How the Iraq war unfolded – as reported by The Independent

Twenty years ago, in the early hours, the first bombs fell on Baghdad – the start of an invasion that would lead to years of war for British and American troops, countless civilian and military losses, and a political vacuum into which terrorists took hold and inflicted further unspeakable cruelties on the people of Iraq.

With two decades’ hindsight, the wrongs of this catastrophic strategic blunder are clear to all but a few. After all, there were no weapons of mass destruction. But it is easy to forget that, in the heat of the debate in 2002 and 2003, the majority of the press and politicians were swayed by the Bush administration and, in Britain, the Blair government’s torrent of propaganda, most notoriously the “sexed-up” dossier claiming Saddam Hussein could launch WMDs within 45 minutes.

Not so The Independent; we, as ever, looked critically at the claims made and formed our own conclusions. We decided these claims did not add up. As almost a lone voice, we questioned the official line all the way through the arguments for war to the tragedy of Dr David Kelly’s death, the whitewash of the Hutton report and the other inquiries that followed. All the while, our reporters on the ground gave a voice to the voiceless across a nation torn apart by conflict. Here, then, is how the road to the Iraq war and the pitiless conflict that ensued unfolded on the pages of The Independent.

Genesis: Axis of evil

29 January 2002: Giving his first State of the Union speech, George W Bush told America that his war on terror was just beginning.

The president, enjoying a record wave of popularity, pledged to bring tens of thousands of terrorists to justice in the wake of 9/11, reported Rupert Cornwell from Washington. He wrote: “Nor would America permit rogue regimes to wield weapons of mass destruction, said the president, singling out Iraq and North Korea by name.” The speech was the first time Bush referred to Iraq and the now-infamous “axis of evil”, a phrase that rang around the world and reverberates to this day. What Bush did not say was that what became a demand for “regime change” and removing Saddam was unfinished business from the first Gulf War in 1991. The Western coalition, led by Bush’s father Geoge HW Bush, drove Saddam out of Kuwait – but stopped at the border and left the dictator in place.

The road to war

February to April: From Bush’s comments in January, Britain’s move towards war began. At the end of February, Tony Blair backed America on Iraq after holding a phone call with Bush. Political editor Andrew Grice wrote that the PM told his cabinet “he supported American determination to act over Iraq but insisted no decisions had been reached yet”. It became clear later that there was no doubt Blair would support Bush, even as he urged the Americans to secure UN approval for armed intervention. At home, the rifts were quick to appear – the next day, we reported a warning to Blair that he would face a ministerial rebellion if he joined US military action.

There was, too, a taste of the controversies to come; on 13 March, we reported on Jack Straw, the foreign secretary, claiming Saddam Hussein’s regime could have a nuclear bomb within five years. He told backbench Labour MPs: “There is huge published, compelling evidence about Saddam Hussein and the Iraqi regime’s complicity in the production of weapons of mass destruction.”

Less than two weeks later, defence secretary Geoff Hoon insisted Britain could join a military strike without gaining approval from the United Nations.

At the ranch

5 April: Blair travelled to the president’s ranch in Crawford, Texas, spending hours talking about Iraq with Bush. The result was the PM’s most explicit threat yet, echoing Bush’s language that Iraq would face “regime change” if UN weapons inspectors were not allowed into the country.

Reporting from Texas, Paul Waugh and Colin Brown wrote: “Use of the phrase ‘regime change’ marks an important strengthening of Mr Blair’s rhetoric, clearly echoing the White House’s increasingly bellicose language since 11 September. It signals a break by the prime minister from traditional Foreign Office caution on the issue.”

Crossing the Rubicon

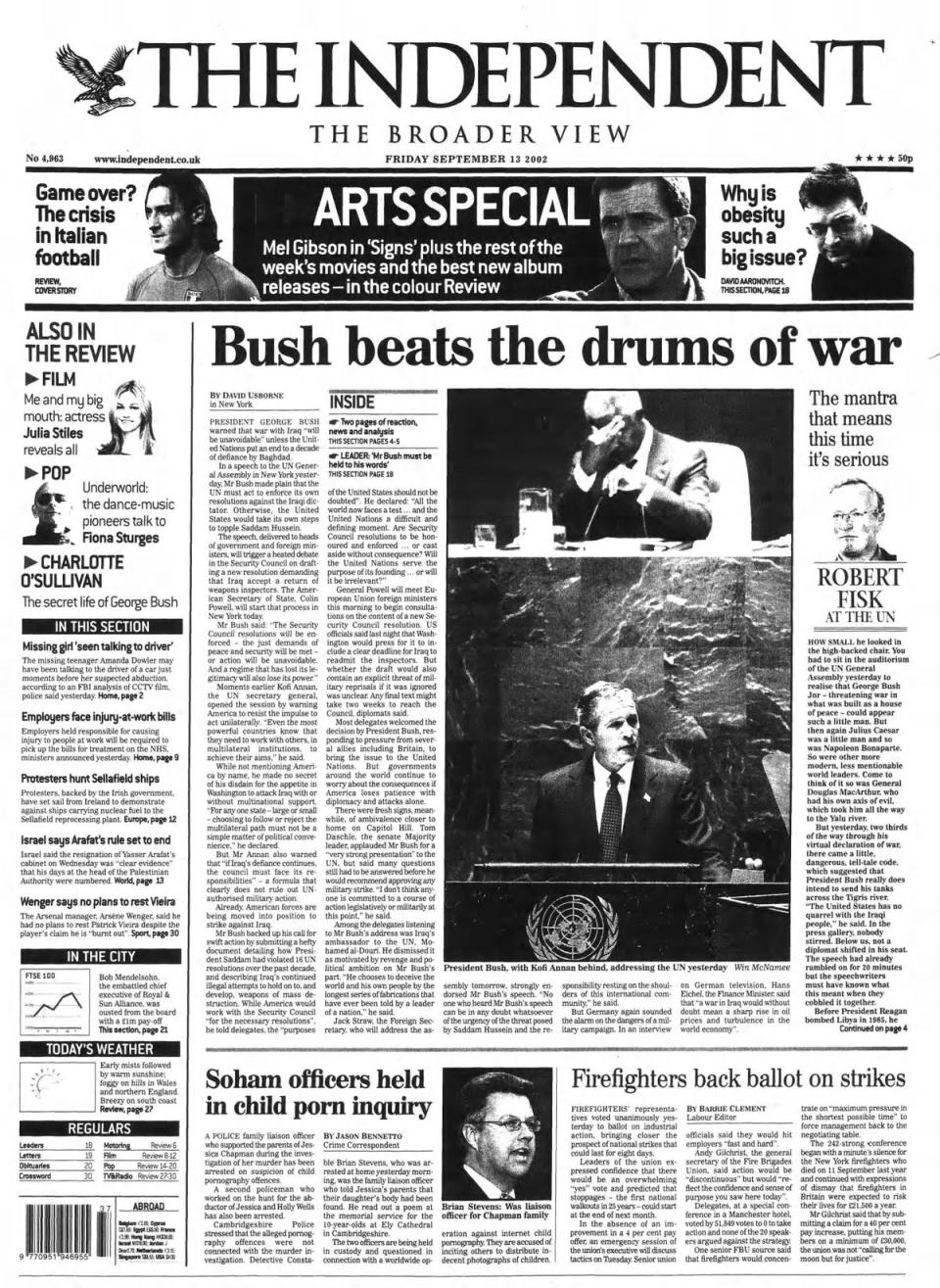

10 September: At the United Nations General Assembly, almost exactly a year after 9/11, Bush told world leaders the US would take steps of its own if the UN did not enforce its resolutions against Saddam. “Bush beats the drums of war”, read our front page the next day.

