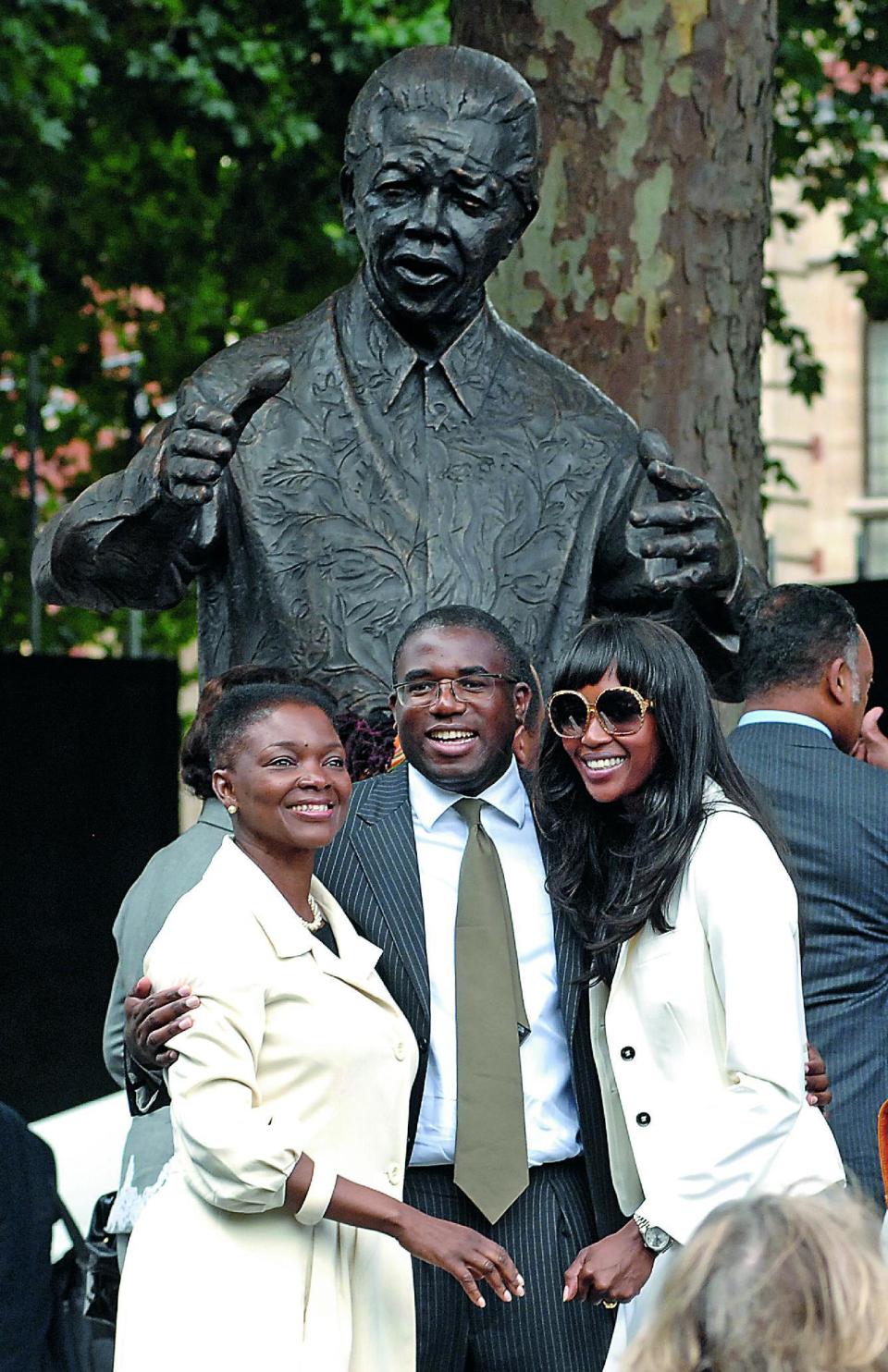

Labour MP David Lammy on Windrush, Grenfell and using Twitter to address race bias

Why does David Lammy want to be interviewed, I ask as we sit in a soulless room in Westminster over a tape recorder.

Lammy is robust, confident and laughs easily. But ask him this and he goes a little coy. ‘We are doing these [interviews] every day and we think, “Oh God, the same,” but actually some person going out to Essex is reading ES on the train and they haven’t accessed a lot of the other things I’ve done.’

Oh, Mr Lammy, an eye to expanding your reputation?

