How Italy has dodged a second wave - for now

Commuters and students with bulging backpacks step off the train platforms and walk briskly past bustling espresso bars, fashionable shoppes and trattorias laying tables for the day.

It feels – except for the fact everyone is wearing masks – like any other typical autumn back-to-school day in a mid-sized Italian city. Classes start Monday here in at Italy’s largest, oldest university in Bologna following an alternating weekly hybrid approach: half of pupils following the live stream online, the other half sitting in pre-selected seats in the classroom, where both students and professors must wear masks during lessons.

Much of Europe is struggling with what WHO officials this week warned was an “alarming” second wave of Covid-19. New lockdowns and restrictions are being considered for regions of Spain, France and the UK.

Italy, however, seems to have dodged – or at least delayed - the second wave bullet thus far. While the UK has seen new cases jump over 4000 a day, and France over 9,000, Italy’s new cases have been hovering between 1500-2000 a day (very few compared to the 30-40,000 cases Italy was seeing last spring), with around 100,000 people tested daily.

The chart below shows the progression of Italy's cases.

“In Italy we have not returned to the contagion levels of March like in other European countries but we have to be careful and not let our guard down,” said Walter Ricciardi, one of the Ministry of Health’s guiding scientific experts. Distancing, masks, and controlling clusters are key, Ricciardi said, along with encouraging flu vaccines and use of Italy’s contact tracing app “Immuni”.