Robert Fisk wrote: “Two-thirds of the way through his virtual declaration of war, there came a little, dangerous, tell-tale code, which suggested that President Bush really does intend to send his tanks across the Tigris river.” He was referring to Bush’s assertion that “the United States has no quarrel with the Iraqi people”, echoing the words of his father before the first Gulf War, and Ronald Reagan in 1985, about Libya. This was the moment, wrote Fisk, that Bush Jr crossed his own Rubicon.

The dossier

24 September: Blair set out the case for war in the government’s long-awaited dossier. Over 50 pages, its claims included that Saddam had chemical and biological weapons that were deployable within 45 minutes. The document could not convince 53 of his own backbenchers, who voted against the government despite the PM telling the Commons: “Our purpose is disarmament. No one wants military conflict.”

Over eight pages of news and analysis, the next day’s Independent laid out the dossier in full. And in the editorial, our view: “Saddam may be a risk to peace, but Mr Blair has failed to make the case for war against Iraq.”

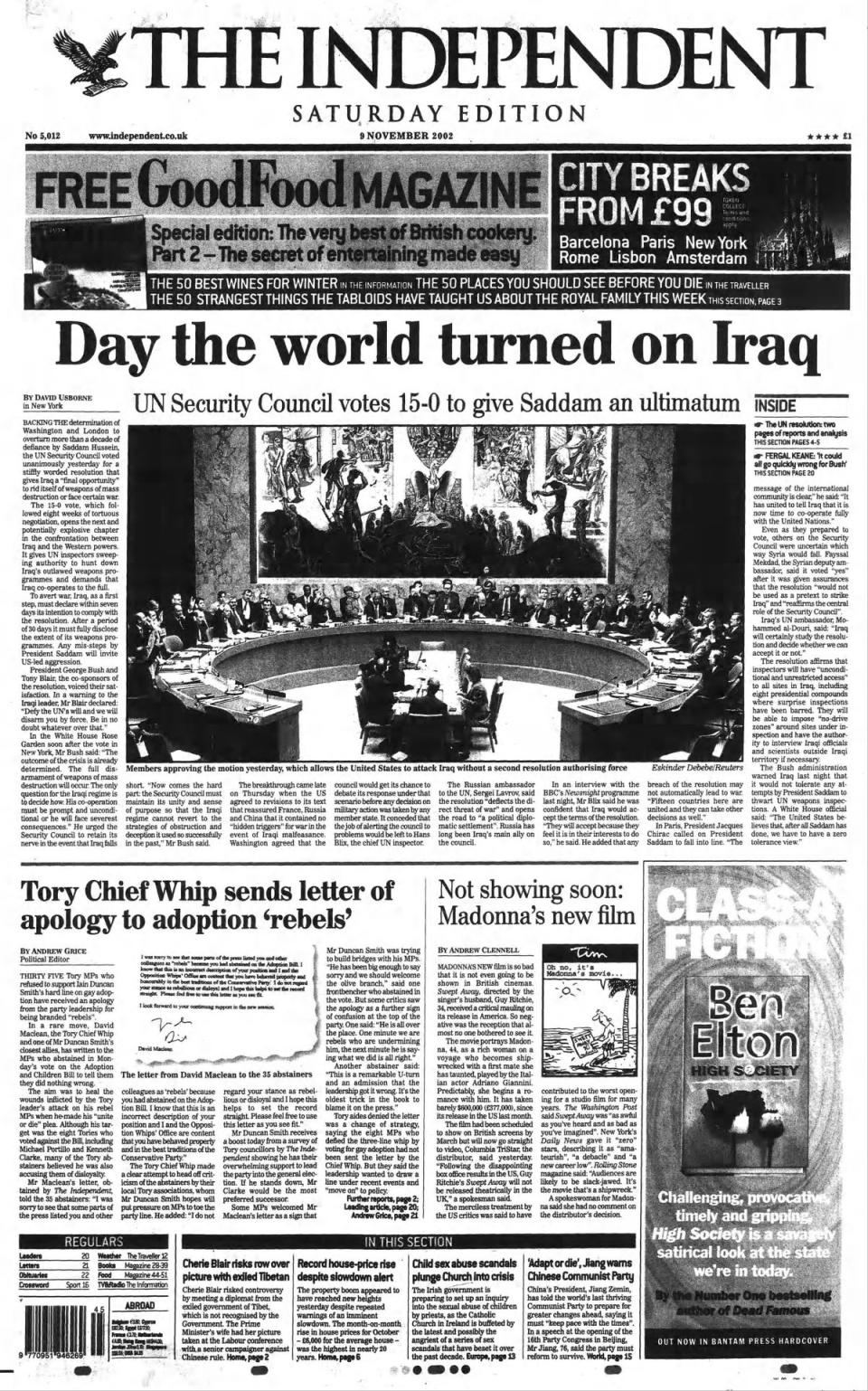

Day the world turned on Iraq

9 November: “Backing the determination of Washington and London to overturn more than a decade of defiance by Saddam Hussein, the UN Security Council voted unanimously yesterday for a stiffly worded resolution that gives Iraq a ‘final opportunity’ to rid itself of weapons of mass destruction or face certain war,” wrote David Usborne from New York on 9 November 2002’s front page.

After eight weeks of negotiation, the security council voted 15-0 for resolution 1441, instructing Iraq to comply with UN weapons inspectors. In a warning to the Iraqi leader, Blair declared: “Defy the UN’s will and we will disarm you by force. Be in no doubt whatever over that.”

Hunt for weapons

November 2002 to February 2003: Over the next few months, weapons inspectors encountered reluctance from Iraq – but failed to find a smoking gun. On 28 January 2003, our report from New York read: “Hans Blix, the chief weapons inspector, delivered a harsh but inconclusive report on the disarmament of Iraq before the UN Security Council yesterday. Filled with red flags suggesting grave violations but devoid of concrete evidence to prove guilt, it left a worried world unsure which way it should fall – towards war or peace.

“The report did nothing to lower the stakes for George Bush and Tony Blair as the two ponder their options: allowing the inconclusive inspections process to continue for weeks, and maybe even months, or to move towards a military onslaught in the gulf.”

The issue divided Europe, and by the end of January eight countries including the UK were pro-war, while eight more including France and Germany were against. Blair travelled to Washington to urge Bush to seek a further mandate from the UN, but the president resisted. Andy McSmith and Rupert Cornwell in Washington wrote on 1 February: “President Bush made clear last night he would not allow any second UN resolution to delay a decision on war with Iraq. A new resolution would be welcome, he said, but only, ‘if it is yet another signal we are intent on disarming Saddam Hussein’.” The offensive, officials suggested, could begin within just six weeks.

