Italy's crumbling infrastructure under scrutiny after bridge collapse

The collapse of a bridge in Genoa on Tuesday, which killed 39 people, is the latest symptom of Italy’s infrastructure woes. More than 2m homes across the country are unstable, according to figures from the national statistics agency, Istat, and more than 156 school ceilings have fallen in over the last five years.

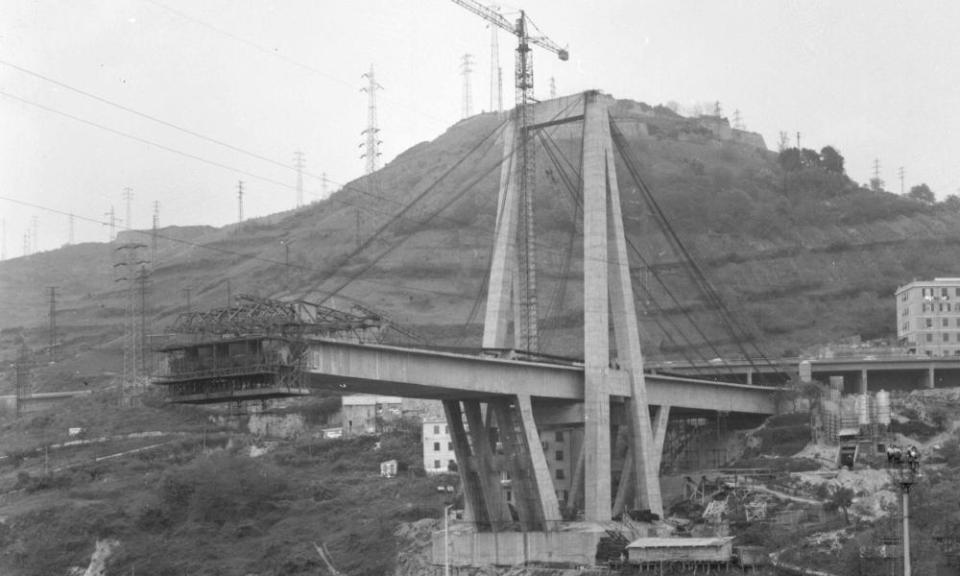

The Morandi Bridge, considered an engineering jewel when it was inaugurated in 1967, was the 12th bridge to have collapsed in Italy since 2004. Five of those were in the last five years.

Many of the problems can be traced back to the construction boom of the 1960s, when bridges, roads, buildings and schools were being built, often with weak or cheap material to increase profits, and ending up in the hands of the mafia.

“There’s no doubt that the building boom of the 1960s contributed to exacerbating the situation because so much was built then – everywhere and not always with adequate standards,” said Maurizio Carta, a professor of city planning at the University of Palermo.

“We built in fragile areas, along riverbeds, in areas prone to landslides, along cliffs, and in high-risk hydrogeological and seismic areas, not to mention near heavy infrastructure, which increases the risk for people living there – in essence, where they shouldn’t be living in the first place.”

That includes those living below the Morandi Bridge, who, as the mayor of Genoa has said, must now be evacuated because their homes are at risk. By contrast, there was no time to evacuate the residents of Messina province, in northern Sicily, before their homes were swept away by mudslides and floods in 2009. Those houses were built in a high-risk hydrogeological area subject to repeated landslides over the years. The tragedy left 37 people dead and 95 injured.

Buildings and roads in southern Italy are at higher risk, and experts agree this is no coincidence. Construction firms, many of which colluded with the mafia for decades, used “unfortified cement” – comprising a disproportionate amount of sand and water, and very little concrete. Profit for every pylon or kilometre of road was guaranteed, but over time these roads and bridges began to fall apart.

Of the 12 bridges to have collapsed in recent years, four were in Sicily, and two were the subject of subsequent investigations by district attorneys for construction using unfortified cement.

Dozens of bridges and tunnels are under investigation for the same reason in Calabria, the most recent on an exit near Germaneto from route 106, on which there have been several partial collapses.

“During core sampling analysis of tunnels and bridges, I have found cement blocks with a resistance three times weaker than the norm,” Nicola Gratteri, the anti-mafia chief prosecutor in Catanzaro, told the Guardian.

“These were public works completed by the ’Ndrangheta. Here in Calabria the mafia has controlled the building sector since the 1960s, and today the entire concrete business is under their control. The building sector is the second most profitable activity for the ’Ndrangheta after drug trafficking.”

In 1959 in Palermo, Vito Ciancimino, a mafia boss from the Corleonesi clan, became the head of public works. The wounds inflicted by the mafia run deep, visible even in the city’s architecture. Ciancimino ordered the demolition of splendid 19th-century villas, replacing them with grey and dreary low-cost constructions. This architectural period is remembered as the “sack of Palermo”.

“Over the years, those constructions built by the mafia begin to crumble, the support structures begin to fall apart,” said Carta. “The plaster crumbles and the topmost structures eventually collapse.”

According to a study conducted by Confartigianato, an association of Italian tradespeople and artisans, a fifth of Italian dwellings are in poor condition or are at risk of collapse, like the apartment building that fell apart on the night of 7 July 2017 in Torre Annunziata, near Naples, killing eight people.

However, unfortified cement is not the only cause of these disasters. There was no unfortified cement in the bridge that collapsed in Lecco in October 2016, killing a man driving home from work. And no mafia bosses were behind the construction of the bridge in Fossano, which crumbled in April 2017.

Approximately 300 bridges are at risk of collapse in Italy and all require a large amount of money for maintenance which, according to experts, may never solve their structural problems. The company that ran the Morandi Bridge, Autostrade per l’Italia, launched a €20m (£18m) public tender for safety repairs in May this year – the latest of a series of maintenance works carried out over the years.

According to the National Council for Research, much of the infrastructure built in Italy in the 1950s and 1960s is at risk due to its age. The materials used, such as reinforced concrete or pre-stressed concrete, have a lifespan of 50 to 60 years, experts have said.

In the country of the Colosseum, Roman aqueducts and 1,000-year-old churches, it seems paradoxical that 40-year-old structures are crumbling.

“We have used materials which are destined to deteriorate quickly, like those of the bridge in Genoa,” said Prof Antonio Bercich, of the University of Genoa, who warned of the risks associated with the Morandi Bridge two years ago. “Engineering experts in previous decades believed that reinforced concrete would have permitted the construction of miniature colosseums that would have lasted forever. But that’s not the way it turned out. There are structures from those years that should now be demolished.”

The Temple of Concordia, built in around 440BC, is considered one of the world’s best-preserved Greek temples. Located in Agrigento, western Sicily, it is just a few kilometres from a 4km bridge which was closed last year because it was at risk of collapse. The bridge was completed in 1970 by the engineer Riccardo Morandi.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News