Jeremy Corbyn's intervention on terror is tasteless and wrong

Election campaigning resumes today in defiance of the terrorist threat. That is a good thing: Britain is resilient. What is less good is that Jeremy Corbyn appears unbowed by questions of taste. In defiance of common sense, he will give a foreign policy speech today in which he will suggest that there is a link between Britain’s foreign policy and terror attacks on UK citizens. This is called “blaming the victim”. It is a crass misdirection away from the only person responsible for the actions of Salman Abedi – Abedi himself.

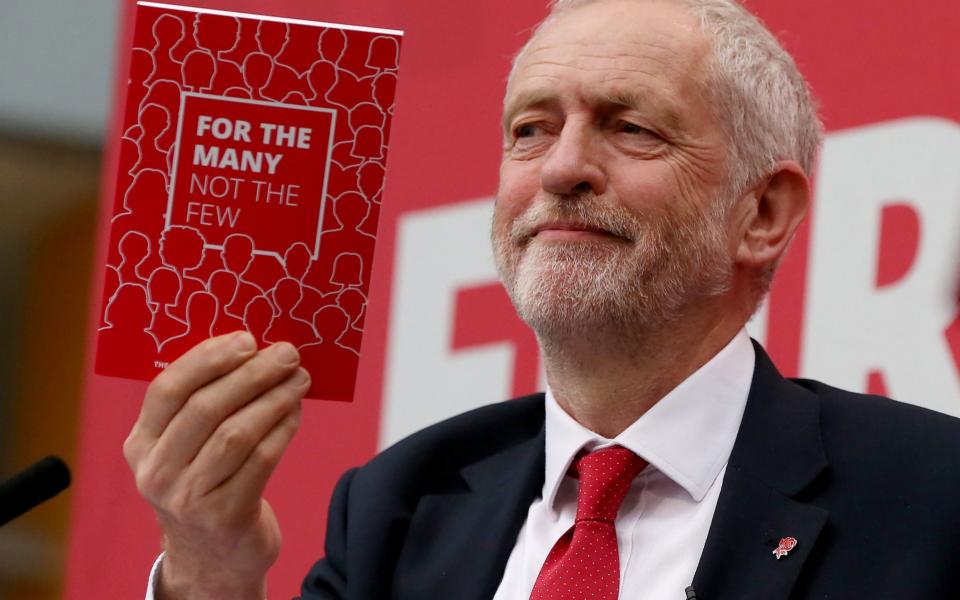

How did such an inexperienced, extreme, obscure backbencher become leader of the opposition?

Of course, Mr Corbyn is saying what he has been saying for years: first in outspoken terms as a backbencher and later in more careful language as leader of his party. On May 12, he gave a speech at Chatham House in which he said the war on terror had been a failure, had reduced security and “made the world a more dangerous place”. Some voters may well have agreed with him. But the difference between May 12 and today is that a major terror attack has occurred in between. His words, at the very least in their timing, are staggeringly insensitive.

They are also inaccurate. What had Britain done to Abedi? It offered his family refuge from the Gaddafi regime, much as it does to countless other Muslims fleeing terror. To imply that the country that gave the Abedis a place to hide somehow invited the rage of their son is absolutely ridiculous.

Mr Corbyn will state that his view of foreign policy in “no way reduces the guilt of those who attack our children”. But many will infer that he is spreading that guilt to the West. This fits with Mr Corbyn’s lifetime spent accusing the West of illegal and unethical actions. Indeed, the suggestion that Mr Corbyn is a pacifist is sometimes belied by his association with organisations that are the opposite, including Sinn Fein. Aside from appearing on Iranian sponsored TV, where he labelled the death of Osama bin Laden as a “tragedy”, Mr Corbyn once also referred to Hamas and Hizbollah as “friends”. He later expressed regret for that, explaining that it was “inclusive language I used which, with hindsight, I would rather not have used.”

Is Mr Corbyn simply a clumsy speaker? No. Today’s remarks are scripted: he will tell us what he truly believes. And what he believes is not only wrong but a dangerous distraction. Obsessing about the West’s historic guilt overlooks what it could be doing right now to improve security. “An informed understanding of the causes of terrorism,” Mr Corbyn will say, “is an essential part of an effective response.” We agree. But that means asking why it was that on five separate occasions warnings about Abedi were made and yet nothing was done. It means reopening the question of how to deal with the Middle East returnees: observation, detention or deportation. It means challenging the liberal consensus on multiculturalism and immigration, acknowledging that taking so many people, without proper requirement to integrate, can hurt a country. It means asking the Europeans to rethink their border policy. Mr Corbyn’s fans may dream of a borderless world, but Europe is being exploited by people traffickers and terrorists.

Moreover, Mr Corbyn’s speech distracts from the locus of legitimate moral outrage: Abedi himself. The Labour leader is not alone in doing this. Elsewhere, anger at the leaking of sensitive material to the US media, for instance, is justified – but a misdirection, too. Then there is the spurious claim that there is little difference between Islamist terrorists and Right-wing commentators who call for a reckoning with Islamism: the first, of course, have actually killed someone, while the latter have not. Perhaps it serves a psychological need to find living Westerners to be angry at because the culprit is dead. But it is the killer who really matters, and attempts to talk about anything else risk testing the public’s patience.

Political debate about terrorism is inevitable. Policy has an impact, and we would be very surprised if discussion did not feature heavily in this coming campaign. But when a leader makes an intervention this ill-conceived, they can hardly be surprised by the visceral reaction that follows. Nor can they be surprised if it prompts a revisiting of that politician’s record. In this election, Mr Corbyn is himself one of the major issues of debate. How did such an inexperienced, extreme, obscure backbencher become leader of the opposition?

Mr Corbyn has been on the wrong side of most arguments that he has injected himself into. He has displayed not just a stunning naivete but a moral blindness. This speech is yet another betrayal of generations of moderate Labour voters. We expect many of them to take note of his words, consider the flawed logic within, and conclude that this is one election when Labour is simply unelectable.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News