Millions march for peace

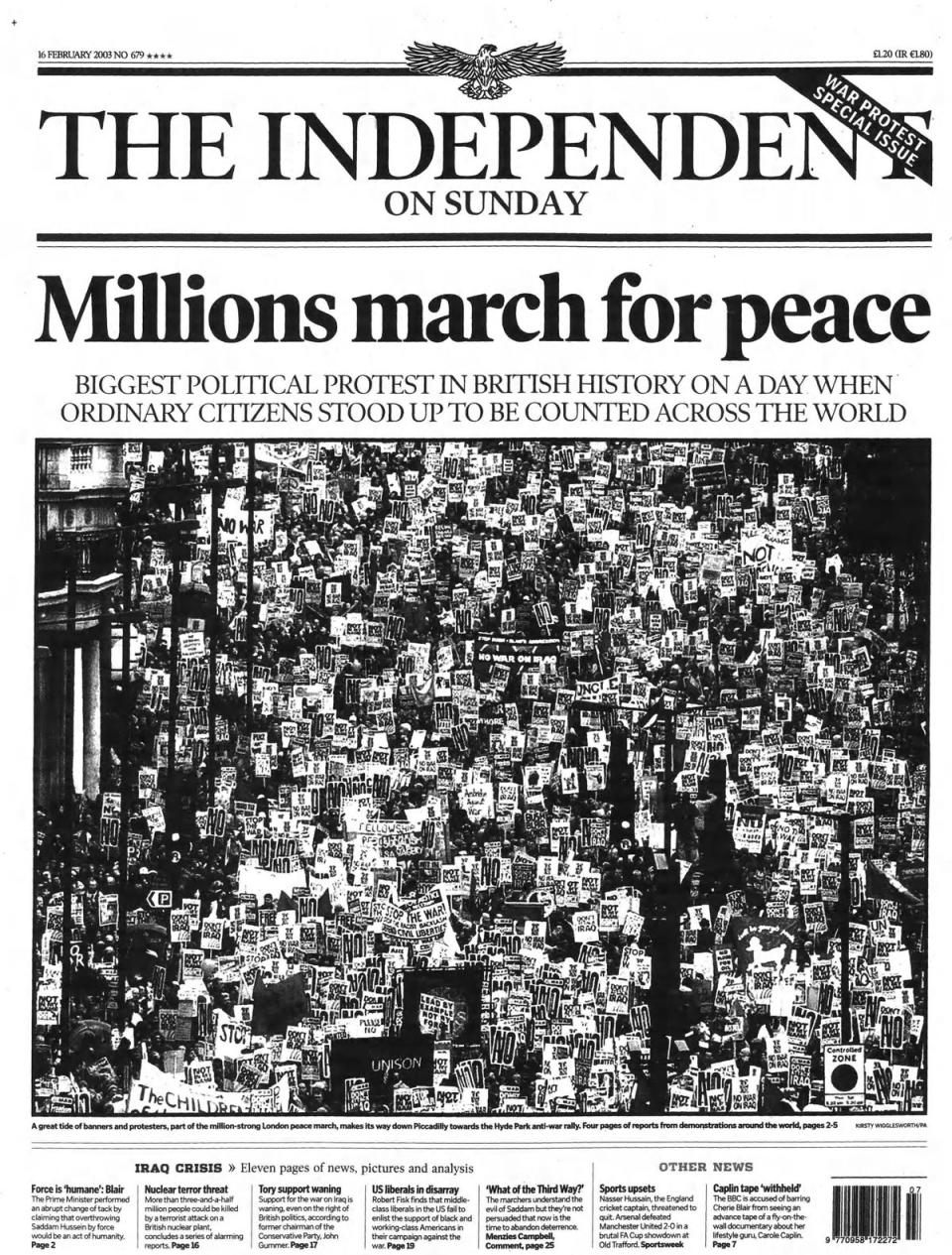

15 February: It was the people’s protest – with war now looming, huge crowds of ordinary citizens took to the streets of London, as well as other cities around the world.

The Independent on Sunday showed a sea of protesters and placards making their way down Piccadilly, beneath the headline: “Millions march for peace”. Inside, the story read: “It was the largest political gathering of any kind in British history and an emphatic popular retort to the prime minister, Tony Blair. This was a million people voting against him with their feet.”

Escalating tensions

February and March: While Blair and Bush faced opposition in the United Nations, the prime minister was also challenged by a Labour revolt – most prominently from international development secretary Clare Short, whom Blair’s allies accused of an “act of treachery” after she threatened to resign unless a move to war was backed by a fresh UN resolution.

By 17 March, hopes of an agreement at the UN had collapsed, and hours later the US announced its intention to push ahead regardless. From Washington, our correspondent Rupert Cornwell wrote: “Exile or war. George Bush handed Saddam Hussein that final stark choice last night as he delivered a 48-hour deadline for the Iraqi dictator to leave the country or face military conflict.”

The darkness is beginning to descend

In Britain, Robin Cook – former foreign secretary and now leader of the Commons – became the first cabinet minister to quit, accusing the government of “diplomatic miscalculations” and telling the Commons he could not “defend a war with neither international agreement nor domestic support”. The Independent’s leading article was unequivocal: “The war that now seems inevitable constitutes a failure of potentially catastrophic proportions, whose consequences will fall first on the long-suffering people of Iraq.” The next day, the Commons gave its approval – but 139 Labour MPs backed a rebel amendment, at that stage the biggest rebellion suffered by a governing party.

From Iraq, Robert Fisk captured the mood of a Baghdad braced for bombardment: “The darkness is beginning to descend, the fog of anxiety that falls upon all people when they realise that they face unimaginable danger.”

