John Leech: the cartoonist who gave us Christmas past

Scrooge sits by the fire, warming his hands on its meagre heat. To his left is the ghost of Jacob Marley, the chains that encircle him a testament to his life of cold-hearted avarice. Between them is a candle – its cold, cruel light illuminating one of the best-known and most beloved stories of its (and our) time: Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

The artist who illustrated the scene was John Leech. A huge star in his time, Leech’s fame has receded like many of his Victorian contemporaries. But a new film about the writing of Dickens’ masterpiece, which features Simon Callow as the cartoonist and book illustrator, has brought Leech back like a ghost of cartoons past.

Although Dickens is often credited with inventing the modern idea of Christmas, Leech should certainly take some of the credit (or blame). It was A Christmas Carol, and its vivid illustrations, which cemented in the public’s mind the idea that it was wrong to work on Christmas Day – something that lead to the Bank Holidays Act.

At the time, Dickens was still in his early 30s and was in a bit of an early-career slump. His previous novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, had not been the success to which Dickens had become accustomed. Dickens needed a hit. With this in mind, he knew the choice of illustrator would be a key factor in its popularity. It was little surprise that he turned to Leech.

Born in 1817, John Leech was already being called a genius at an early age. It was with the new publication, Punch magazine, that he found his spiritual home. Launched in 1841, the magazine quickly shook off pretensions to radicalism and found its niche in a more respectable form.

Leech became a significant figure in Victorian society and culture, in some ways embodying the recent shift in taste in caricatures and journalism in general. The previous generation of visual satirists, personified by James Gillray, delighted in grotesque, scurrilous and often scatological illustrations, which even today can shock in the ferocity of their attacks on public figures.

Leech’s work, along with that of his fellow Punch artists, was gentler and designed not to offend the sensibilities of the magazine’s readers. That is not to say his work was toothless – far from it – but his targets were less likely to be individuals and more likely to be issues such as poverty. It was probably this element of his work that attracted Dickens.

As strange as it now may seem, Dickens’ publishers were less than enthusiastic. The novelist was in debt and they didn’t see A Christmas Carol as the way to turn this situation around. But Dickens persevered and with John Leech crafted a tale that more than made up in impact what it lacked in length.

Popular imagination

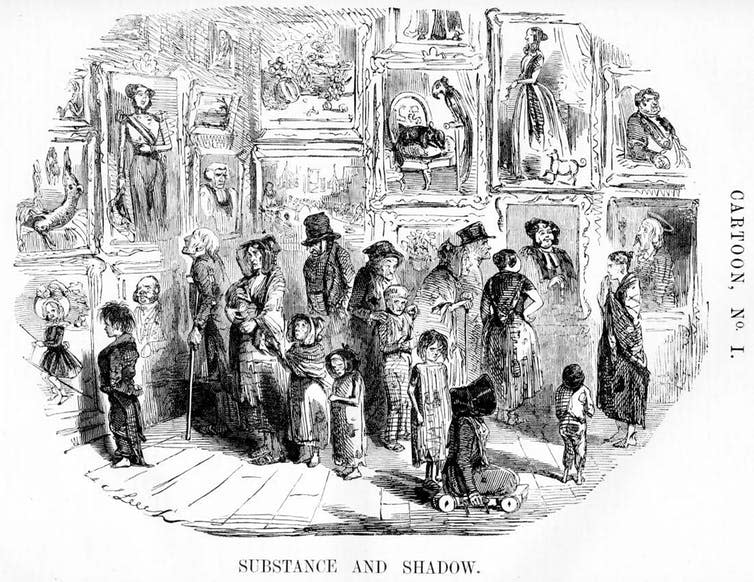

Leech can lay claim to have drawn the world’s first political cartoon. In 1843 – the very same year that Dickens published his Christmas classic – an exhibition of frescos was being held at Westminster, something that Punch thought inappropriate when many who were living in the same district were starving.

The exhibition featured cartoons in the original sense of the word – artists’ preliminary drawings – and was considered a worthy subject of attack by the magazine. Leech, then just 25, drew Substance and Shadow under the heading Cartoon No. 1.

It is a striking image, juxtaposing the grand setting of Westminster Hall with the dishevelled poor looking forlornly on. There is a definite feel of Dickens’ abhorrence to social injustice about this, and much of Leech’s later work. Soon, after all, the illustrations in Punch were being called cartoons, and their artists cartoonists.

Leech went on to further success and immense popularity. His work on the Crimean War remains a classic of political cartooning – it not only reflected, but actually influenced the news agenda; his friend, the novelist William Makepiece Thackeray going so far as to claim that the “popularity of Punch is perhaps owning more to John Leech that to any other man”. He could count among his admirers the likes of the artist John Everett Millais and the prime minister, William Gladstone.

More than 20 years after his death at just 47 in 1864, a collection of his work, Sketches of Life and Character, sold 140,000 copies. Perhaps most significantly, it has been claimed that it was Leech “who made the public look first at the pictures” – something that remains true today for cartoonists as diverse as The Guardian’s Steve Bell and the Daily Telegraph’s Matt.

While many other artists have illustrated editions of A Christmas Carol over the years, Leech’s work on the original has given him the right to claim that it was not just Dickens who was the man who invented Christmas.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

James Whitworth does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News