This little exchange betrays something about Lammy, 45, who has been MP for Tottenham for 18 years. Over the past 12 months it has been difficult to miss him. He has been a controversial critic of the Government on Grenfell, prominent commentator in the Windrush scandal and in the thick of the debate around gang violence, which has erupted in London. All of them play to his own background: he is the son of Caribbean immigrants and was brought up in the poor district of Tottenham. But by becoming the megaphone man on these issues Lammy is stuck in the inner city. He’d like to get out more.

‘I do find it frustrating [and] sort of weird that I’m constantly being described as “passionate” — “You spoke on this, you spoke on that,”’ he says, aware of the caricature that is developing. ‘I don’t think I should be the exception. I think this is where we are. I mean, when people burn to death in a tower and 71 people are dead, why is it so controversial for David Lammy to say that this is corporate manslaughter? When four young people are killed in the London Borough of Haringey in the first four months of the year, and we’re now at over 60 [across London] and it’s still not even the summer yet, how is that not something to get passionate about? And if it’s not, is it because they’re black?’

His constituents appreciate him. At the 2017 election, he was returned with more than 80 per cent of the vote, one of the largest majorities in the country. ‘I just know my response is what people are talking about in the barber shop, what people are talking about when they’re getting their nails done, what people are talking about on the Tube,’ he says. ‘I can’t explain what’s going on in Westminster. Westminster has disappeared up its own backside that’s called Brexit, I suspect, but I’m doing what I think I have to do.’

But all this politics of experience is not landing him a front-bench role — nor, it would seem, wider respect within his party. Just after meeting him I run into a Labour colleague who rolls his eyes at the mention of Lammy, complaining of his being a Blairite virtue-signaller.

What did he do so wrong? The son of Guyanese parents, he was raised by his mother, who worked her way up from a secretary to a manager in Haringey Council. His father, a taxidermist, walked out when he was 12. Lammy’s fine singing voice won him a scholarship to the only state-run cathedral school, The King’s School in Peterborough. He went on to SOAS University of London and then became the first black Briton to study a masters in Law at Harvard. Elected MP for Tottenham in June 2000, from 2005 to 2010, he worked as one of Blair’s ministers, first in culture, then innovation and skills under Gordon Brown. After that, however, he fell back. Neither Ed Miliband nor Jeremy Corbyn picked him out for a shadow ministerial brief. He tried to be Labour’s candidate for Mayor in 2016. The party didn’t want him, it wanted Sadiq Khan. And so his pulpit became the back benches.

He’s more prominent than many on the front bench. One of his signature subjects is gang violence in London: in Wood Green, in Ilford and in his own constituency, Tottenham. By March the capital was beating New York in the murder statistics. Donald Trump sent one of his hyperbolic tweets about there being ‘blood all over the floors of this hospital’. Lammy can talk fluently on so-called ‘county lines’ — how London gangs are franchising their drugs operations out to market towns — and about how kids are drawn into these worlds. But there is a perception that he is too quick to blame the Government, and too slow to blame the man wielding the weapon.

He talks about the victims of knife violence and immediately cites Kobi Nelson, a reformed gang member who was killed this year, and the older cases of Ben Kinsella and Godwin Lawson as examples of innocents stabbed on the street. I have to push him to admit that not all the ‘victims’ in the recent violence were just bystanders, that a number of them were allegedly part of the gang scene. ‘Yes, sorry, of course, of course,’ he concedes and moves on.

Lammy’s way of deflecting those questions is to compare what happens in Tottenham with elsewhere. He’s almost enraged at me asking if he still doesn’t support stop and search. ‘That is a very binary question,’ he says, citing the number of young men who get criminal records for cannabis possession as a result. He trots out a favourite line: ‘We also know that there are lots of middle-class people in Notting Hill snorting cocaine on a Saturday night and they, too, almost are in a decriminalised context.’

Then there is drill music, the soundtrack to much of the violence London has seen this year. Originally from South Side Chicago, the London drill crews who’ve emerged rake in millions of views and local followers. Their lyrics are loaded with threats. The hooded crews who make the videos that appear on YouTube have names such as 67 or Moscow 17, from which a reported member, Rhyhiem Barton, was gunned down this month. If Lammy is resistant on stop and search, he’s paradoxically hard line on drill music. Would he support the Government beginning to legislate to get YouTube to take these videos down? ‘Absolutely. I mean, I had a meeting with YouTube and I thought their response was pathetic.’ But is that not cultural suppression, I ask, to provoke the liberal in him? ‘Politicians have always blamed the music. So I don’t want to be guilty of that. I’ve always been clear: the central problem is not the music, but I do think that clearly we are in a frontier where there will need to be better regulation than there currently is. If we want to be urban downtown Chicago, we’re heading in the right direction.’