Shock and awe

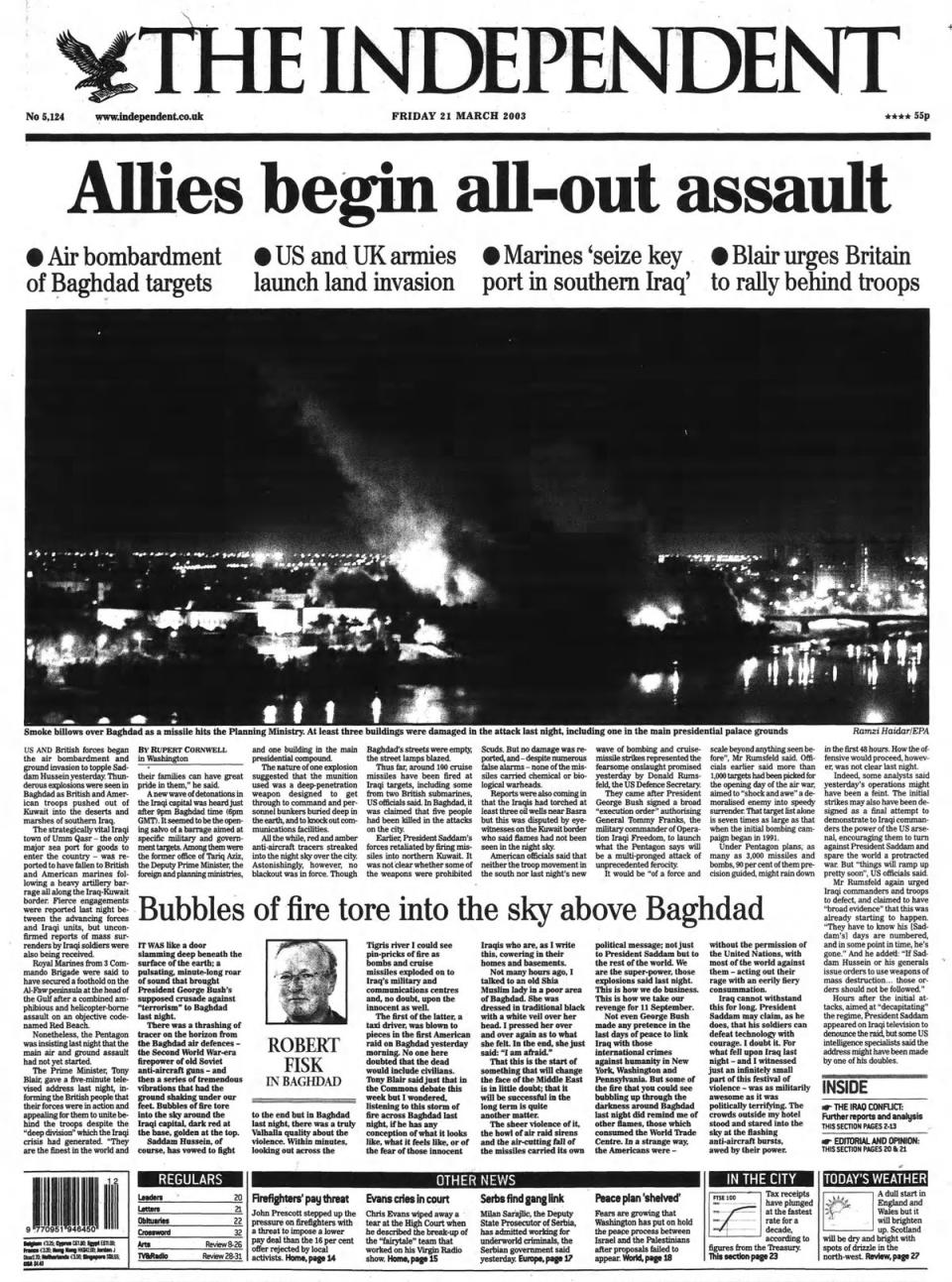

20 March: At 2.20am GMT, the first Tomahawk missile was unleashed from the USS Bunker Hill. After months of escalation, the “shock and awe” campaign that spearheaded Operation Iraqi Freedom had begun. Ten minutes later, air raid sirens wailed across Baghdad as F-117 Nighthawks dropped 2,000lb bombs, explosions shattering the quiet of the pre-dawn city. Iraqi state radio’s normal programming was taken off air, replaced by a new announcer who began, in Arabic: “This is the day we have been waiting for”; the frequency had been taken over by the US military. By 6.45pm GMT, the first troops had entered Iraq over the Kuwaiti border, seizing control of the commercial port town of Umm Qasr.

On The Independent’s front page, which led with the headline “Allies begin all-out assault”, Robert Fisk wrote from the Iraqi capital: “It was like a door slamming deep beneath the surface of the earth; a pulsating, minute-long roar of sound that brought President George Bush’s supposed crusade against “terrorism” to Baghdad last night.

“There was a thrashing of tracer on the horizon from the Baghdad air defences – the Second World War-era firepower of old Soviet anti-aircraft guns – and then a series of tremendous vibrations that had the ground shaking under our feet. Bubbles of fire tore into the sky around the Iraqi capital, dark red at the base, golden at the top.”

We bomb. They suffer

23 April: Over the course of the war, the Iraqi civilian death toll would reach 150,000 according to the Chilcot report – although estimates vary and some put the total significantly higher – with many more wounded. Two days after the initial assault began, The Independent on Sunday devoted its front page to the stories of the first of them, under the headline: “The reality of war. We bomb. They suffer”.

After touring a Baghdad hospital, Robert Fisk wrote: “Donald Rumsfeld says the American attack on Baghdad is ‘as targeted an air campaign as has ever existed’ but he should not try telling that to Doha Suheil. She looked at me yesterday morning, drip feed attached to her nose, a deep frown over her small face as she tried vainly to move the left side of her body. The cruise missile that exploded close to her home in the Radwaniyeh suburb of Baghdad blasted shrapnel into her tiny legs – they were bound up with gauze – and, far more seriously, into her spine. Now she has lost all movement in her left leg.

“Her mother bends over the bed and straightens her right leg which the little girl thrashes around outside the blanket. Somehow, Doha’s mother thinks that if her child’s two legs lie straight beside each other, her daughter will recover from paralysis. She was the first of 101 patients brought to the Al-Mustansiriyah College Hospital after America’s blitz on the city began on Friday night. Seven other members of her family were wounded in the same cruise missile bombardment; the youngest, a one-year-old baby, was being breastfed by her mother at the same time.

War, even when it has international legitimacy – which this war does not – is primarily about suffering

“There is something sick, obscene about these hospital visits. We bomb. They suffer. Then we turn up and take pictures of their wounded children. The Iraqi minister of health decides to hold an insufferable press conference outside the wards to emphasise the ‘bestial’ nature of the American attack. The Americans say that they don’t intend to hurt children. And Doha Suheil looks at me and the doctors for reassurance, as if she will awake from this nightmare and move her left leg and feel no more pain.

“So let’s forget, for a moment, the cheap propaganda of the regime and the equally cheap college hospital. For the reality of war is ultimately not about military victory and defeat, or the lies about ‘coalition forces’ which our ‘embedded’ journalists are now peddling about an invasion involving only the Americans, the British and a handful of Australians. War, even when it has international legitimacy – which this war does not – is primarily about suffering.”

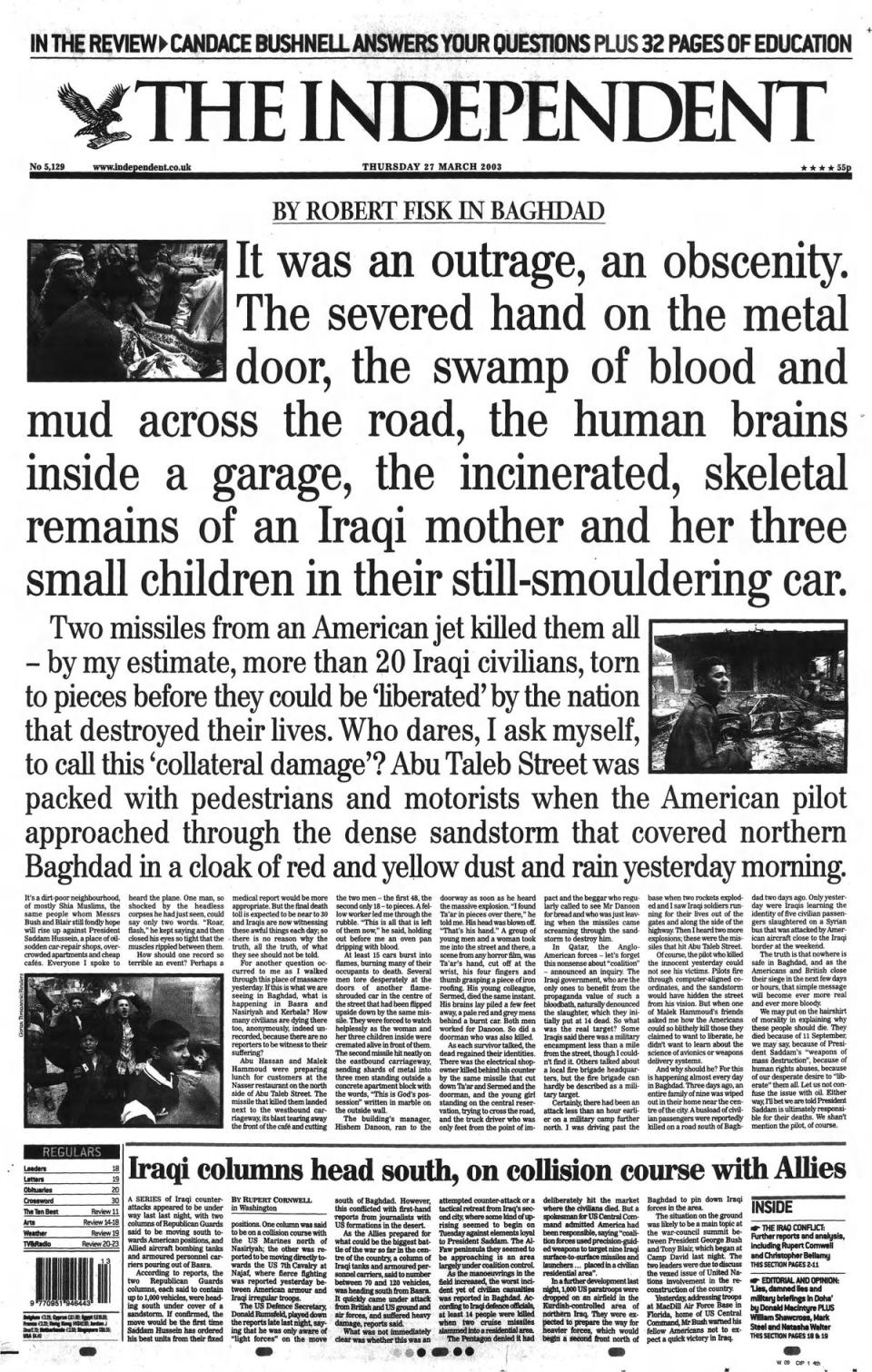

Who dares to call this ‘collateral damage’?

