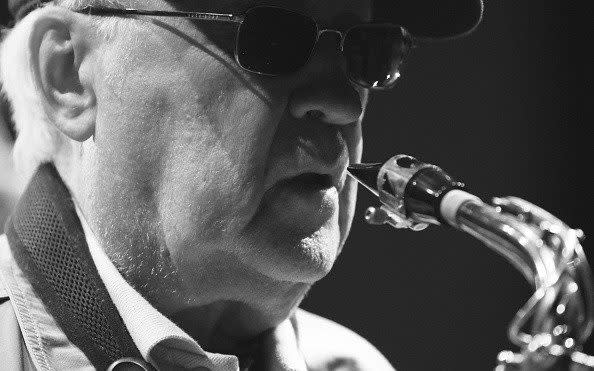

Lee Konitz, saxophonist who was at the forefront of jazz’s ‘Cool School’ – obituary

Lee Konitz, who has died aged 92, was an important figure in the development of jazz during the post-war period. He remained an active and innovative musician into advanced old age.

As a young man, Konitz was the most prominent among the very few alto saxophonists unaffected by the powerful influence of Charlie Parker. His calm, almost vibrato-free tone and undemonstrative style were the antithesis of Parker’s passionate intensity. Along with other musicians, such as Stan Getz and Gerry Mulligan, Konitz came to represent a new tendency in jazz, known as the “Cool School”. Although, like Getz, he broadened his approach in later life, the “cool” label never quite wore off.

Leon “Lee” Konitz was born in Chicago on October 13 1927, to parents of Austrian and Russian Jewish descent. Inspired by hearing Benny Goodman on the radio, he took up the clarinet at age 11, later switching to saxophone. He became a professional musician at 18, playing with the orchestras of Teddy Powell and Jerry Wald, among others. In 1948 he was a member of Claude Thornhill’s band, which contained several future leaders of the cool school, including Mulligan and the arranger Gil Evans.

In 1946, Konitz met Lennie Tristano, the blind pianist-composer who was to influence his future musical life. Tristano had evolved an original approach to jazz improvisation, and a teaching method based on ear training, both of which impressed him: “Lennie was a musician-philosopher. He got through to me. Suddenly I was taking music seriously.”

He studied with Tristano and often played in bands under his leadership. One of their early recordings together, Intuition (1949), is the earliest known example in jazz of completely free, unprepared group improvisation.

The search for an effective orchestral style to complement the playing of cool jazz soloists led to the formation in 1948 of a nine-piece band under the leadership of Miles Davis. Later dubbed the “Birth of the Cool” band, this was a racially mixed group, but Konitz found himself the target of complaints by disgruntled black saxophonists. Davis retorted that Konitz was there for his playing, not his colour, and “I wouldn’t care if he was green with red breath”.

Cool jazz took root very early in Europe, especially in Sweden. In 1951, Konitz was one of the first American jazz musicians invited to play there. He visited again in 1953, as a member of Stan Kenton’s orchestra, this time recording with a mixed band of American and Swedish musicians. His influence on the style of local saxophonists is quite noticeable on the resultant records.

After leaving Kenton, Konitz led a series of bands, often composed of fellow Tristano disciples. Prominent among these were the tenor saxophonist Warne Marsh and two British musicians, pianist Ronnie Ball and bassist Peter Ind. In 1956 he toured in Europe with the Swedish baritone saxophonist, Lars Gullin, and the Austrian tenor saxophonist, Hans Koller.

But public tastes in jazz tend to shift rapidly from one extreme to another, and at the end of the 1950s cool jazz was eclipsed by the more vigorous “hard bop” style. Despite a critically admired album, Motion, in 1961, Konitz virtually retired from performing for a few years, preferring to concentrate on teaching.

His method for teaching jazz improvisation, partly based on that of Tristano, was a version of “variations on a theme”, to which he gave the name “Ten Steps”. The student began by adding small embellishments to a given melody, replacing it by gradual stages with his own invention.

The tunes used as the basis for this were almost always the classic American songs of Gershwin, Porter, Kern et al, employed by generations of jazz musicians. Apart from occasional forays into avant-garde territory, Konitz himself remained faithful to this repertoire throughout his own playing career.

On his return to performing in 1965, he found his most enthusiastic audiences in Europe. He spent long periods on this side of the Atlantic and, through his work with musicians such as Albert Mangelsdorff, Martial Solal, Stan Tracey and Wolfgang Dauner, was influential in the development of a distinctively European approach to jazz.

Konitz developed a great fondness for the duet form, relishing the intimate, one-to-one exchange of musical ideas that it offered. He began in 1967 with an album, The Lee Konitz Duets, featuring a variety of partners, including trombonist Marshall Brown, violinist Ray Nance and guitarist Jim Hall. There were further duet recordings in later years, notably with the pianists Michel Petrucciani (1982) and Harold Danko (1984).

In 1992, Konitz was awarded the Danish Jazzpar Prize, the most prestigious of all jazz prizes and the only one with real money attached – equivalent to about $30,000. (It is currently in abeyance for want of a sponsor.)

Konitz was a musician whose dedication was so intense that it left little time for much else. His discography is enormously long, amounting to around 120 items under his own name and a further 50 as a sideman. The frequency of record releases actually increased slightly following the Jazzpar award. His final album appeared in 2018.

Lee Konitz was married three times. He is survived by two sons and three daughters.

Lee Konitz, born October 13 1927, died April 15 2020

Yahoo News

Yahoo News