Kobe Bryant's communities come together to grieve his loss and close his story

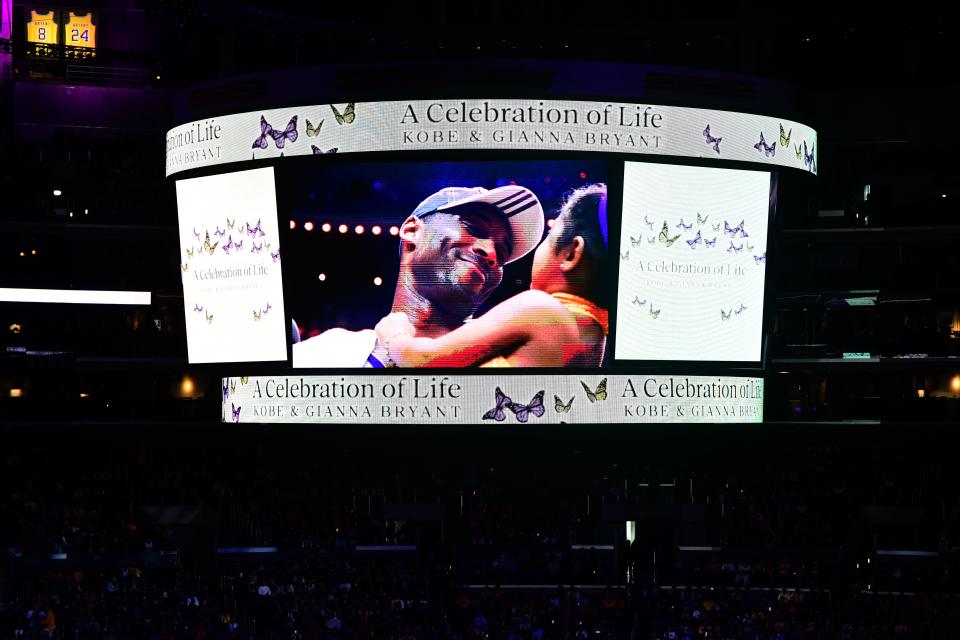

ORANGE COUNTY, Calif. — At 9:33 a.m. PT on Sunday, Jan. 26, 2020, Los Angeles Lakers general manager Rob Pelinka’s phone buzzed in church. Kobe Bryant, his best friend and former client, on his way to his daughter’s basketball game, asked if he could help his friend, Orange Coast College baseball coach John Altobelli, help secure his daughter Lexi an internship at a baseball agency. Recounting the tale to 20,000 mourners at Staples Center on Monday, Pelinka called it “a foggy, sunless morning.”

Down in Garden Grove, Santa Ana councilman Dave Penaloza is participating in the Tet Festival, a celebration of the Vietnamese New Year.

At 10 a.m., two skydivers are supposed to kick off a parade by jumping out of an airplane and landing on the route. But the clock keeps ticking, and delays turn into a cancellation. “All small aircraft have been grounded from John Wayne Airport,” Penaloza recalls the fire marshals saying. “Because of the fog and because apparently there’s this missing aircraft.”

Mildly disappointed, the parade-goers shake off the inconvenience. Floats float. Dancers dance. Toward the end, the news spreads: Kobe Bryant and his 13-year-old daughter Gianna were among nine people who perished in a helicopter crash, along with John and Keri Altobelli and their daughter Alyssa, Sarah Chester and her daughter Payton, as well assistant coach Christina Mauser and the pilot Ara Zobayan.

Penaloza immediately thinks of the missing aircraft. His colleagues on council agree to light the historic 153-foot water tower off the Interstate 5 freeway in yellow and gold. Cars congregate around it. Fans snap selfies. The city receives hundreds of “thank you” emails. Penaloza recognizes a desire for connectedness, organizing a viewing for Bryant’s memorial.

