Will Jeremy Hunt foot the bill for NHS staffing? The signs aren’t promising

“There’s a gap today that no locum filled, so I am carrying both bleeps and doing the work of two people.” That recent tweet, by a children’s doctor, is one of many examples posted on social media by medics illustrating how NHS staff shortages affect them, patients, the smooth running of important services – and, sometimes, the safety of those who are receiving care.

It is a concern shared by every organisation that represents frontline staff, by regulators such as the Care Quality Commission (CQC), and by NHS England, the body that oversees the service. Just as one example, in January the CQC reported that an inspection it had undertaken of Colchester hospital in Essex found patients were missing out on meals because there were too few staff on duty to feed them. Some patients were wearing dirty dressings, and others did not have their call bells answered promptly, for the same reason.

In a letter to the trust that runs the hospital, it said: “All wards’ actual staffing levels and skill mix meant staff were often overstretched. All staff we spoke with expressed concern about the impact on patient care and personal wellbeing.

“Some staff we spoke to were tearful, reported feeling exhausted and concerned that they were unable to care for patients well enough to keep them safe.”

Lack of staff can also mean cancelled operations. In 2018-19 in England 10,900 operations were cancelled due to lack of staff. Last year that had almost trebled to 30,000, freedom of information requests by Labour to hospital trusts disclosed in December.

The acute staff shortages that have affected the NHS’s ability to perform its vital role have been evident, and causing concern, for years. Countless reports have documented their impacts, such as a hospital having to limit the number of cancer patients who could receive chemotherapy because it had too few specialist nurses to meet demand.

One of the most hard-hitting, well-evidenced and comprehensive of the many reports was published last July by the Commons health and social care select committee. It warned that the NHS and social care were facing “the greatest workforce crisis in their history, compounded by the absence of a credible government strategy to tackle the situation”.

It said that “persistent understaffing poses a serious risk to staff and patient safety in routine and emergency care”.

Related: NHS operations cancelled in England due to staff shortages double in three years

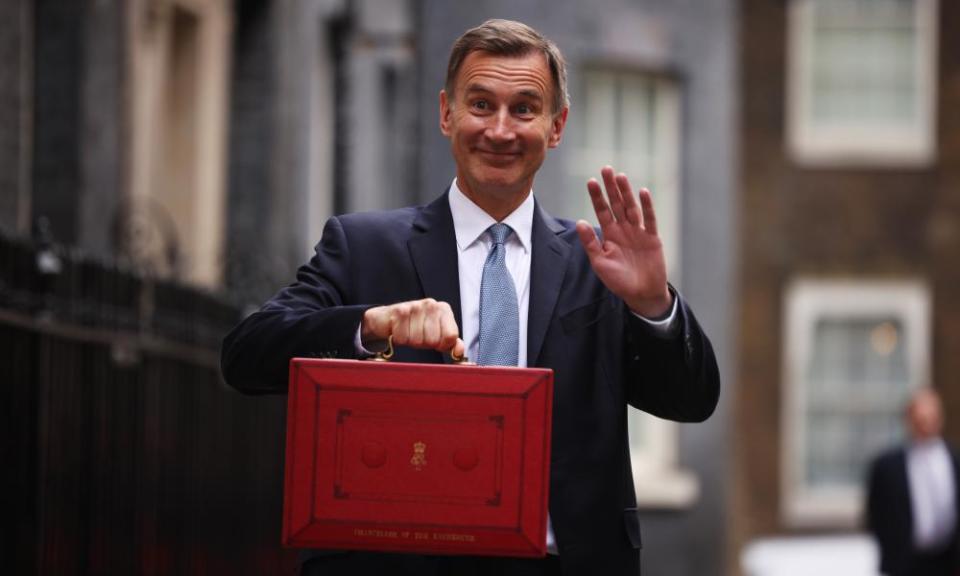

The committee was chaired by Jeremy Hunt, the longest-serving health secretary in history. He underlined his commitment to giving the NHS the staff it needs by arguing for not just a big expansion in the number of homegrown doctors, nurses and other health professionals but also publication of regular updates on how many of each the service needed.

However, three months later he became the chancellor of the exchequer – first under Liz Truss and then Rishi Sunak – and since then has said much less about this subject.

Even with NHS England’s much-delayed long-term workforce plan now on his desk, the signs are not promising that he will seize the moment and rubber-stamp the huge rises in personnel envisaged and agree to foot the bill.

“Jeremy’s sincere in his commitment to the NHS. But he’s also a politician. And I think those two things are in conflict at the moment over the workforce plan,” said one senior NHS official.

As health secretary, Hunt often urged the NHS to learn from the priority the airline industry gives to passenger safety. As chancellor, he has the opportunity to cement his place in NHS history as the minister who enabled it to finally put risky, wasteful and exhausting understaffing behind it. The alternative is to be seen as the minister who forced the nation’s most vital service to continue flying with too few crew.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News