There’s a reason some call him ‘passionate’. It is a covert way of saying ‘not reasoned’. Take Grenfell, in which Lammy was personally invested: he knew the young Gambian-British artist, Khadija Saye, who died in the fire, and Lammy spent a lot of time on the ground there. A politician playing the game would have deferred to the Met Police for an official death toll. Not Lammy. In the aftermath he said the death toll estimate, then 79, was ‘far, far too low’. Challenged by Andrew Neil, he wouldn’t recant. The Met tally later settled at 71. And as the anniversary of Grenfell approaches, asked again, he still holds his line. ‘We need to listen to the people who lived on that housing estate and those people feel that more people died in that building than the 71 that we know about.’

On the Windrush scandal, he could again speak from experience. When the new Home Secretary, Sajid Javid, said, ‘I thought that could be my mum... my dad... my uncle... it could be me,’ it could have come more accurately from Lammy. But when I ask if identity politics, the bread and butter of his recent work, has held him back he stops and says: ‘That’s a good question.’

‘In the age of Trump and Farage and Rees-Mogg, I get defined and I’m subjected to a lot of race bias,’ he says as a half-answer. He says he didn’t enter politics with the patronage of other people, such as the Miliband brothers, Ed Balls or James Purnell, the Oxford PPE graduates who landed jobs with Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. ‘I was just David Lammy from Tottenham whose parents were David and Rose Lammy. It’s okay. I’ve learnt to speak quite well and put a suit on…’ Harvard seems to have been forgotten.

Despite him embracing the man-of-the-street identity, warrior of conscience, he has not become a member of the Corbyn inner circle. When I start talking about Momentum, I notice he won’t say the word ‘Momentum’, but talks around it. The vehicle behind Corbyn is rife in north-east London. His neighbouring MP Stella Creasy is under continual threat of deselection and Claire Kober, the former leader of Haringey Council, stood down under pressure at the last local election, replaced by a Momentum-aligned leader, Joseph Ejiofor.

Lammy spoke out against Kober in her plans for a housing regeneration scheme of 6,400 homes in Wood Green, over which she resigned, saying the council under her was ‘high-handed’ and ‘out of touch’. Is it not hipsterfication that bothers him? ‘I’m all for mixed communities,’ he says. Saying there was not enough social housing was his way of committing to neither side.

But does he fear Momentum? ‘I don’t really do tribal Labour politics. I wasn’t delivering leaflets from the age of seven. I wasn’t that engaged in student politics. I haven’t been fighting some of the battles some of my other colleagues have since they came out the womb.’ That’s a subtle dig, I think, at Creasy, who is dogged by accusations of being a bit too upper class for Labour. Not that Lammy hasn’t clinked champagne glasses himself. His wife, Nicola Green, with whom he has three children, is a distinguished portrait painter who has exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery and is currently preparing an exhibition on religious leaders.

If Lammy can’t find his base in the Labour Party, no wonder he’s looking outside, to suburban commuters or indeed to Twitter, on which he bangs out his views. He compares himself, by accident, to Churchill, when we talk. ‘If you think about the great parliamentarians, if you think of Churchill and the way he was pushing a position in the run-up to the Second World War, he had the wireless and millions of people were gathered round as he pushed that agenda. Thank God he did.’

He’s not so keen when I mention that a closer comparison in the current media game is Donald Trump, who used bombastic tweets to raise his base. ‘That goes back to your question about identity politics. Whether I like it or not, I feel that I’ve got to have something to say or I’m very quickly going to be redundant really. I can’t represent the kind of place I represent and not have something to say in the age of Trump.’ His two-minute speech on the ‘national shame’ of Windrush went viral and he’s loving the attention. ‘People can approach me in the street. Emails from Canada, Australia, Trinidad, Jamaica, Guyana. Because it’s two minutes long, I think, people are able to access it very easily. That’s the age we’re in.’

But Lammy remains caught in this trap of the sound bite over the deep politics. Is his unwillingness to lose some of his base a lack of confidence? He sticks to the areas in which he’s comfortable. I suspect he’d quite like the Home Office shadow brief, given his interest in policing and immigration, though Corbyn’s old friend Diane Abbott occupies that spot. Is it he who is holding himself back, by playing to the gallery and relishing the two-minute viral clip? Or is it us wanting to pour him into a mould?

Lammy isn’t defeated though. ‘If I get the call to do it from the front benches, then I’ll think about,’ he says. ‘But I’ve got huge job satisfaction, I really have — the job is like drinking from a hosepipe.’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News