What we know about how political parties use Facebook advertising – and what we don't

Over the past five years, Facebook has exploded as a site for political advertising and election campaigning. Donald Trump, Jeremy Corbyn and Angela Merkel have all used it to promote their ideas. Yet despite the increasing prominence of Facebook, we currently know very little about how much political parties actually spend on the platform.

In a recent paper published in Political Quarterly, we looked in detail at the use of Facebook in election campaigns, using data from the UK. We found that parties are spending big on the platform but there are serious gaps in information about where that money is going. There are also questions about the way that third parties are using Facebook and the extent to which governments are giving up control to these companies to oversee the way in which money is being spent.

What do we know about spending on Facebook?

As a country renowned for its electoral regulation and oversight, the UK provides more information than most about election spending. However, there is remarkably little data about Facebook. While parties are required to declare their election spending, they are not yet required to report exactly how much of it was spent on digital advertising as a separate category. In our paper we dug around in the Electoral Commission database to try and throw further light on the way parties are using online platforms.

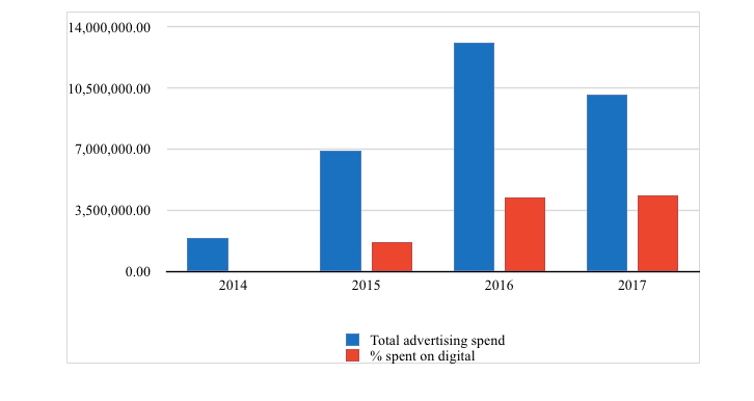

Despite the fact that political parties don’t have to provide a detailed breakdown of exactly how they spend their money, by law they are required to report spending in broad categories to the Electoral Commission. From a 2018 Electoral Commission report we know that there has been a significant rise in spending on digital advertising – even if the spending that has been reported is not the full amount. In 2014, only £30,000 (1.7% of the overall advertising budget) was spent on online advertising, yet by 2017 this figure had risen to £4.3m (42.8%).

Spending on advertising and digital advertising

Party spending returns also show that just over £3.16m was spent on Facebook advertising by all UK parties at the 2017 general election. That compares to just over £1m on Google, £54,000 on Twitter, just under £25,000 on Amazon and just £239,000 on “traditional” advertising in national and regional media outlets.

When political parties or campaigns spend money on Facebook they can target adverts or videos at specific sections of the public. This might be an ad from Labour suggesting that it’s the only party that can “stop Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party” or the Conservatives arguing that Labour “won’t deliver Brexit”. These adverts will then be set to appear primarily in certain timelines – such as those of users aged between 35 and 44 and/or living in England.

The full picture?

What this data does not reveal, however, is precisely how Facebook campaign budgets are spent. Many of us want to know, for example, if parties are paying for micro-targeting – the practice of using data to develop personalised messages for voters. But the available data does not reveal what kind of adverts parties are paying for, or how widely these are seen. It’s also hard to work out how much money is being spent on Facebook via marketing and research companies, rather than directly from a party to Facebook. This is also true for offline campaigning, suggesting this is a wider issue around advertising spending.

The data tells us, for example, that the Conservative Party paid consultants the Messina Group just over half a million pounds for market research, advertising and transport during its 2017 general election campaign. We also know that Messina spent money on Facebook. But we don’t know what proportion of the money that went to Messina was spent on Facebook. We therefore can’t tell how much money in total the Conservatives spent on the platform.

In response to pressure, Facebook has introduced some new transparency measures to help to bridge the gap. However, outside an election period, official regulation around disclosure is severely limited. We know, for example, that between October 2018 and April 2019 People’s Vote UK, the campaign to hold a second Brexit referendum, spent £433,384 advertising on Facebook. Pro-Brexit group Britain’s Future spent £422,746 and anti-Brexit group Best for Britain spent £317,463. That’s over £1.1m spent on Brexit-related advertising on Facebook. Yet we know little about who is backing these organisations, and whether they have any links to official party campaigns.

Facebook is a marketplace

There’s another important factor at play when we think about regulating Facebook spending. In the offline world, it is easy to interpret electoral spending figures because the items declared tend to have a fixed cost. If a party spends £10,000 on leaflets, it will get the same number of leaflets as any other party would.

However, £10,000 spent on Facebook adverts by two parties can result in very different campaigns. This is because as we show Facebook operates on auction principles. Adverts do not have a fixed cost but vary according to which audience an advertiser wants to reach, and the nature of the content produced (with more engaging content being cheaper).

So advertisements to a target audience in a marginal constituency will be much more expensive than a general message in a safe seat. Content that gets watched and shared by people becomes cheaper, whereas parties with less engaging material see the price increase. These principles make it hard to work out precisely what a declared spending figure bought the party in terms of content. It also creates an uneven playing field for parties, effectively pricing some out of using this tool in the way they want.

Official statistics that simply show summary spend therefore offer little insight into how Facebook is really being used by political parties.

Understanding such limitations is vital in order to think about whether and how existing reporting requirements need to change. It won’t simply be enough to apply existing spending principles to the online realm. A lot of what we do know is a result of political pressure on Facebook to increase transparency around the way political actors use the platform. However, we should all consider the extent to which these platforms should take the lead in matters which strike at the heart of the way democracy works. Or whether – to borrow a phrase – governments and regulators ought to take back control.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Katharine Dommett has received funding from the ESRC and British Academy

Sam Power has received funding from the ESRC and the British Academy.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News