27 March: “It was an outrage, an obscenity,” ran the top line of The Independent’s front page that greeted readers a week after the invasion began. But it was a front page unlike any other – rather than a headline, it displayed Robert Fisk’s startling dispatch in large type across more than half the page.

Amid the euphemisms of “collateral damage”, Fisk’s words brought to life the horror and humanity of Baghdad: “The severed hand on the metal door, the swamp of blood and mud across the road, the human brains inside a garage, the incinerated, skeletal remains of an Iraqi mother and her three small children in their still-smouldering car.

“Two missiles from an American jet killed them all – by my estimate, more than 20 Iraqi civilians, torn to pieces before they could be ‘liberated’ by the nation that destroyed their lives. Who dares, I ask myself, to call this ‘collateral damage’?”

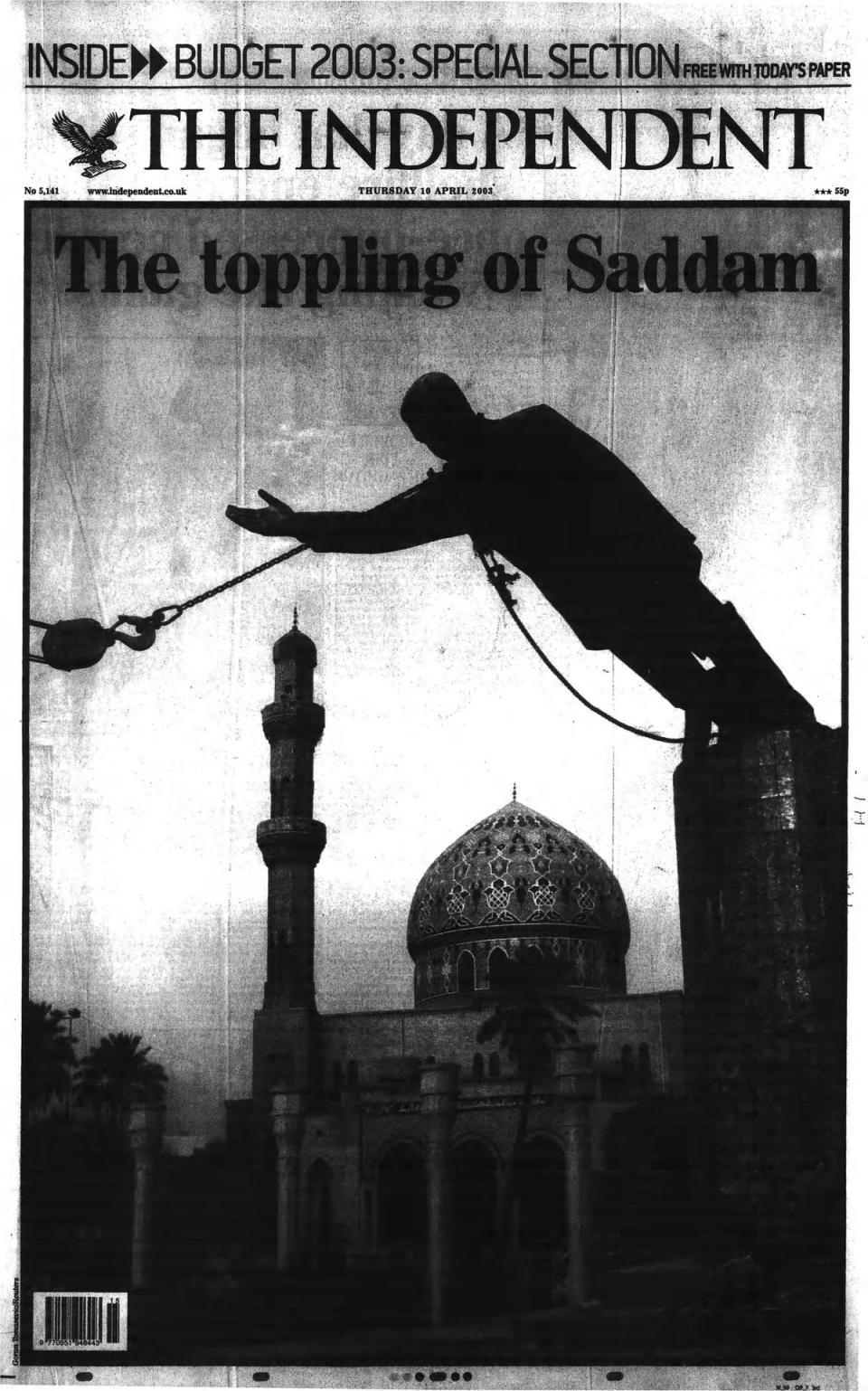

The fall of Saddam

9 April: It is perhaps the iconic image of the Iraq war: the statue of Saddam in Baghdad’s Fardus square toppled, a rope tied around its neck. The symbolic moment took place on the day US forces advanced on the capital after weeks of fighting and swept into the city unhindered.

A witness on the ground that day, Fisk led The Independent’s coverage, writing: “The Americans ‘liberated’ Baghdad yesterday, destroyed the centre of Saddam Hussein’s quarter-century of brutal dictatorial power but brought behind them an army of looters who unleased upon the ancient city a reign of pillage and anarchy. It was a day that began with shellfire and airstrikes and blood-bloated hospitals and ended with the ritual destruction of the dictator’s statues. The mobs shrieked their delight.

“Men who, for 25 years, had grovellingly obeyed President Saddam’s most humble secret policeman turned into giants, bellowing their hatred of the Iraqi leader as his vast and monstrous statues thundered to the ground. ‘It is the beginning of our new freedom,’ an Iraqi shopkeeper shouted at me. Then he paused, and asked: ‘What do the Americans want from us now?’”

