Juliet Stevenson: ‘As an older woman, you feel vulnerable just going on camera’

So much of life is about ‘trying not to’,” says Juliet Stevenson. “We try not to cry when we’re upset. We try not to show fear when we’re scared. We try not to shout when we’re angry, especially as women. We are encouraged to sit on it, internalise it. If we don’t, we’re ‘strident’, ‘nagging’, ‘bossy’.”

But, talking on the phone from her home on the Suffolk coast, the 64-year-old actor says she is often annoyed to see the opposite happen on stage or screen. “Actors are often far too quick to express anger,” she muses. “In real life, somebody shouting in public is a real, stop-and-stare event. It’s rare. The kind of acting I admire usually deals with the internal struggle.”

It’s a struggle Stevenson portrays with steely restraint in ITV’s new crime drama, The Long Call. Based on the novel by Anne Cleeves (who also created Vera), the four-part series finds Detective Inspector Matthew Venn (Ben Aldridge) investigating a murder linked to the fictionalised fundamentalist Christian community in which he was raised and by which, as a gay man, he was rejected.

Stevenson plays his mother, Dorothy, who she explains “has lost all contact with her son since he was 18. She chose her god over her child, like Abraham sacrificing Isaac on the mountaintop. He hasn’t recovered from Dorothy choosing her faith over him. She has not recovered from his decision to walk away from that faith. It feels like a test to her… although I found her very hard to understand when I first read the script.”

She says it would have been easy to play Dorothy as a cold-hearted monster. But watching a documentary about the Christian movement the Plymouth Brethren helped her understand the pressures on women in those communities. “The Brethren describe themselves as an egalitarian society, but the men and women within it are very far from equal. Women cook, clean and raise children. The men go off and make money and make decisions. The women in those communities are not encouraged to express their feelings.”

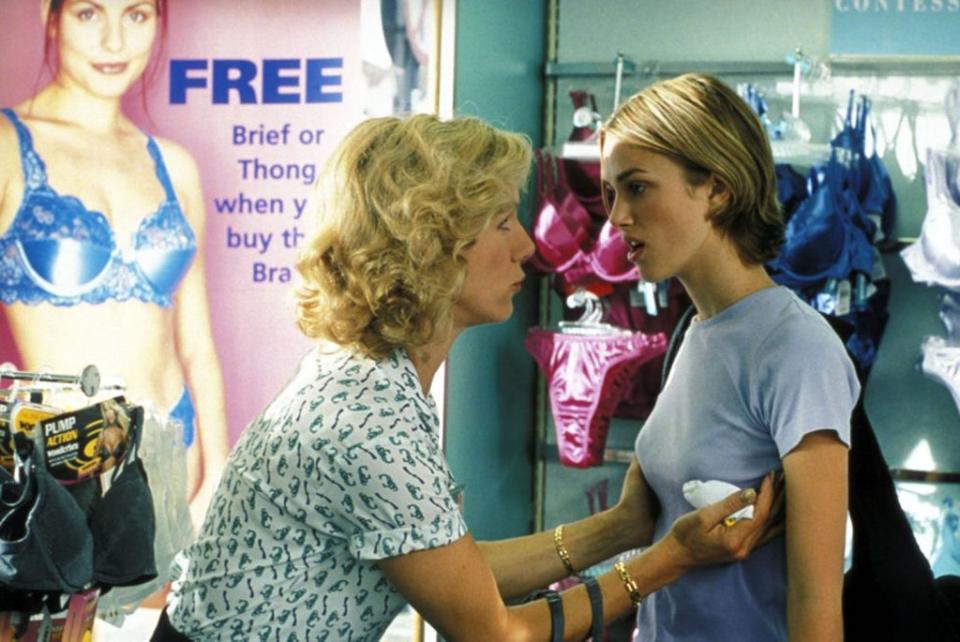

Stevenson, who is best known for roles including the grieving cellist in Truly Madly Deeply (1991) and the brittle Essex mum in Bend it like Beckham (2002), had a very different experience of the faith growing up. She says that from the age of nine she was sent to a boarding school, where a degree of emotional reserve was a required survival skill and religion was a grim duty. “We trudged to church every Sunday in a long crocodile, dressed in a ridiculous uniform. Services were long and boring: not conducive to enjoying religion. I very quickly dropped it when I was about 12 because it didn’t make any sense to me.”

Funnily enough, she made her first big splash as a novice nun – Isabella in a 1984 production of Measure for Measure with the Royal Shakespeare Company. Back then, RSC’s wardrobe department made her a rather sultry bride of Christ, dressing her in a plunging chiffon gown. But for The Long Call she was required to dress in the “bland and baggy, desexualising” garb, which she admits she found “very challenging”.

On set, she says, “we all laughed about the awful cardigans and headscarves. But of course we all care what we look like. As an older woman, you feel very vulnerable. You feel vulnerable just going on camera.”

Stevenson’s voice in person is so perfectly self-possessed that I find it hard to imagine her feeling such anxieties. Like many of my friends, I downloaded her old audiobook recordings of classics by Jane Austen and George Eliot to help soothe me through lockdown. In a world unmoored, her intelligent reading offered a grounded balance of dry wit and steady maternal wisdom.

