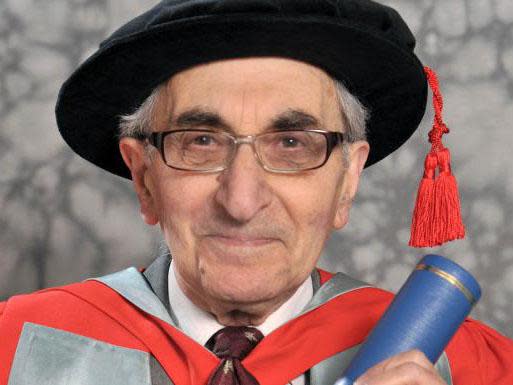

Jack Hayward: Political scientist whose scholarship on France won him the country’s highest civilian honour

The political scientist Professor Jack Hayward, who has died aged 86, came to prominence in the so-called Oxford insurgency in 1975 which overthrew the “old guard of senior professors which had long dominated the executive of the Political Studies Association (PSA) – a not-for-profit set up in 1950 with funding from Unesco.

At its annual conference at Oxford the retiring executive expected re-election. But tapping into a groundswell of discontent a slate of young academics (most of whom later became prominent members of the profession) offered themselves for election on a reform platform. A contested election was unheard of, leaving some appalled at such divisive conduct.

The group, to their surprise, won easily. But they had made no plans and hurriedly chose Hayward, the only professor among them, as chairman. He chastised those who said it was a coup, pointing out that an election was not a coup. Many of the senior figures were scarcely seen again at conferences. A new generation had taken over. The new team inaugurated a series of reforms that transformed the work of the PSA, greatly expanding membership and extending the range of activities and services.

At the universities of Hull and Oxford, Hayward was a successful builder of institutions: at the first of politics and the second of European studies. He was also the latest in a long and distinguished group of British students of French history, society and politics. In 1996 the quality of his work on France over some 30 years was recognised by France with a Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur. In 2011 he won the PSA’s Isaiah Berlin award.

If he had a hero it was the charismatic Sammy Finer, who appointed him to a post at Keele University in 1963. Finer was a solitary scholar and Hayward at the end of his career sometimes wondered if his profession’s concentration on collaborative research had gone too far and the talents of the individual scholar subsumed in collective projects. (Paradoxically, he was himself an indefatigable member of committees, workshops and research groups). He brought to fruition Finer’s three-volume History of Government from the Earliest Times (OUP, 1997) covering 5,000 years.

Finer had died four years earlier with the work incomplete. It was a remarkably generous act on Hayward’s part but he regarded it as paying an intellectual debt. Hayward was born in 1931 in the International Concession in Shanghai.

His first 14 years were spent as a British boy of Jewish upbringing in China, including three and a half in a Japanese internment camp. In 1946 his family returned to England and he went to the London School of Economics in 1949 to study government. At LSE his tutors included Ralph Miliband, father of David and Ed Miliband, and, crucially, William Pickles who fired his interest in French politics. He remained at LSE to complete his doctorate under Michael Oakeshott who contributed little beyond correcting his punctuation.

After completing his PhD and national service in the RAF, Hayward spent four years as a politics lecturer at Sheffield University, before moving to Keele. This was a lively department and a number of colleagues later achieved positions of eminence in the profession.

At Keele, he produced his first book, Private Interests and Public Policy (1966) a study of the Economic and Social Council of France. This prompted some wider interest because Harold Wilson’s Labour government was interested in French economic planning and cooperation between interest groups and government.

Relations between state and industry in France remained an interest for Hayward and he edited or co-authored a number of books on the subject. He complained that the British did not understand how the French system worked and this led to naive institutional borrowings; hence his justification for comparative research.

He argued that the weakness of Whitehall vis-a-vis business and the trade unions led to “pluralistic stagnation”. In 1973 he published The One and Indivisible French Republic; the title was an ironic challenge to the revolution’s claim to have established a sense of national unity.

In the same year he was appointed a professor of politics at Hull. He recruited and, more significantly, retained a number of outstanding scholars. In the Research Assessment Exercises for Higher Education in the 1990s, the politics department, alone across the university, was rated outstanding. Even when he ceased being head of the department he was still the senior figure, one to whom colleagues looked for personal and professional guidance, academic promotion, and a supportive word on their behalf with the university managers.

Having turned 60 he was, like many academics of his age, planning for early retirement. But in January 1993 he moved to Oxford as professor of politics and director of the European Studies Institute. He extended the interests of the institute to take account of developments in Eastern Europe and supervised a number of doctoral students.

Although he was a fellow of St Antony’s College, his family home remained in Hull which he found a more congenial place for living. Oxford provided the opportunity to work with his friend and fellow don Vincent Wright and they wrote The Core Executive in France (2002), although Wright had died in 1999.

Then he and Anand Menon dedicated a festschrift to him entitled Governing Europe in 2003. He wrote regularly on French Presidential elections and edited De Gaulle to Mitterand: Presidential Power in France. His collaborative volume on Industrial Enterprise and European Integration (1995) explored the different ways in which national firms in Britain, France, Germany and Italy adapted to the pressures of globalisation and the European Community. His concern with the EU’s unification by stealth and the need to carry the public was covered in his The Crisis of Representation in Europe (1995) and Elitism, Populism and European Politics (1996).

Forty years after his childhood internment the British government announced a scheme to compensate those who suffered internment or had been prisoners of war at the hands of the Japanese in the Second World War and Hayward was invited to apply. He was furious when he (among others) was informed that he did not qualify because, in his words, he was considered “not British enough”.

He mounted a campaign and convinced the ombudsman that that the scheme’s eligibility criteria were inconsistent and discriminatory. Although he received an apology and compensation from the government he remained angry on behalf of those who were denied what he regarded as justice. Hayward wrote easily and well, despatched business quickly and did not agonise over his decisions.

As a committee chairman he was good at bringing key issues to the fore and reaching a conclusion. When he edited the journal Political Studies between 1987 and 1993 he maintained its reputation and resisted demands from various lobbies for preferential access. In a famous essay he described British political science as “a self-deprecating discipline”, at times energised by “homeopathic doses of American political science” and with “the capacity to offer a little insight and almost no foresight”.

When he left Oxford in 1998 he returned to a position as research professor in the politics department at Hull. By the time of his retirement he had become an elder statesman in the profession, representing it on various national and international bodies. Vice-chancellors sought his views when they were filling chairs in politics. He combined all this activity with numerous visiting professorships in Paris and a steady output of edited books and articles. He was a prime mover and co-editor of the British Academy’s The British Study of Politics in the 20th Century (2002) to celebrate the academy’s centenary. He was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1990 and for some years chaired its politics section. He is survived by his wife Margaret, a son Alan, a daughter Clare, and four grandchildren.

Professor Jack Hayward, political scientist, born 18 August 1931, died 8 December 2017

Yahoo News

Yahoo News