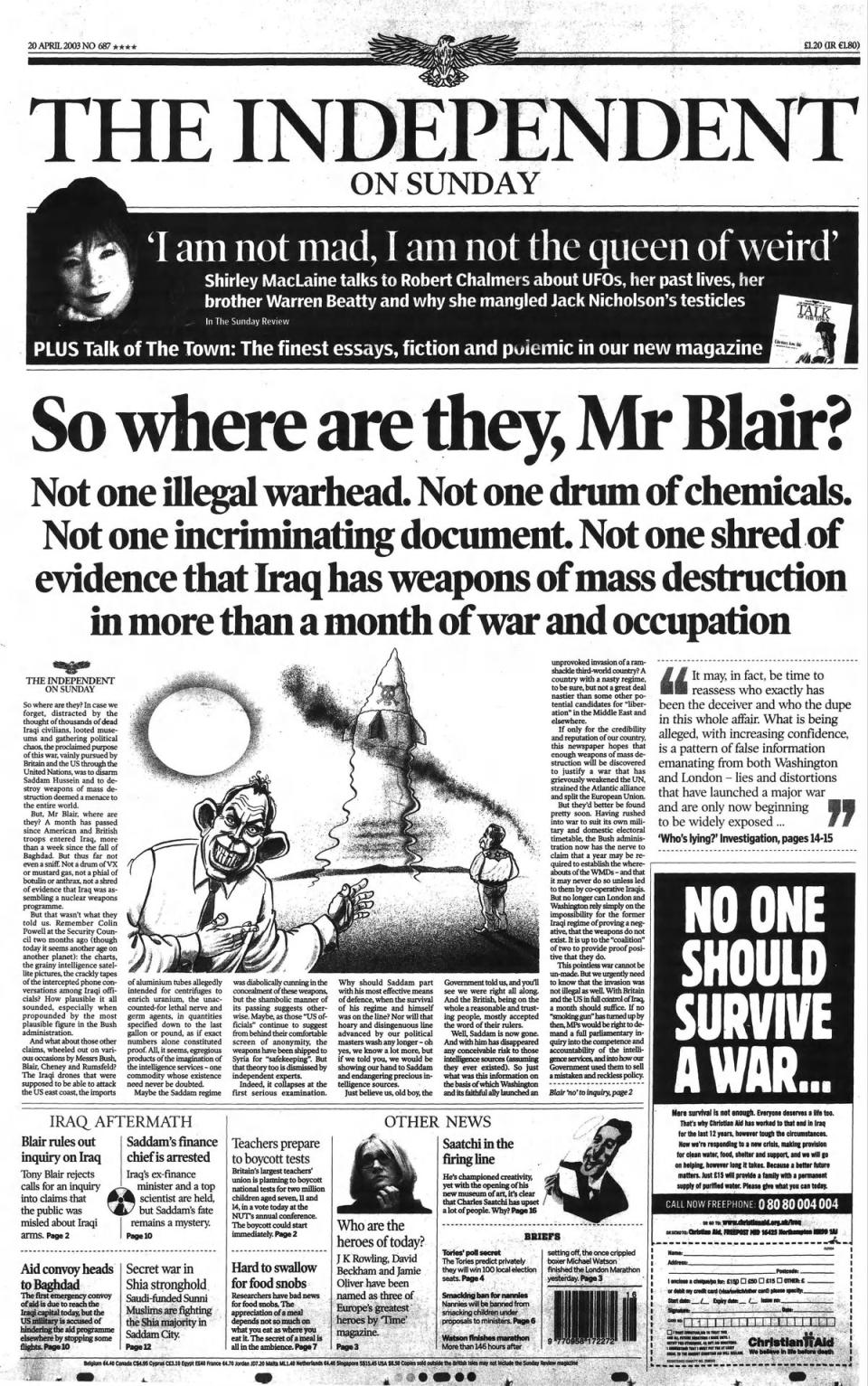

So where are they?

20 April: A month into the war, and not a sign of any WMDs. On 20 April, with a leading article on the front page, The Independent on Sunday asked: “So where are they, Mr Blair? Not one illegal warhead. Not one drum of chemicals. Not one incriminating document. Not one shred of evidence that Iraq has weapons of mass destruction in more than a month of war and occupation.”

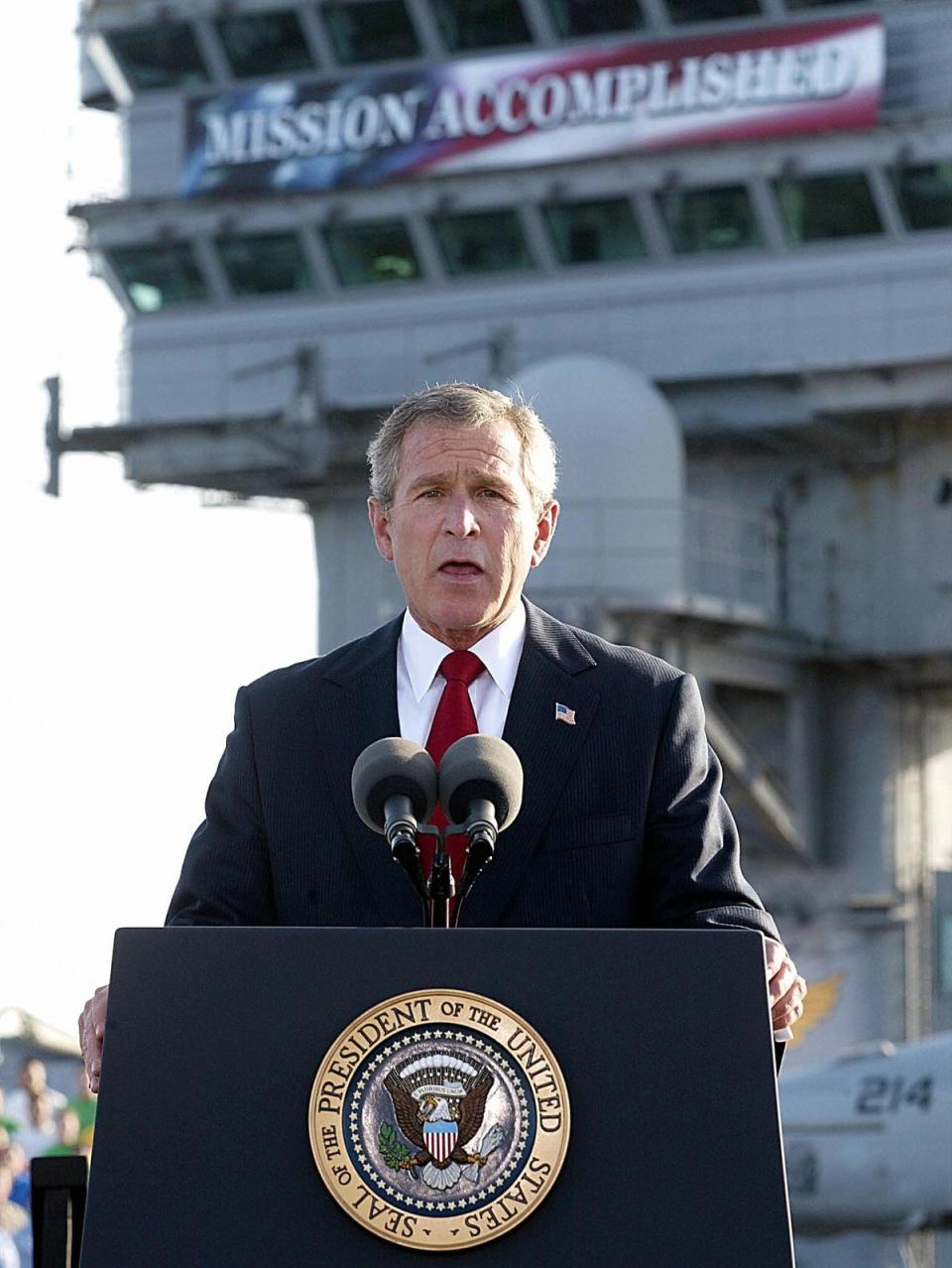

‘Mission accomplished’

1 May: On the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, Bush declared victory in Iraq. Standing beneath a banner reading “Mission Accomplished”, the president told cheering sailors: “We will continue to hunt down the enemy before he can strike.”

