The last-ball drama of Essex v Notts is memorable 30 years on

Everybody remembers the ending. With one ball remaining Nottinghamshire had to score three to win, and steal the Benson and Hedges Cup away from Essex. “To bowl the last ball was John Lever, 40 years old, 40 years wise,” wrote Mike Selvey in the Guardian. “Facing was Eddie Hemmings, four days older than Lever and no less wise or yeoman-hearted. It was a shoot-out of the old brigade. A game now of bluff, double bluff and raw nerve. Gooch and Lever took an eternity to set the field. Lever breathed deep and set off.”

It was 1989; Essex were the most successful side of the decade and apparently on their way to winning everything again. Three times in the 1980s they had won the County Championship, and three times the Sunday league. This year they led them both, topping the county table after 12 of 22 games with a handy 33-point lead over Worcestershire (to put that in context, none of the next four teams were more than 12 points further back), and in the Sunday Refuge Assurance League, having played 11 of their 16 games, they were four points ahead of Lancashire at the top. The Benson and Hedges Cup could have been the first of an improbable, glorious treble.

Related: When Ian Botham played king at the panto and the 1992 Cricket World Cup

They were one ball from the trophy. Just one perfect delivery. At that stage of his career Hemmings had played 13 one-day internationals and had a batting average of four. He also had a groin strain, declaring later that he might not have been able to run a sharp couple had such an effort been required. “I had a little meeting with Bruce French while they were moving the field all over the place for about five minutes,” he remembered. “I said: ‘I’d better hit it for four, hadn’t I?’ He said: ‘No choice.’ Then all of a sudden Goochie moved deep cover over to the leg side, and one of my favourite shots was to back away and hit it through the off side, so that’s what I did.”

Lever said: “If I’d just run up and bowled, I’d have been fine. But we stopped and spent five minutes changing fields around. Third man came up, then back. Fine leg came up, then back. I knew where Eddie was going to go: outside leg stump. My job was to follow him. Standing around, it was a long five minutes. I followed him, but I didn’t quite follow him enough.”

Selvey continued: “The ball was close to perfect – almost yorker length and outside leg stump. But Hemmings, reading Lever’s mind and trusting Lever’s skill, stepped inside the line and sliced the ball away with horizontal bat.” Brian Hardie, midway through his 39th year, set off in vain pursuit. “It’s a gamble,” said Gooch. “You put your fielders where you think the ball will go. There will always be gaps. John bowled it in the right place. Eddie just found one of the gaps. The whole day’s play came down to one ball – we did our best and lost.”

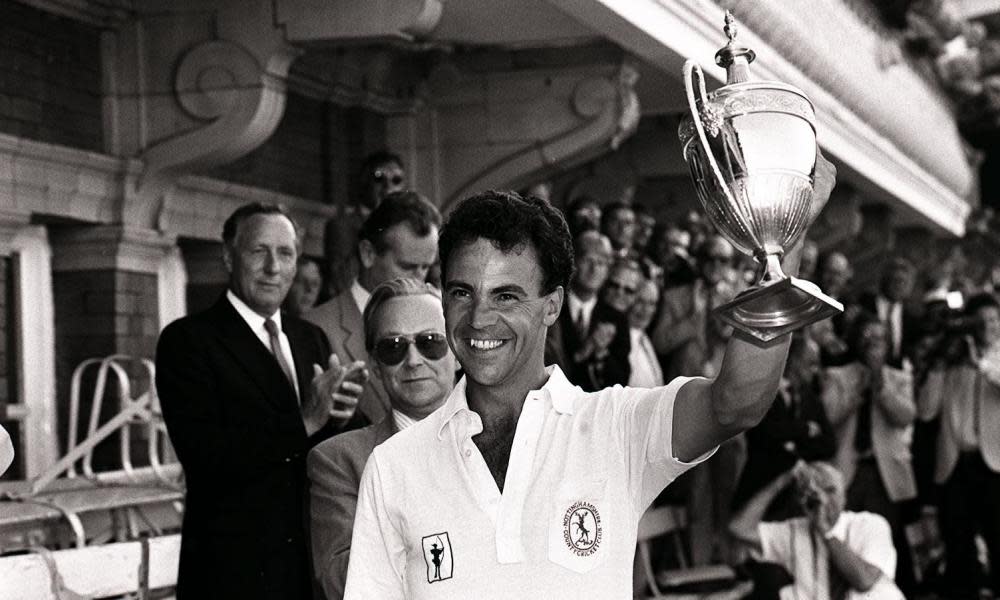

Essex had lost the first leg of the treble and went on to lose the other two as well, coming second in both domestic leagues. Hemmings seemed to forget his injury as he and French spun and whirled in celebration, slapping each other’s backs joyously with bats still clutched in their right fists. It was 30 years ago next month, and remains one of the great domestic limited‑overs matches – or at least among the greatest finales. Selvey declared it “one of the great games of one‑day cricket”, though Alan Lee in the Times sniffed that “it was, in many ways, a mundane match, remembered only for its epic climax”.

Which is perhaps a little unfair, for there was another classic moment at the other end of the game. In the third over of the match Essex were four without loss, with Hardie yet to score. Franklyn Stephenson had befuddled him with one of his slow balls, and was about to try again. “Hardie didn’t worry me as a top batter but if I’d listened to all the rhetoric about him I would probably have got a little uptight because everyone was telling me that he was Nottinghamshire’s nemesis,” Stephenson writes in his new autobiography, My Song Shall be Cricket, which will be published on the 30th anniversary of the 1989 final, 15 July. “Starting proceedings from the pavilion end, I bowled him a few deliveries which climbed nicely and left him trying to keep them down. All good, ease your way into the match, Franky.”

Stephenson remains famous for his slow ball. The previous year he had scored 1,000 first-class runs and taken 125 wickets, estimating that a third of them had come with the delivery. He passed his methods on to his flatmate Chris Cairns, who at the time of the 1989 final was a 19‑year‑old scholar at Nottinghamshire and four months away from his Test debut. Wasim Akram and Steve Waugh both developed a slow ball after watching the Barbadian. Hardie, however, had not been paying attention.

“I bowled him a slower ball and he totally missed it,” Stephenson writes. “He ducked out of the way and was very fortunate that it didn’t bowl him because he never saw the ball and it only narrowly missed his stumps. I was amazed by his reaction. He almost freaked out.

“By that stage of my career it wasn’t the greatest surprise in the world that Franklyn Stephenson could bowl a slower ball, eh? I made my mind up to give him another one, to see what his reaction would be this time. He’d been ducking and diving around, giving an impersonation of a blind man holding the bat. A couple of balls later down came another slower one and he played all around it and was bowled, gone for a painful 10-ball duck. Essex were 4-1. Despite all the advances in the modern game people still remember things like that.”

There have not been many domestic matches that have proved as dramatic or as memorable, but Stephenson and his slow ball would play a key role in one of them. Four years later, in the NatWest Trophy final, he was delivering the final over for Sussex and Warwickshire needed 15 off it. Dermot Reeve scored 13 off the first five deliveries, leaving Roger Twose, who was yet to score, to find a couple from the last. Stephenson bowled his famous slow ball, Warwickshire won, and Stephenson was forced to feel the pain endured by Lever on that memorable day in July 1989.

• This is an extract taken from the Spin, the Guardian’s weekly cricket email. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions

Yahoo News

Yahoo News