Kochland review: how the Kochs bought America – and trashed it

If the unbridled consumption of fossil fuels is indeed pushing the planet faster and faster toward Armageddon, Charles Koch probably deserves as much credit as anyone for the end of the world as we know it.

Related: Dark Money review: Nazi oil, the Koch brothers and a rightwing revolution

Christopher Leonard never makes that judgement in Kochland, his massive study of one of the most destructive corporate behemoths America has ever seen. But in more than 600 pages, he provides plenty of evidence to support it.

Charles and his late brother David were second-generation extremists. Their father, Fred, was not only one of the founders of the John Birch Society, which famously accused President Eisenhower of being a “tool of the communists”. He also helped the Nazis construct their third-largest oil refinery, which produced fuel for the Luftwaffe – although you would have to read Jane Mayer’s brilliant book, Dark Money, to learn that particular detail.

In 1980, David Koch was the Libertarian candidate for vice-president. The party’s modest plans included the abolition of “Medicare, Medicaid, social security (which would be made voluntary), the Department of Transportation, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission.”

“The party,” Leonard writes, “also sought to privatize all roads and highways, to privatize all schools, to privatize all mail delivery” and, eventually, the “repeal of all taxation”.

Such political ambitions never got very far, although the family did purchase the Republican senator Bob Dole’s friendship with $245,000 in contributions and David served as vice-chairman of Dole’s 1996 presidential campaign.

David’s main contribution to the family firm was to try to launder its name, plastering it on everything from the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center to the Hall of Fossils at the National Museum of Natural History, via hundreds of millions in charitable contributions.

It was Charles who had the focus, ambition and business acumen – and it made almost everything he touched radioactive. Nothing was too trivial to feed the family’s greed, starting with the systematic theft of oil by mis-measuring amounts removed from storage tanks.

A federal investigation of this massive scheme was dropped by Timothy Leonard, a US attorney chosen by Koch ally Don Nickles, an Oklahoma senator. Here, the author rather credulously accepts Leonard’s denial of any political influence over his decision, made with his hand on “a Bible that he said belonged to his grandfather, a Presbyterian minister”.

Though the feds declined to prosecute, the Koch’s dissident brother Bill brought a civil suit based on the same set of facts. That led to Koch officials admitting they had earned roughly “$10m in profits each year by taking oil without paying for it”.

From this not-so-petty theft, the book proceeds to tales of massive pollution surrounding a Minnesota oil refinery, when retention ponds filled and the operators decided it was better to inundate the surrounding ground than send the ammonia-filled waters directly into a nearby river.

“A belief in the power of markets created a disdain for the government agencies tasked with regulating Koch,” Leonard observes. The company paid nearly $20m in civil and criminal penalties but the fines, “while historic, would not dent” profitability.

Related: Death and destruction: this is David Koch's sad legacy | Alex Kotch

The same refinery was the site of some of the Kochs’ most successful union-busting. But the macro damage has been caused by their five-decade attack on FDR’s New Deal.

In 1974, Charles Koch explained: “The campaign should have four elements: education, media outreach, litigation and political influence.”

When Congress finally began serious consideration of a carbon-control regime, the Koch brothers saw a mortal threat. Besides the thinktanks, university research institutes and industry trade associations they funded to turn out trash science debunking global warming, their spending on Washington lobbying exploded, from $2.19m in 2006 to $5.1m in 2007 and $20m in 2008.

“In 1998,” Leonard writes, “the Koch Industries PAC spent just over $800,000. In 2006 it was $2m; in 2008, $2.6m.”

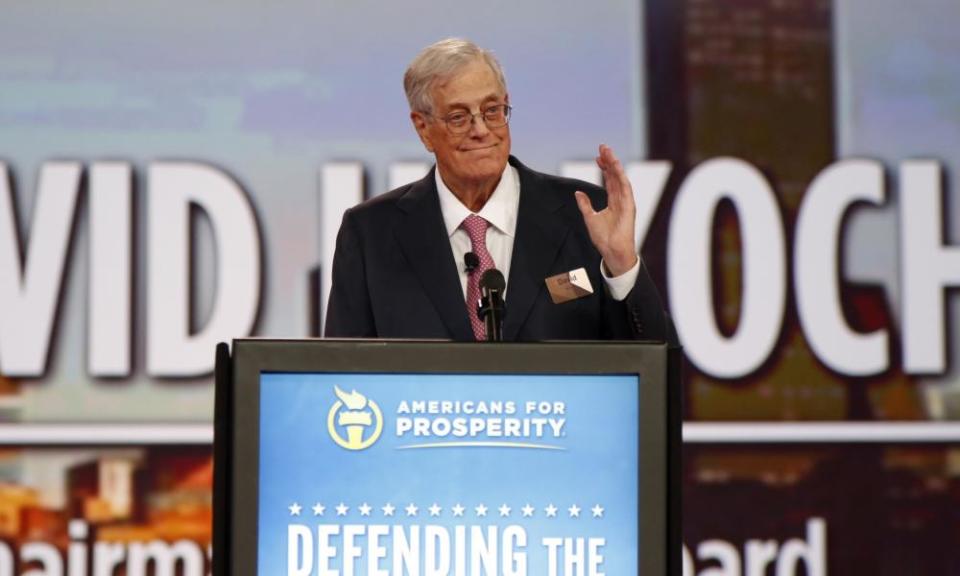

Americans for Prosperity, an advocacy group run by the Kochs, funded the Tea Party, eliminating from Congress just about every moderate Republican. In 2007 it spent $5.7m, then $10.4m in 2009 and $17.5m in 2010

That year, the Citizens United supreme court ruling removed many restrictions on corporate cash, making it possible for the Kochs and their allies to purchase the climate position of Congress. After the House passed a comprehensive carbon control measure at the beginning of the Obama administration, the Kochs made sure it died in the Senate.

Because the Kochs are nothing if not thorough, they did the same on the state level, lobbying legislatures to eliminate incentives for renewable fuels. This ensured constant growth in the huge family fortune.

Leonard writes: “During the Obama years – the years when Americans for Prosperity warned repeatedly about the threat of creeping socialism – Charles and David Koch’s fortune more than doubled once again. At the end of the Obama administration, Charles Koch was worth $42bn. Together, Charles and David were worth $84bn, a fortune larger than Bill Gates’.”

Related: The Koch brothers tried to build a plutocracy in the name of freedom | Nathan Robinson

Kochland makes it abundantly clear that everything that has been great for Koch industries has been catastrophic for America. And yet Leonard seems oddly ambivalent.

After spending hundreds of pages describing horrors inflicted on the environment and the body politic, Leonard tells us Charles Koch is finally finding “a sense of contentment” through a new book project. His close friend Leslie Rudd tells us: “I think Charles is doing just exactly what he wants to do, which is trying to do good.”

Leonard concludes that Koch will show his “market-based management” philosophy was not just a guidebook for operating companies, “but for operating entire societies. The proper shape of American society was the shape of Kochland.”

This is a very strange way to end a book about the wholesale pollution of land, air and water and the evisceration of American democracy.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News