That steadiness was shaken last November when Stevenson’s stepson, Tomo Brody, died suddenly aged 37. Five months later she told The Guardian that the loss had left her feeling like “we’d fallen down some rabbit hole and everything was just wrong”. Today she says: “We lost a beloved person. And there was so much loss anyway. We lost certainty in the world. We didn’t know if we would ever be the same again.”

She thinks the self-sufficiency I hear in her audiobook readings is probably a product of her nomadic childhood, moving from army base to army base. She’s a thinker and a coper. But, as a tomboy who has always struggled with performative femininity, she says: “I’ve never had huge confidence about how I project my appearance onto the world. I felt as though I was the only person questioning these things until I moved to London and began reading about feminism in the Seventies.”

Playing Rosalind in Shakespeare’s “dangerous” As You Like It at the RSC, a company with which she appeared a great deal in the late Seventies and Eighties, was also a watershed moment in Stevenson’s thinking about gender. Acting opposite Fiona Shaw’s Celia – who was part of the “new wave” of actors emerging from Rada with Stevenson at the time – she relished the ways in which the play questioned gender stereotypes and revelled in “the greatest female friendship in all of Shakespeare”. The role had such a powerful effect on Stevenson that she would later name her daughter Rosalind.

But, she assures, “I was never a radical. You can’t be too radical in this profession because you need to relate to ordinary people. And I’ve always had a very uneasy relationship with dressing up and red carpets, that whole side of the industry. I can tie myself in needless knots of those insecurities.” When her agent sent her out to Hollywood in the early Nineties to audition for a part in True Lies, she made it as far as the parking lot before turning her rental car round and coming home. The whole schmoozing-around-the-swimming-pool scene wasn’t her cuppa.

Stevenson has been much more content in the UK and is “deeply proud” to have been a mainstay of British films such as 2002’s Bend It Like Beckham. “That was such an important film,” she says. “It totally changed the perception of women in sport. My son is football mad, and we watch the women’s team together. Rooting for change is always more successful if you can do it with humour.”

More recently, she’s been delighted to play Sara Pascoe’s mother in the comedian’s 2020 sitcom Out of Her Mind. “I had a hoot filming the scenes in which my character is jogging while swigging white wine,” she says. “It’s so wonderful we’re finally getting to see so many comedies written by and starring women. Sara Pascoe is such a clear, challenging writer. So quirky, deliciously true, very funny about women’s strengths and frailties.”

Normally, Stevenson tells me, she finds that “acting is a liberation from the pressure of who to be in my own skin”. But she has found the experience of being shot with high-definition cameras “very brutal”. She says: “When I started out, directors of photography were all about lighting faces to make them appealing. That has all gone. Directors now want their lighting to stand out as individualistic. There is a lot of handheld stuff, with cameras just in your face. Not great for your vanity! Add in Dorothy’s headscarf and long grey wig and no make-up… well, when I saw some of the footage I thought: ‘I do look really grim!’” I can hear her wincing. “But it would have been more embarrassing if vanity had gotten the better of me. I hate it when you see actors on screen wearing make-up in situations where it would be absurd for them to have any, like when they’re pretending to be in a 19th-century prison or something.”

On the flip side, Stevenson says it was “a revelation” working with a female director of photography (DoP) for the first time on The Long Call. “I’ve worked with so many wonderful male DoPs and cameramen in my career. I’m not saying they’ve all made me feel objectified, not at all. But it was wonderful to be liberated from the male gaze. It made me realise how, subconsciously, I’ve always been so aware of what I’m doing with my face, of the expectations that other people have of my face. With a female DoP I was freed up to focus purely on the inner life of my character.”

As an open-minded liberal, Stevenson says she wants to be respectful in any discussion of the Brethren. But she concedes: “I find it very hard to accept the idea that we are supposed to be tolerant of any religion which seeks to lower the status of women. That their talents and ideas and identities are suppressed. That they must look the way men want. Why do we have to respect that, when in any other framework we can call that abuse?”

She sees parallels between the way the Brethren and the Taliban oppress women. “What we are seeing in Afghanistan is unbearable. It’s like watching the American evacuation of Hanoi in the Seventies. Seeing those people left at the airport feels like such a savage betrayal. I see Biden and Johnson saying: ‘This is what we had to do.’ Is it really? How have we not learned from history?”

Acting is a liberation from the pressure of who to be in my own skin

Stevenson is equally exercised by the Brethren’s homophobia. The Long Call is the first primetime ITV crime drama to feature a gay, male hero, played by a gay actor. Detective Venn is seen kissing his husband in the film’s opening scenes, and author Ann Cleeves has confidence that viewers will embrace the couple.

Stevenson finds it frustrating that “so often, film and television are a couple of beats behind the culture on these subjects”. But she says that the legalisation of gay marriage has made her decide to marry her partner of 28 years, anthropologist Hugh Brody.

“I grew up seeing marriage as a very constricting and confining institution for women. I could sense my mother’s frustration with it. I could sense the inequalities in it. Being an army wife is no picnic,” she says. “But the institution has been revolutionised by the inclusion of same-sex couples in a way that makes it much more attractive. Now I’m happy to tell the world, with my whole heart, this is my love.”

‘The Long Call’ premieres on ITV on Monday 25 October

Read More

Louis Theroux: ‘Straight white men like me have been monopolising the conversation’

Blake Harrison: ‘I’m surprised The Inbetweeners is still being watched now’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News