Across Los Angeles, a similar phenomenon takes hold. Artists paint murals and drivers blast music. Fans just show up at Staples Center. They know where to go. They know to bring flowers, basketballs, sneakers. They dress in Kobe apparel, a public acknowledgment of grief.

Gina Kornfeind, a bereavement counselor at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital and lifelong Angeleno, understands the patterns of grief and death so well it’s alarming. She studies what most of us are too scared to face. We run away from grief because it reminds us of our own mortality. But when it comes to mourning Bryant, few are shying away. “Having such a public display of grief in a community, it un-marginalizes regular grief,” she says. “There’s a lot of people that feel traditionally marginalized because of our society’s fear and shame of death.” Famous athletes and late night hosts have cried on primetime. Fans mirror them, wearing their pain in public. “It feels acceptable and OK to do because the public is doing it,” Kornfeind continues. “It’s like this role modeling and permission.”

The weeks since Bryant’s death have often felt like a communal funeral. He spent 25 years in the public eye. He has played the hero, the heel, the husband, the husband on-the-outs, the accusation of sexual assault, the baller, the artist, the neighbor, and finally the father who lost his daughter heading to a game, a pilgrimage familiar to countless parents and kids.

Monuments in Dubai, Toronto and New York were lit purple and yellow, standing in concert with the water tower in Orange County, where Kobe lived. The fog cleared but left the city in a haze.

Leading up to Monday’s memorial, however, Southern California struggles to find a collective mourning site. Over 88,000 requests pour in for tickets to Bryant’s memorial. Only 15,000 can be granted. Fans are urged to stay away from Staples Center. The memorial won’t be televised there. Most shops by nearby LA Live are closed. Where do you go when the place you need to go is barricaded off? Some people plan, like Penazola and his colleagues, setting up a viewing at Santa Ana City Hall. Others transgress. They’re all searching for the same thing: communion, remembrance, an ending to the story.

At Memorial Service Park, a disarmingly friendly security guard ushers me down a hill toward the gates. Media are not allowed at Bryant’s burial grounds. Fans are being urged to avoid the gravesite. Some put flowers and jerseys on the wrong gravestone, followed by visiting the wrong funeral home altogether.

I’m not interested in the burial site as much as I am in the people who are drawn to it. Abbi and Brandon, two fans wearing Lakers apparel, emerge from the hill I was sent down in a red SUV. They didn’t know about the controversy, they just felt a natural desire to pay their respects. The urge to get together and ritualize in the face of death is ancient, older than humans. Death unhinges us. This is how we screw ourselves back in.

Then there's Leo, an Orange County resident that shows up with a friend. They know they’re not supposed to be here and show up anyways. They tried and failed to get tickets to the memorial. “Now, they told us, don’t go,” says Leo, wearing a Manchester United jersey, yellow flowers resting in his hand. “If they didn’t tell [us] that, we’re gonna go Staples, be right around the vicinity, even though we don’t have tickets.”

Leo attended Bryant’s final game. He says a mural he painted of Bryant was featured on TV. A lover of street art, he has traversed Los Angeles, Orange County and San Diego to photograph Bryant murals. In pursuit of the gravesite, the duo seems peeved that security keeps following them, even as they actively seek them out. “We’re not here doing something nasty,” Leo insists.

I tell him the funeral home probably wants to protect the family’s privacy.

“But you know, superstars … you cannot tell people not to go because they are part of the public. That’s unavoidable. You don’t have a public life anymore,” Leo responds, not so much crossing the line that separates public and private grieving as considering it invisible.

Inside the beige Stucco-lined walls of Santa Ana City Hall, about 100 residents splattered in purple, gold and black shuffle through the doors of the council chambers and settle into wooden, teal-cushioned seats in the auditorium. At first, they considered setting up a Jumbotron and displaying Bryant’s memorial in the courtyard at City Hall. But they invited residents to watch inside “to be cognizant of cost and feasibility,” Penaloza puts it.