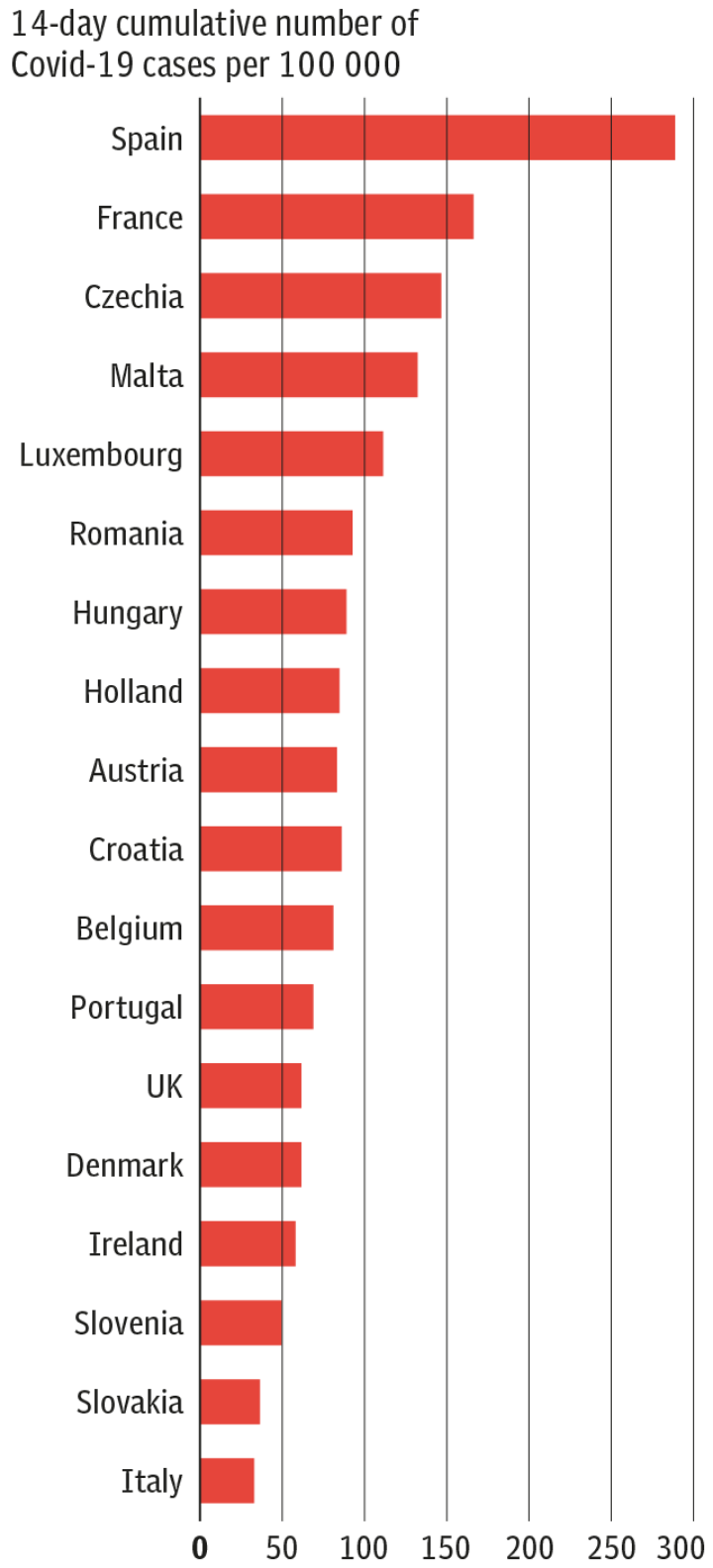

According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Italy ranks 14th in the list of EU countries for cases per 100,000 people in the last two weeks. Spain and France are at the top.

What did Italy do differently?

Italy kept its quarantine at 14 days, refusing to shorten it to 7 or 10 as other European countries did. But most importantly, Italy is using its testing capacity wisely, said Andrea Crisanti, a molecular parasitologist at Imperial College on secondment to the University of Padua credited with helping contain the virus in the Veneto region.

“Today, the active surveillance strategy we adopted in Veneto is being used country wide,” Crisanti told the Telegraph. “Every time we get a positive case, even asymptomatic, we test everybody who is part of the various family, social and work networks of that person. This is how all our clusters are now being handled.”

“By rapidly pinpointing new positives, with the help of health departments, we are intercepting new outbreaks by isolating all the closest contacts,” confirmed Raffaele Donini, Emilia Romagna regional health counsellor.

Unlike Spain, Italy did not court foreign tourists (there were noticeably fewer in popular spots like Venice and Florence) and clamped down on the party scene, controversially prohibiting dancing in nightclubs August 17. Soon after an outbreak was reported in Sardinia's Billionaire club.

Former premier Silvio Berlusconi, above, was also infected after holidaying in Sardinia. After a 10-day recovery in a Milan hospital, the 83-year-old media tycoon went home Monday, boasting about how high his viral load had been while urging everyone to wear masks.

There is widespread civic adhesion to mask-wearing in Italy, a notable difference with other European countries. Fear is a factor, too. Italians were the first in Europe to experience the coronavirus nightmare and subsequent lockdown that blocked them in their home districts for months. The grim death bulletins and televised images from inside overwhelmed hospitals and morgues had a chilling psychological impact.

“The shock of being the first European country to get hit by the pandemic and experience an extended lockdown has not worn off," said Erik Jones, professor of European Studies with Johns Hopkins University in Bologna. “Italians are wary of what a second wave might bring and eager to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

While it may have slowed contagion, the lockdown hangover has wreaked havoc on Italy’s economy. GDP plunged 13 per cent in the second quarter and nearly half of Italians polled by YouGov - Kantar reported their financial situation has worsened.

“Even despite the €209 billion influx of recovery fund money, this economic crisis is not going to be easy to shake off,” said Mr Jones.

A second wave may still arrive, however. With school just starting, it is still early for health experts to detect community transmission quietly spreading as large groups start gathering again.

“We are in an unstable equilibrium with two forces acting in opposite directions,” Crisanti explained. “One the one hand, we are giving the virus the opportunity to transmit when we go back to work and school, the force pulling in the other direction is our behaviour, so we need to now be a little more strict about masks, social distancing and testing to keep that equilibrium.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News