Independent Scotland's last gasp forgotten in Panama jungle

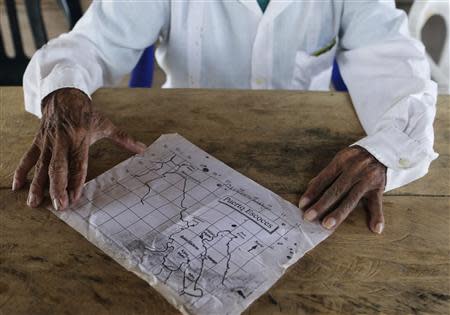

By Dave Graham CALEDONIA, Panama (Reuters) - A few years before giving up its independence, Scotland took a bold gamble to secure a brighter future, founding a colony on the isthmus of Panama to corner trade between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. The 1698 venture ended in tragedy, helping to push Scotland into political union with England and form the United Kingdom. But had it succeeded, Scots might have no need to vote in the referendum on independence this coming September. Named after the gulf where modern Panama and Colombia meet, the Darien scheme was hamstrung from the start by poor planning and English opposition. In less than two years, disease and attacks from the Spanish Empire had wiped out more than half the 2,800 Scottish settlers, and the colony was abandoned. Barely a shadow of it lingers in the bay known locally as Puerto Escoces (Scottish Harbour), where the Scots founded the colony of New Caledonia with an initial contingent of 1,200. "There's nothing there now. Nothing," said Amalio Hackin, 47, a former resident of Puerto Escoces and ethnic Kuna, an indigenous people that in 1700 fought with the Scots against the Spanish, then the dominant colonial power in Central America. Instead of the chatter of Scottish voices, only the shrill drone of cicadas can be heard in the mosquito-ridden jungle where the Scots once dreamed of building a town, New Edinburgh. Mangroves and mud flats have devoured the site. Among the spider webs, giant palms and tangle of creepers that fill the jungle, mere hints of forgotten dwellings appear in clearings. After the colony failed, Scotland in 1707 signed the Act of Union with England, swapping independence for shared trading rights, representation in Westminster and money - much of it to compensate the stricken shareholders of the Darien scheme. Few seriously argue the September 18 vote on independence called by the separatist Scottish National Party (SNP), which runs Scotland's devolved regional government, implies the same risk. But that has not stopped some SNP critics from raising the spectre of Darien to flag the perils of independence, which all the main parties in the British parliament oppose. Time, and Scotland, have moved on, the SNP says. "Scotland has a long history as an outward-looking, adventurous, enterprising nation, and the Darien episode is part of that story. But we have come a long way since the days of late 17th century colonialism," said a spokesperson for Humza Yousaf, external affairs minister of the SNP government. 'KEY OF THE UNIVERSE' In 1979, archaeologists uncovered relics of the colony, including tools, musket balls and a well during an excavation of its old fort. But the jungle soon reclaimed the site. Today, even in Caledonia, an island village of bamboo huts a few miles offshore that is also known as Coedub, local Kuna know nothing of how their forebears fared with the Scots. Seated on hammocks in their congress hall, hat-wearing Caledonia elders mixed up Edinburgh with Hamburg, were unsure where Scotland is and chuckled at a description of kilts. But Caledonia's chief, Aristoteles Cabu, and the elders listened closely to the tale of why the Scots came. "Thank God for sending them home again," the 71-year-old Cabu said finally. "Things would have been different here." Darien's mastermind was William Paterson, a Scot who played a pivotal role in the foundation of the Bank of England in 1694. A year later, Paterson helped create the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies to run the colony he hoped would be a "door of the seas and key of the universe" for a nation hit by economic crisis, famine and English trade curbs. English investors were initially due to take part in the company. But, worried it would hurt England's trading interests and upset Spain, King William III pressured them to withdraw. His opposition angered the Scots, whose crown - but not parliament - was united with England in 1603 when William's great-grandfather, James VI of Scotland, became king of England. Still, Paterson was an astute salesman and the Company of Scotland raised 153,448 pounds from a broad sweep of investors ranging from landowners to merchants, said Douglas Watt, author of "The Price of Scotland", a 2007 book about the Darien scheme. Though the sum fell short of the amount initially pledged, it was probably equivalent to about 20 percent of the liquid wealth in Scotland at the time, Watt added. Wealth is conspicuously absent in Caledonia, part of a semi-autonomous Kuna homeland. Running water is limited, electricity arrived a year ago and toilets are holes giving into the sea. DEATH AND DISEASE Problems began before the Scots had even left for Darien, with the Company of Scotland overpaying for ships and losing a large sum to fraud. By the time the first five vessels arrived, disease had claimed dozens of lives and the toll soon mounted. The directors reported that "in fruitfulness this country seems not to give place to any in the commercial world", but food was scarce and trading the cloth, linen and other goods the Scots brought proved hard. Spanish attacks added to their woes. King William dealt the final blow, ordering nearby English colonies to deny any assistance to the Scots. In June 1699, the exhausted survivors left New Caledonia for New England. Very few of them ever saw Scotland again. To some modern scholars like Watt, the Darien scheme was "vastly optimistic" and was never going to succeed. "It was the wrong location. Scotland was a minor power, it didn't have the naval back-up to control areas in Central America. And all the capital was put into this one venture," he said. "It's a very early example of a huge corporate cock-up." Other experts are less sure. Helen Paul, an economic historian at Southampton University, said many colonial ventures faced similar hardships but some replaced their dead in time to survive. Darien might have done the same if William III had not "stuck in the knife", she said. News of the disaster was slow to reach Scotland and more settlers set sail for Darien in summer 1699. There they met stiffer resistance from Spain and were forced out by April 1700. Now, their last traces are vanishing. In 2011, Panama's Congress changed the name of Puerto Escoces to Puerto Inabaginya in honour of a Kuna hero from a village nearer to Panama City. But it did not get Caledonia's vote. "It's dirty politics," said Apolonio Arosemena, Caledonia's village clerk. "The correct name is Puerto Escoces." (Additional reporting by Belinda Goldsmith in Aberdeen; Editing by Kieran Murray)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News