Penaloza and his colleagues wanted to mitigate the roadblocks that kept the community from connecting. People here feel like they knew Bryant. They saw him with his family. The night before he passed away, Penaloza saw his friend post an Instagram story of Bryant’s at Fashion Island. Penaloza referred to the nine passengers who perished as “Orange County fixtures.”

“A lot of Santa Ana residents attended Orange Coast College and took health and CP3 classes with Coach Altobelli,” he says. Bryant helped mentor the basketball team at Santiago High School, three miles from City Hall.

Hosting the memorial, late night host Jimmy Kimmel draws laughter when he jokes that the Lakers finally got Bill Russell, who wore a Kobe jersey to Sunday’s game between the Lakers and the Celtics, on their side. The crowd in council chambers laughs with the crowd in Staples Center. We clap when they clap. We cry when they cry. We are the crowd we’ve been searching for.

The room erupts in conversation. A 20-something man in a black sweater embroidered with the TV show “Friends” logo and a camera hanging from his neck introduces himself. Jack, whose real name isn’t Jack, is a credit analyst who called in sick to watch the memorial. We exchange pleasantries and he asks if he can sit next to me. I shuffle over, and we interrupt our chat as Vanessa, Bryant’s wife, takes the podium.

She talks about Gianna, about the idiosyncrasies as to keep her alive, the fact that Gigi was sarcastic, that she loved to bake, that her youngest sister, Capri, is a lot like her. Toward the end of Vanessa’s speech, I’m crying. Jack’s crying. He asks me if I’m OK. I lie and ask him. He notes, through tears, that he’s feeling better than he expected to.

We all came here to be alone together and here, for a brief moment, we were. Bryant was a hero to Jack. He calls him a life-changing figure. “He’s been in the public eye for so long and we’ve been through it all with him,” Jack says. It’s been like a relationship, going through the valleys and the peaks, the near break-ups and then back to the championships. When it comes to the charges made in the sexual assault case against Bryant in 2003, he says we are limited to our knowledge.

He concludes that on the whole, Bryant did more good than harm, citing his efforts to empower women. He takes a page from his hero’s book, highlighting some facts and ignoring others, crafting the best story for his reality.

We have all tried to write our own stories around Kobe’s death — maybe he spent his last seconds comforting his daughter — but only Bryant, the NBA’s best storyteller, could make sense of the tragedy that befell him. Stories, in fact, are why we’re shocked. After seeing it and hearing it for so many years, we truly believed Bryant was invincible. ESPN’s Ramona Shelburne wrote that after tearing his Achilles heel, Bryant became obsessed with the myth of Achilles, the Trojan war hero whose choice was to die young, leaving a glorious impact, or to live a long, unremarkable life. Maybe he’s Achilles. That sounds right, doesn’t it? But even the tale of Achilles has been rewritten and jostled over. Was he really an only child?

Vanessa, in tears, takes a crack. “God knew you couldn’t be without each other.” My Lyft driver says a variation of the same thing. So does Debra Jackson, mentioning that every day since the accident, the sky has been clear. “It came and went,” she says of the fog. “and maybe this is when he was supposed to go.”

According to Kornfeind, “50 percent of the population who have a loss, a traumatic loss or an untimely loss, go onto have post-traumatic growth. People probably think, ‘Oh my gosh, poor people, it’ll never be the same, their life is over.’” Nihilism becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. She gives grieving parents to a new language to understand their lives. How, for example, could Vanessa respond to the question of how many kids she has? “‘I have four kids: three are here with me, one in heaven,’” Kornfeind says. “We teach our families how to have a new narrative.”

If, as Joan Didion put it, we tell ourselves stories in order to live, we edit them to survive. Oregon star Sabrina Ionescu said she finds herself texting Kobe, hoping for a response. One morning, she prayed, looking for a sign.

The next morning, she stared at the sun — it was Lakers yellow, she insists — and saw a helicopter in the distance. Was she searching for something that isn’t there? Or maybe, is the search the entire point?

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo News

Yahoo News