The absolute beginners' guide to Pidgin | Kobby Graham

The launch of BBC Pidgin will come as a bit of a shock to many African parents and headmasters, and will leave many others confused as to why the world’s foremost exponent of the Queen’s English, the BBC World Service, is investing in what is often called “broken English”.

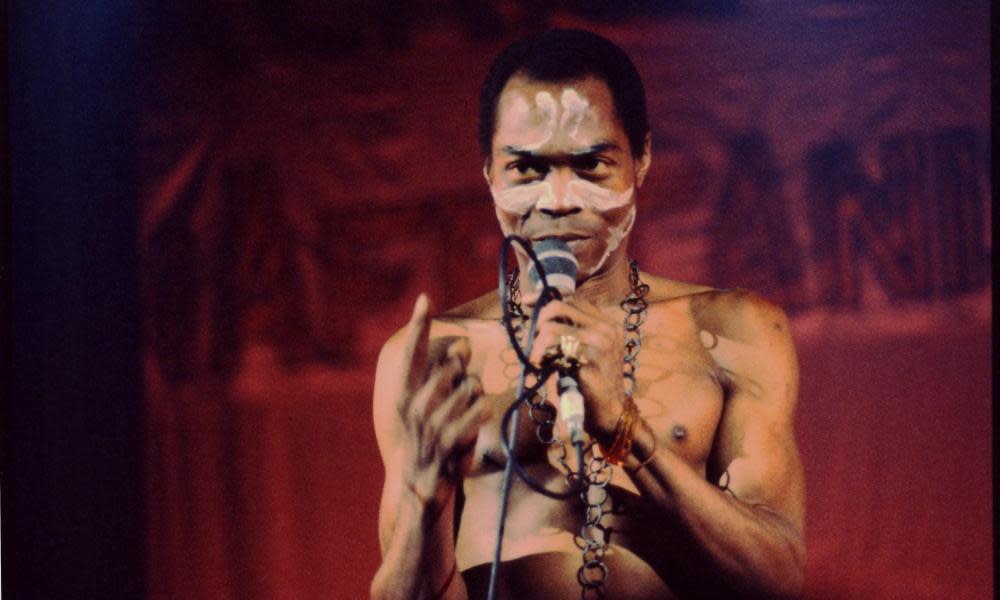

But Pidgin is so much more. It is the widely spoken (and wildly inventive) lingua franca of much of west and central Africa. Fela Kuti once sang, “I no be gentleman at all o”, using Pidgin to underline his defiance against being “civilized”. Today, the language is a cultural force, driving everything from the lyrics of Afrobeat music to movies emerging from Nigeria’s Nollywood, now the world’s second-largest film industry.

West African Pidgin began in the late 17th and 18th centuries as a simple trade language between Europeans and Africans. Combining basic nautical English vocabulary (itself derived from regional English variations) with the grammar and composition of languages of the various ethnic groups British traders encountered, it stripped things to the bare necessities: “I am going out, but I will be right back”, for example, became “I dey go come”. To date, “I dey” can mean anything from “I am here” or “I am waiting” to a statement about the victory of one’s continued existence: “I am still here”.

The education system the colonialists created used English as a tool to “civilize” Africans, suppressing local language and culture and creating a hierarchy that put those who spoke English well – and best parroted British culture – at the top. To date, English is still the language of white-collar African employment.

Changes in Pidgin, compared to a rather static English, always point to wider demographic and societal trends

Despite the best attempts of generations of educators to stop its use, speaking Pidgin – as well as English – remains the best proof that you attended the ethnic melting pots that are west African secondary schools. At the same time, changes in Pidgin, compared to a rather static English, always point to wider demographic and societal trends.

For example in my secondary school days in the late 90s, we would say “that thing be deft” to describe something as being rubbish. My younger siblings who attended the same schools a decade later would instead use, ibi yawa, which sounds suspiciously like Hausa. Nigerians have almost always been the largest non-Ghanaian population in Ghana and we share many Pidgin words, but my siblings’ time at school also coincided with Nigeria’s cultural dominance across the continent through its music and film industries.

Pidgin is defined by its practicality. Fluency will reduce how much you have to pay for cab fares or market tomatoes. And as you needn’t be literate to speak it, across anglophone west and central Africa – made up of many diverse ethnicities and languages – there are more people fluent in shared Pidgin languages than in English. Marketers and the media are cottoning on. Advertising in Pidgin – once unthinkable – is now commonplace. Wazobia FM has been broadcasting entirely in Pidgin to Nigeria’s 75 million Pidgin-speakers for almost a decade, a fact certainly not lost on the BBC World Service in its biggest African market.

William Tyndale once had to apologetically explain why he felt the need to print a dictionary in a language as backward as English. Today, mainstream English dictionaries have new words added every year – such as selfie, bling and bootylicious – to explain new ideas and phenomena. There is some irony here: Africans sold into slavery were not allowed to speak their languages, forcing them to use Pidgin to communicate and making them good at shaping new words. Years later, their descendants are some of the most regular contributors of new words and terms to English.

It is the absence of rules that makes Pidgin incredibly adaptive. In Ghana, new words emerge on an almost monthly basis: dumsor (off and on) came out of nowhere to beautifully and simply describe our persistent electricity problems; a meme about hustling gave us kpakpakpa. In comparison, Ghana has only ever contributed Harmattan and a few diseases (like kwashiorkor) to the English dictionary. One day when language experts examine this period, the English language won’t tell them very much about Africans. Pidgin is where our inventiveness will be on full display.

• Kobby Ankomah-Graham is an Accra-based lecturer and writer

Yahoo News

Yahoo News