Iraqi militant leader refused to fall into line

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — He has commanded a relentless bombing campaign against Iraqi civilians, orchestrated audacious jailbreaks of fellow militants and expanded his hard-line Islamist organization's reach deep into neighboring Syria.

While his may not be a household name, the shadowy figure known as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has emerged as one of the world's most lethal terrorist leaders. He is a renegade within al-Qaida whose maverick streak eventually led its central command to sever ties, deepening a rivalry between his organization and the global terror network.

Al-Baghdadi's Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant is the main driver of destabilizing violence in Iraq and until recently was the main al-Qaida affiliate there. Al-Qaida's general command formally disavowed the group this week, saying it "is not responsible for its actions."

Al-Baghdadi took over leadership of al-Qaida's main Iraq franchise following a joint U.S.-Iraqi raid in April 2010 that killed the terror group's two top figures inside Iraq at their safe house near Tikrit, once Saddam Hussein's hometown. Vice President Joe Biden at the time called the killings of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Ayyub al-Masri a "potentially devastating blow" to al-Qaida in Iraq.

But as in the past, al-Qaida in Iraq has proved resilient. Under al-Baghdadi's leadership, it has come roaring back stronger than it was before he took over.

The man now known as al-Baghdadi was born in Samarra, about 95 kilometers (60 miles) north of Baghdad, in 1971, according to a United Nations sanctions list. That would make him 42 or 43 years old.

Al-Baghdadi is a nom de guerre for a man identified as Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai. The U.S. is offering a $10 million reward for information leading to his death or capture.

He is believed to have been operating from inside Syria in recent months, though his current whereabouts aren't known. Iraqi Interior Ministry spokesman Saad Maan Ibrahim said authorities believe he was in Iraq's Salahuddin province, north of Baghdad, as recently as three weeks ago, but he moves around frequently so as not to be captured.

What little else that is known publicly about al-Baghdadi comes from a brief biography posted in July to online jihadist forums. Its claims could not be independently corroborated.

According to that account, al-Baghdadi is a married preacher who earned a doctorate from Baghdad's Islamic University, the Iraqi capital's main center for Sunni clerical scholarship. The biography linked him to several prominent tribes and said he comes from a religious family, according to a translation by the SITE Intelligence Group, which monitors extremist sites.

He rose to prominence as a proponent of the Salafi jihadi movement, which advocates "holy war" to bring about a strict, uncompromising version of Shariah law, in Samarra and the nearby Diyala province.

The biography linked him to Samarra's mosque of Imam Ahmed bin Hanbal, which according to one resident, speaking anonymously for fear of retribution, was a key hub for al-Qaida decision-making in 2005 and 2006.

Samarra, like Diyala a hotbed for al-Qaida activity, was the scene of the 2006 bombing of the Shiite al-Askari shrine. That attack was blamed on al-Qaida and set off years of retaliatory bloodshed between Sunni and Shiite extremists.

Al-Baghdadi's leadership of the Iraqi al-Qaida operation coincided with the final year and a half of the American military presence in Iraq. The U.S. withdrawal in December 2011 left Iraq with a precarious security vacuum that he was able to exploit.

"Al-Baghdadi has managed a remarkable recovery and re-growth in Iraq and expansion into Syria. In so doing, Baghdadi has become somewhat of a celebrity figure within the global jihadist community," said Charles Lister, an analyst at the Brookings Doha Center.

The group has kept up pressure on the Shiite-led government in Baghdad with frequent and coordinated barrages of car bombs and suicide bombs, pushing the country's violent death toll last year to the highest level since 2007, when the worst of Iraq's sectarian bloodletting began to subside.