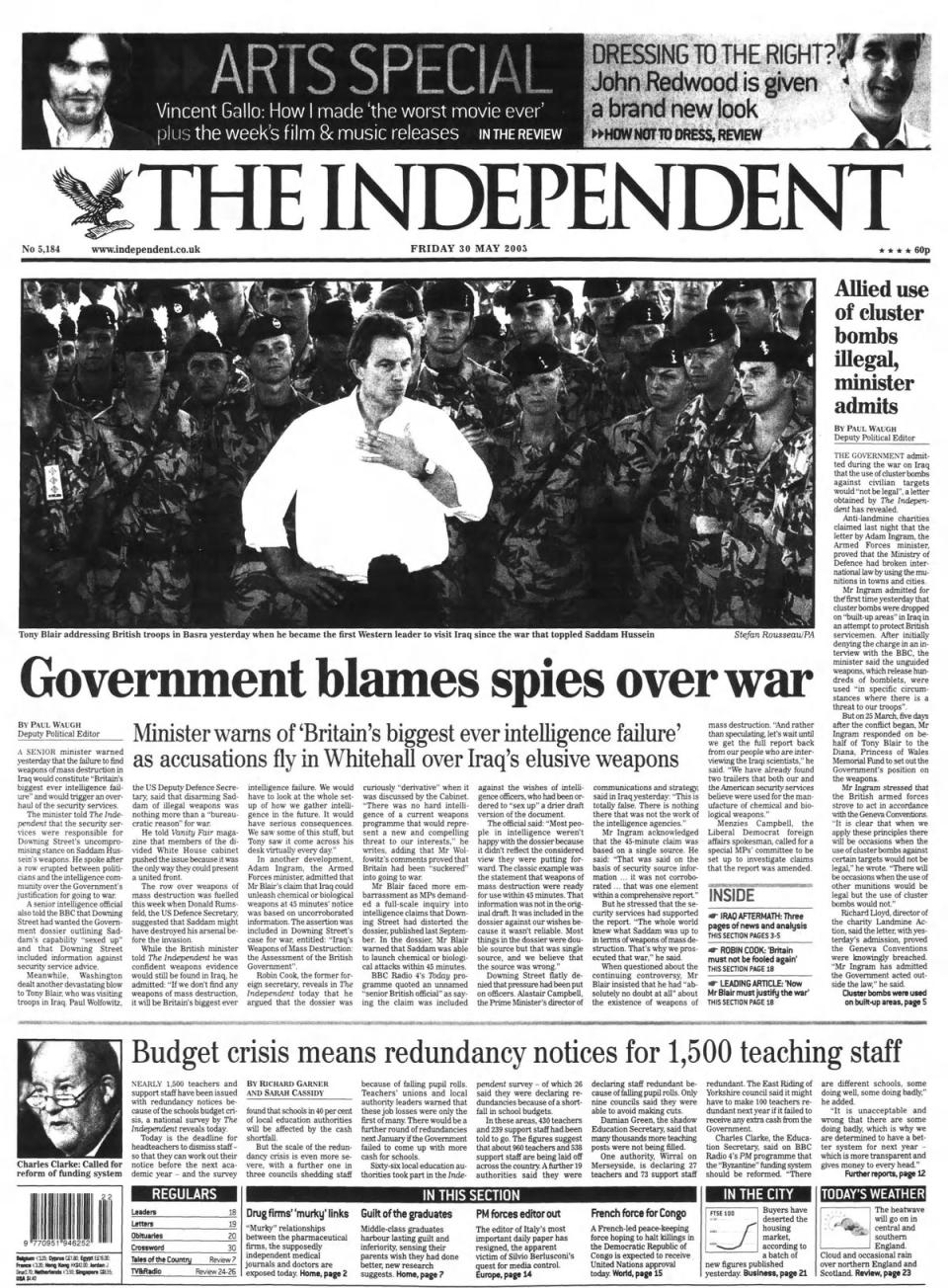

Sexed-up claims

29 May: With still no trace of chemical or biological weapons, British intelligence was once again being called into question. Radio 4’s Today programme quoted a senior official claiming that Downing Street had wanted the government’s Iraq dossier to be “sexed up”, including the 45-minute claim against security service advice. It was a revelation that would lead to the unravelling of Blair’s case for war, as well as having its own tragic consequences. The Independent reported the claims with a senior minister warning that a failure to find WMDs would constitute “Britain’s biggest ever intelligence failure”, while Robin Cook criticised the dossier too, writing on our pages: “There was no hard intelligence of a current weapons programme that would represent a new and compelling threat to our interests.”

From there, questions grew about the reports – now dubbed the “dodgy dossier” – with weeks of claim and counter-claim.

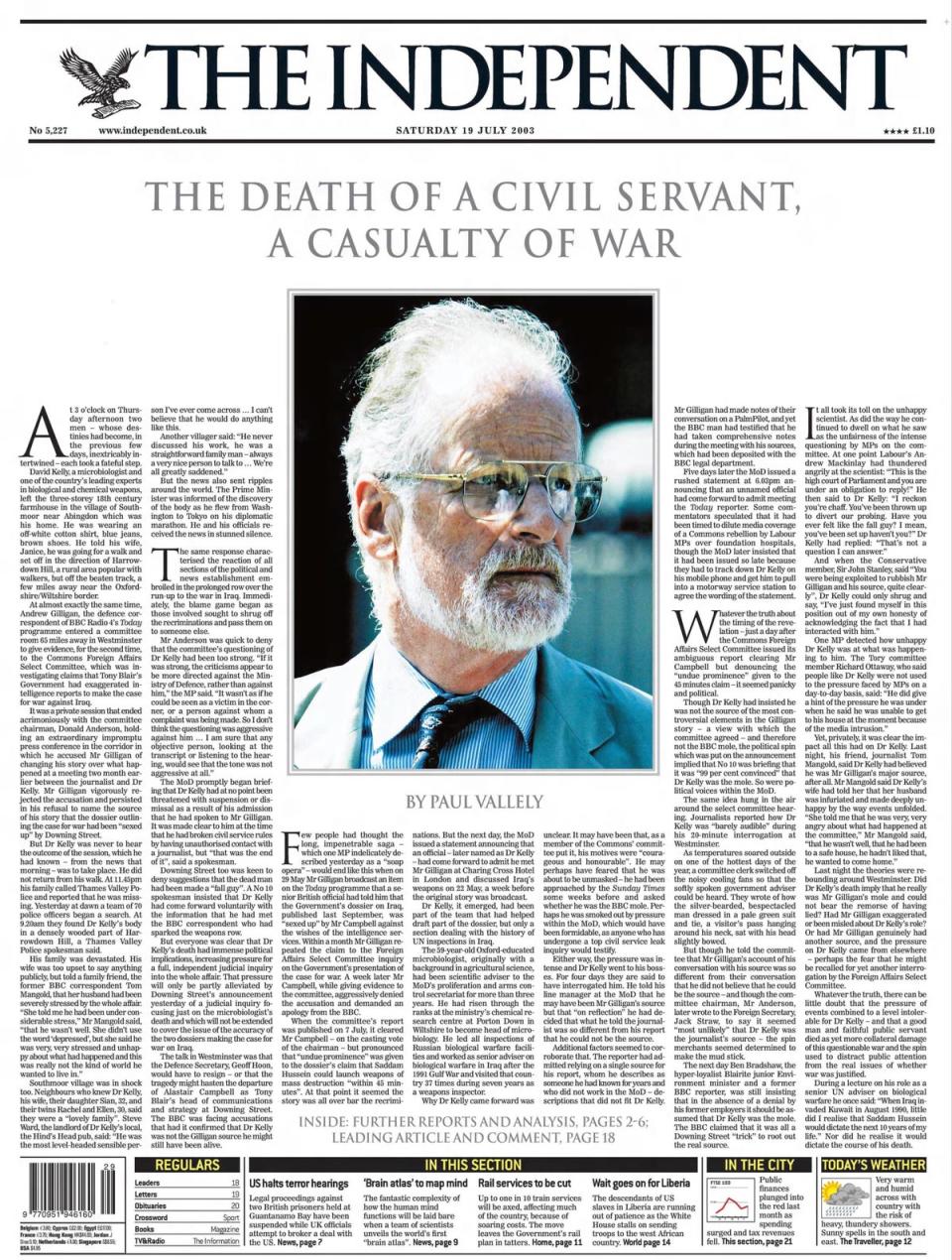

A casualty of war

18 July: With pressure mounting on the government, Dr David Kelly had been identified as the potential source of the leak to Andrew Gilligan, Today’s defence correspondent, putting the media spotlight on the weapons expert. On 18 July, seemingly under intolerable pressure, he took his own life. The next day’s Independent ran a large picture of Dr Kelly with the headline: “The death of a civil servant, a casualty of war”. The article read: “At 3 o’clock on Thursday afternoon two men – whose destinies had become, in the previous few days, inextricably intertwined – each took a fateful step.

