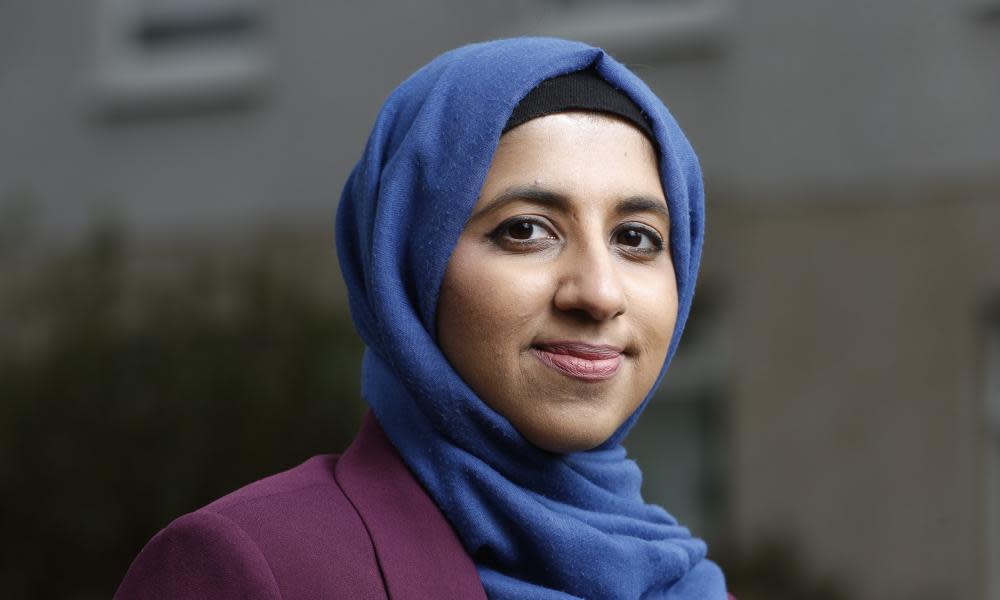

'I've grown tenfold': Zara Mohammed on her whirlwind start as MCB head

In the past few weeks Zara Mohammed has been living, breathing and even dreaming about her new role as the first female and youngest ever head of the Muslim Council of Britain. “My mind doesn’t stop. There are times when I need to go see the ducks in my local park, just to take a break.”

Apart from the responsibilities of leading the UK’s foremost Muslim umbrella group, with more than 500 affiliates, Mohammed, 29, has also experienced an “ongoing media blitz” – including a now notorious interview on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour. “I didn’t really expect the extent of this celebrity, if you can call it that,” she says.

But “what’s been really lovely is the support, encouragement and positivity, especially from young women and women of all colours, all faiths. It’s been a whirlwind but it’s also been challenging. You use the stress to power you forward. I have grown tenfold.”

Four days into the role, the BBC posted online a clip from an interview with Mohammed by Emma Barnett on Woman’s Hour concerning female imams. The corporation received hundreds of complaints, and an open letter signed by 100 public figures including the Tory peer Sayeeda Warsi claimed the line of questioning reinforced “damaging and prejudicial tropes” about Islam and Muslim women.

“I have to admit I was really taken aback [by the interview]. It was particularly hostile and aggressive,” says Mohammed. She felt like she was having “an out of body experience” as she went through what “felt like an interrogation if I’m honest. I have no problem with bold conversations or being challenged, but [this was] again about stereotyping us and vilifying us and not allowing us to define who we are.”

She says the open letter “highlighted the broader issue of Muslim women being sick of being represented in a certain way. The media has stigmatised Muslim women and continued to perpetuate these very negative stereotypes. The letter [was saying] ‘we’ve had enough of this’.”

On Barnett’s question about female imams, Mohammed says: “It shows an ignorance [of] religious hierarchy in Islam. Muslim women do not lead men in prayer. But the imam is a procedural role. What’s really important is the role of Muslim women in leadership roles, including scholarship, over 1,500 years, shaping and influencing our traditions in faith.”

A second encounter also generated headlines – this time a meeting with Penny Mordaunt, the paymaster general, that contravened the government’s longstanding policy of not engaging with the MCB.

“It’s not clear to us why they will not engage,” says Mohammed. “Of course there’s a conversation to be had, and a relationship, because [government] policies are impacting our communities – look at Covid, the perfect example. Why wouldn’t they want to talk to us about these things? I would welcome that engagement, and I do think the government should grow up. Let’s not get stuck in the past.”

In response to a question from the Guardian about the reasons for its policy of non-engagement with the MCB, a government spokesperson declined to comment.

Mohammed, the eldest of four siblings, grew up in Glasgow and attended a state school that she says was “pretty much all white”. She studied law and politics at Strathclyde University, followed by a master’s degree in human rights law.

“In my second year [at university] I put my headscarf on. I was affirming my identity as someone confident to be Muslim. And that’s when I really began to face differential treatment.”

She has felt vulnerable, especially on public transport, she has witnessed and challenged abuse, and she believes some of her job applications have been rejected because of her name.

Now she advises companies on training and development, but that has been put on hold since being elected to the voluntary, unpaid two-year term as MCB secretary general. “I didn’t expect [the role] to change my life so much,” she says.

Her mother always worked, even when Mohammed and her siblings were young. “She was pretty headstrong and resolute, she wanted to do stuff for herself. She’s strong and confident, she feeds all the neighbours, she’s the family support hotline – even now she makes sure I’m eating. Both my parents [urged me to] focus on my career and be financially independent. I got a lot of investment and encouragement.”

Despite such support and her own natural ebullience, Mohammed says: “Like all women I suffer from impostor syndrome. I’ve always had crippling self-doubt. I will come up with 100 reasons why not to put myself forward, that maybe someone else – a man – is better.”

Nevertheless, she won the election decisively, by 107 votes to 60, against a male opponent, Ajmal Masroor, an imam and teacher. She has set three priorities, saying she has an “amazing opportunity to make a difference”.

The first is inclusion and diversity. “I want to create opportunities for more women, young people, and underrepresented communities. I really want to be a champion for Muslim women. You always start with yourself before telling everybody else what they have to do. I’ve appointed more women to the [MCB’s] national council, we’re getting more women’s organisations to affiliate, and there’s going to be a change in the landscape of Muslim women within our organisation.”

Young people need a louder voice, and the MCB must become more representative of UK Muslim communities, she says. “We have probably one of the most diverse and Muslim communities in the world at our doorstep – Malaysians, Somalis, mixed-race people, converts. We do need to do better [at representing them].”

Tackling Islamophobia is second on her list. “I’m going to be challenging the narrative of negative stereotypes and tropes, and the idea that Muslim communities are one homogenous block.”

The response to Covid is third on her list, “though it’s always number one really,” she says. Muslim communities have seen a “spike in mental health issues, a devastating economic impact, even mosques being unable to sustain themselves because they’re not getting the funding they normally get from the members. We need to build strategies to help us face that.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News