing legislation on paid family leave. He is, however, “100 percent focused” on his current role and “transforming the landscape for LGBTQ people and other marginalized groups.” So, a mayoralty, governorship, senator, congressman—what’s his future desire? “They all have pros and cons,” said David, proving his politician’s skill for easy deflection. “It sort of depends on what you want to achieve.”

As someone who was close to Cuomo, just what is the beef between him and Mayor Bill de Blasio?

“Haha, that is a question I am not going to answer because I don’t know. They’ve known each other for a very long time. I think they understand each other and to some degree disagree on policy solutions. I don’t know what the ultimate issue could be. I think they agree to disagree when they have to, and agree when they can. It is a relationship that they have and it is complicated. Ultimately, I go back to: two strong-minded individuals who have opinions and perspectives, and sometimes those perspectives and opinions clash.”

David will turn 50 on Aug. 13. “I am a Leo, I’m a lion,” he laughed. Is it a landmark for him? “I am one of those people who assigns value to numbers,” he said. “I think that it gives me the opportunity to take step back to see what I’ve done with my time on earth,” as well as looking at his goals and seeing if any need to be redefined.

David said that love is “very important” to him. He is currently single, having been in a relationship for several years. He is happy being single, he said, but if he met “the right person” would be open to exploring a relationship.

This is an odd Pride month (its 50th anniversary being marked in New York City), with nearly all marches canceled and with the different aftershocks of George Floyd’s death and coronavirus roiling communities.

David recommends LGBTQ people “take this opportunity to take a step back and reconnect to our history and the reasons why we celebrate Pride. Pride started in protest, when LGBTQ people had enough and fought back, because we had been oppressed and targeted for such a long time. It ultimately culminated at Stonewall. Understand the oppression LGBTQ people faced in the past, and realign ourselves with those who are facing hardship today, and recommit to equality for all people.”

This reporter asked who David’s LGBTQ touchstone was. “James Baldwin, James Baldwin, James Baldwin,” he said three times.

David recalled reading Conversations with James Baldwin, which captured “his true essence as a person and what drove him. It resonated with me.” David also recommended several films about Baldwin, like the “incredible” The Price of the Ticket and I Am Not Your Negro (based on Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript, Remember This House).

There are many other LGBTQ figures who have inspired him, David said. “But, for me, James Baldwin is a central figure in speaking up and fighting back against oppression, and he did it so eloquently and so forcefully. His prose, his language, his posture on civil rights issues, has transcended time and space, and what he wrote about in the 1960s still remains true today. For me, he is the figure to look to and think about as we go through this time.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News