“David Kelly, a microbiologist and one of the country’s leading experts in biological and chemical weapons, left the three-storey 18th-century farmhouse in the village of Southmoor near Abingdon which was his home. He was wearing an off-white cotton shirt, blue jeans, brown shoes. He told his wife, Janice, he was going for a walk and set off in the direction of Harrowdown Hill, a rural area popular with walkers, but off the beaten track, a few miles away near the Oxfordshire/Wiltshire border.

“At almost exactly the same time, Andrew Gilligan, the defence correspondent of BBC Radio 4’s Today programme entered a committee room 65 miles away in Westminster to give evidence, for the second time, to the Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee, which was investigating claims that Tony Blair’s government had exaggerated intelligence reports to make the case for Iraq.

“It was a private session that ended acrimoniously with the committee chair, Donald Anderson, holding an extraordinary impromptu press conference in the corridor in which he accused Mr Gilligan of changing his story over what happened at a meeting two months earlier between the journalist and Dr Kelly. Mr Gilligan vigorously rejected the accusation and persisted in his refusal to name the source of his story that the dossier outlining the case for war had been “sexed up” by Downing Street.

“But Dr Kelly was never to hear the outcome of the session, which he had known – from the news that morning – was to take place. He did not return from his walk. At 11.45pm his family called Thames Valley Police and reported that he was missing. Yesterday at dawn a team of 70 police officers began a search. At 9.20am they found Dr Kelly’s body in a densely wooded part of Harrowdown Hill, a Thames Valley Police spokesman said.”

‘Ladies and gentlemen – we got him’

13 December: Close to his hometown of Tikrit, Saddam Hussein – armed with a pistol – was found in a cellar by US forces after intensive searches of the surrounding area. A videotape was later released of him undergoing medical tests. In his dispatch from Baghdad for Monday 15 December’s Independent, Fisk wrote: So they got Saddam at last. Unkempt, his tired eyes betraying defeat, even the $750,000 found in his hole in the ground demeaned him.

“Saddam in chains; maybe not literally, but he looked in that extraordinary videotape yesterday like a prisoner of ancient Rome, the barbarian cornered, the hand caressing the scraggy beard. All those ghosts – of gassed Iranians and Kurds, of Shias gunned into the mass graves of Karbala, of the prisoners dying under torture in the villas of Saddam’s secret police – must surely have witnessed something of this.

“‘Ladies and gentlemen – we got him,’ crowed Paul Bremer, the American proconsul in Iraq. ‘This is a great day in Iraq’s history. For decades, hundreds of thousands of you suffered at the hands of this cruel man. For decades, this cruel man divided you against each other. For decades, he threatened to attack your neighbours. These days are gone for ever... the tyrant is a prisoner.’”

Whitewash?

28 January 2004: Lord Hutton, appointed by the government to carry out an inquiry into the circumstances around Dr David Kelly’s death, delivered his findings, and The Independent’s view was clear: “Whitewash?”

The special issue had a stark white front page that became one of The Independent’s most impactful – and most famous. It carried the words: “Eight months ago, BBC reporter Andrew Gilligan broadcast his now infamous report casting doubt on the government’s dossier on Iraq’s weapons capability, a vital plank in its case for war. In the ensuring furore between No 10 and the BBC, government scientist David Kelly, who was revealed to be Gilligan’s source, was found dead in the woods. Tony Blair appointed Lord Hutton, a former Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland, to hold an inquiry into the circumstances surrounding Dr Kelly’s death. He listened to 74 witnesses over 25 days, and yesterday published his 740-page report. In it, he said Gilligan’s assertions were unfounded and criticised the BBC, whose chair has now resigned. He said that Dr Kelly had broken the rules governing civil servants in talking to journalists. He exonerated Tony Blair, cleared Alastair Campbell and attached no blame to the government for the naming of Dr Kelly. So was this all an establishment whitewash? And what of the central issue which Lord Hutton felt he could not address? If the September 2002 dossier which helped persuade the nation of the urgent need for war (and triggered this tragic chain of events) was indeed reliable, where, exactly, are Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction?”

Death of a tyrant

30 December 2006: At 6.10am, just before dawn, Saddam Hussein was hanged in northern Baghdad. At the start of November he had been sentenced to death over the deaths of 148 people in the town of Dujail during the 1980s. The execution was not broadcast, but Iraqi TV showed footage of Hussein walking to the gallows, and later pictures of his body wrapped in a shroud.

The Independent’s front page showed the first picture of the executed Hussein with the headline “The dead dictator”. Our story read: “As they put the rope around his neck, the 69-year-old former dictator muttered to himself, ‘Do not be afraid.’ It was still dark outside. The sun had not yet risen. The call to prayer had not yet sounded in the city that Saddam Hussein al-Majid al-Tikrit once ruled through fear.

“Now he stood shackled in a prison in the northern suburb of Baghdad – the same prison in which his own secret service, al-Mukhabarat, once tortured and killed. The trapdoor at his feet had opened for countless others, on his orders. His own death would be almost as brutal.

“The executioner offered Saddam a hood to cover his face during those final moments, but it was refused. ‘God is great,’ said the condemned man. ‘The nation will be victorious. Palestine belongs to the Arabs.’

“As he recited the ‘Shahada’, a Muslim prayer that says there is no god but God and Muhammad is his messenger, for a second time, he was brought to an abrupt end. As he reached the word Muhammad, a lever was pulled, the trapdoor swung and his body dropped. Half a metre, no more. It was enough. ‘The tyrant has fallen,’ someone in the group of onlookers shouted. An eyewitness said: ‘We heard his neck snap instantly.’

“Saddam Hussein, the Butcher of Baghdad to some but a martyr to his remaining followers, was dead. He had been executed for crimes against humanity. Film of the seconds leading up to his death was broadcast as proof that the once unbelievable was now true. Bombs were set off by Sunni Muslims loyal to him; but Shias, whose sect he had oppressed, danced in the streets and fired into the air.”

Spinning on their graves

6 July 2016: Seven years after it was announced by Gordon Brown, the Chilcot inquiry into the Iraq war published its report, and the verdict was damning. The invasion had been unnecessary; its support achieved through misrepresentation of evidence, while those who opposed military action were sidelined and belittled. Troops were under-equipped for war, while minimal thought was given to the shell of a nation that would be left behind.

Blair, though, saw it differently. The former prime minister declared that his decision to take Britain to war had been made “in good faith” and, with the same information, he would have done so again. With more than 150,000 Iraqi civilians and 179 British servicemen and women dead on the back of that decision, The Independent’s verdict on the former premier was clear: “Spinning on their graves.”

On the 2.6 million words of the Chilcot report, our leading article was succinct: “In short, the slaughter of Iraqi innocents in which Britain colluded was the biggest and most consequential blunder in recent global history, and can never be forgiven.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News