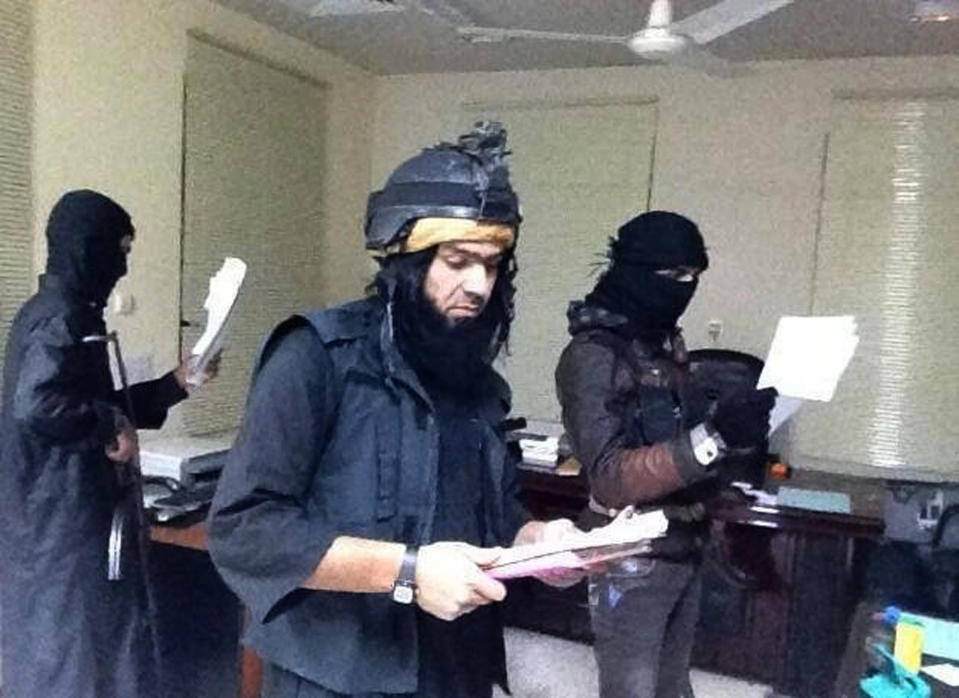

A series of prison breaks, including a complex, military-style assault on two Baghdad-area prisons in July that freed more than 500 inmates, has bolstered his group's ranks and raised its clout among jihadist sympathizers.

That notoriety only grew when his fighters seized control of the city of Fallujah and other parts of the vast western Anbar province in recent weeks.

His push into Syria has won him large numbers of foreign recruits, and is helped by "a slick and effective propaganda machine, which has had a truly global reach," according to Lister. Last year, he added "and the Levant" to the end of his group's name to reflect its cross-border ambitions.

But its muscling in on other Syrian rebel groups' territory has created divisions among the militant ranks. The Nusra Front, an al-Qaida-linked rebel group in Syria, bristled at the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant's unilateral announcement of a merger — effectively a hostile takeover — last year.

Abu Qatada, a radical preacher who was deported from Britain and faces terrorism charges in his native Jordan, is among those who have criticized ISIL's role in Syria. He warned last week that ISIL's fighters were "misled to fight a war that is not holy."

Many Syrians have been turned off by ISIL's strict and intensely sectarian interpretation of Islam, including brutal measures such as the beheading of captured government fighters and its focus on establishing an Islamic caliphate.

Al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahri has tried unsuccessfully to end the infighting but frictions between the ISIL and other Syrian rebel factions erupted into outright warfare in recent weeks. The London-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimates that more than 1,700 people have been killed in clashes between ISIL and other factions since Jan. 3.

It was that infighting that likely prompted al-Zawahiri to ultimately sever ties, setting up a potential fight over resources and influence.

"Any separation means a split in strength and resources between the rival wings," said Ibrahim, the Iraqi Interior Ministry spokesman. "This division between al-Zawahiri and al-Baghdadi is due to only conflicting personal ambitions between two people."

___

Associated Press writers Sameer N. Yacoub in Baghdad and Maamoun Youssef in Cairo contributed reporting.

___

Follow Adam Schreck on Twitter at www.twitter.com/adamschreck

Yahoo News

Yahoo News