Inquiries should rebuild faith in our institutions, not conveniently kick problems into the long grass

How far back does accountability stretch? The Bible tells us the sins of the fathers can be visited upon the children even to the third and fourth generation. What if the father isn’t a man, though, but an institution? What if the institutional staff involved in a crime are now dead? The biblical answer being rather frowned upon nowadays, we have developed a new catch-all answer: set up an inquiry.

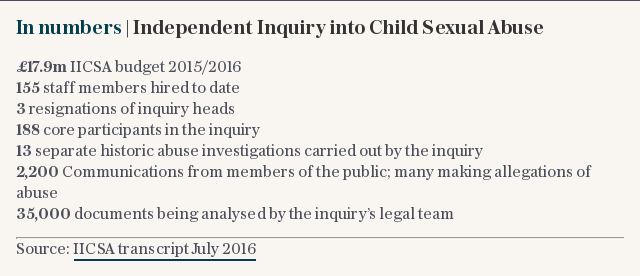

In the last two weeks, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) has been holding the first of many hearings to demand answers from institutions suspected of facilitating abuse. Victims involved in the current investigation gave their testimony in February and now, it is the institutions’ turn.

The current investigation – the only one to hold any hearings so far – looks at the child migration programme, a government-sponsored, charitably-run scheme that sent 130,000 British children to far-off Commonwealth countries to live at boarding schools or with adoptive families. In its day, it was supported by royalty and feted for spreading British influence and helping wayward or orphaned youth.

Over time, however, disturbing reports began to surface: some of the children were being deported without parental consent and subjected to unbearable conditions or abuse when they arrived. The migrations were stopped in the early Seventies. Today, about 2,000 victims are still alive. Those who sponsored and ran the schemes are not.

The victims at first struggled to be heard, but eventually, the enormity of the wrongdoing and negligence started to be recognised. A parliamentary committee took up their case in the late Nineties. In 2010, then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown apologised on behalf of the government for its role in the deportations and funded family reunifications.

While the full list of crimes will never be known, the poor record of the migration programme is now well-established. This gives rise to an obvious question. If we know all of this, why are we holding an inquiry to find it out?

The more you consider the question, the more remarkable it appears. The inquiry is not there to interrogate claims of abuse. It is not there to hold to account the abusers, negligent charities or officials who have, appallingly, escaped justice. There are no useful lessons for the design of some theoretical, future child migration scheme.

Indeed, none of the institutional witnesses were directly involved. Take the example of Nigel Haynes, the former head of a charity called Fairbridge UK. Mr Haynes has been compelled to testify at IICSA to discuss the Fairbridge Society, a predecessor charity that, many decades ago, was Britain’s biggest sender of child migrants.

Mr Haynes had never heard of the charity’s child migration programme when he took over at Fairbridge in 1993. After all, Fairbridge had been merged into the Princes’ Trust portfolio, changed its charitable remit from migration to mentoring deprived youth, rewritten its constitution and changed all its staff. Mr Haynes’ testimony was nonetheless deemed crucial.

Perhaps, you might say, his appearance helped IICSA serve another purpose: to deliver cathartic, public recognition for victims. Yet it even fails in this task. Its terms of reference limit the investigation only to sexual abuse and do not include other kinds, like beatings, malnourishment or forced labour. What the Government is effectively funding is an academic study, based, in large part, on close reading of archival material. This is the stuff of historians, not live legal inquiries, as shown by fact that the inquiry’s key expert witness is, in fact, a historian.

The child migration investigation is, unfortunately, not unique. Just think of John Chilcot’s Iraq Inquiry. It took seven years, cost millions and concluded, in a mere 2.6 million words, that the war was a bad idea, badly executed.

Contrast both of these exercises with the recent Hillsborough inquests, which, for the first time, overturned years of denial and smears to put the fact of 96 unlawful deaths on official record.

They delivered not just new information, leading to six prosecutions, but formal recognition that the 27-year battle by victims’ families was justified. The inquiry did what an inquiry ought to do: it set out to reveal new facts or learn new lessons and it raised the chances of being able to deliver compensation and hold people or organisations accountable.

All societies suffer crises of confidence in their institutions. They reckon with organisational crimes and cover-ups, corruption, denial, malice and negligence. Sometimes, as with the Grenfell Tower fire, the right approach is to set up a comprehensive government inquiry, and damn the cost. But inquiries are also too often used as a way to kick controversies into the next electoral cycle or soak up the heat from persistent conspiracy theories.

The child sexual abuse inquiry is the archetypal political ragbag. It was convened in direct response to a conspiracy theory, after Labour MP Tom Watson disgracefully used unsubstantiated evidence to perpetuate the idea of a Westminster paedophile ring. Its “investigations” include two ludicrously vague lines of inquiry, one entitled “Westminster” and the other, “the Internet”.

It is important to note that it isn’t a total write-off. Its other investigations, targeted more narrowly at recent events, might well shine new light onto unexamined institutional failings in churches, schools, local councils and prisons.

The migration hearings, however, show exactly what a government inquiry should not do, which is to put known historical events on trial and then compel testimony from witnesses who know nothing about them. The child migration programme is a shameful episode from a harsher, crueller past. It should be taught in schools or universities. Its victims should be recognised and, even though it will be inadequate, compensated.

But reliving our history in order to serve a political agenda does not help the country learn nor restore trust in its institutions. Instead, it achieves the exact opposite. Politicians should take heed. Inquiries are powerful tools. They should be handled with care.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News