Lib Dems are bouncing back, but revival is not guaranteed

As so many times in recent history, the Lib Dems’ fortunes have been largely linked to events beyond their control.

Labour’s equivocation on Brexit at the local and European elections, disarray in the Conservative party, whose next leader is likely to set the UK on a path to no deal, and the embarrassing collapse of Change UK meant the seeds of revival were being sown in fertile ground.

It did not always look so promising. Even at the beginning of this year, the outgoing leader, Vince Cable, was still deeply frustrated that the party could not seem to shift its poll position from single digits. His party members threw out proposals to let non-MPs stand as leader, a desperate attempt to attract a celebrity figurehead.

When Labour MPs such as Chuka Umunna left their party, it was briefed that they could never join the Lib Dems because they were a “toxic brand”.

Yet just a few months on, the party has doubled its poll showing, won back hundreds of council seats, beaten Labour at the European elections and Umunna is now sporting a yellow rosette.

Cable’s tenure as leader was not flashy, but he has done groundwork behind the scenes that will give the next leader a good base, including new donors, better infrastructure and revived local activists.

At the local and European elections, the advantage that the established parties had was enormous. Thousands of Lib Dem door-knockers had voter data on a mobile phone app that dated back decades. Change UK ran their European campaign almost entirely on social media and poorly attended rallies.

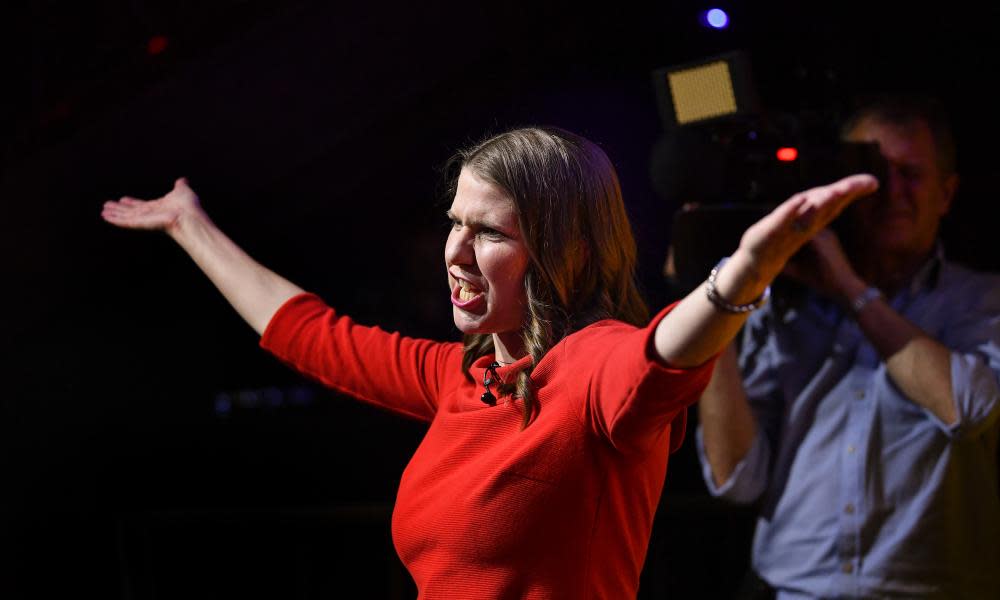

Related: Jo Swinson: youthful veteran long seen as natural heir to Vince Cable

Suddenly, a legacy brand with a still-loyal army of supporters prepared to go out in the rain seemed like an underrated asset.

The next six months will be key to a Lib Dem revival. Jo Swinson should get an early boost to her leadership – barring a major upset, the party should take the seat of Brecon and Radnorshire.

More defections also seem likely from former members of Change UK, including Sarah Wollaston and Heidi Allen, who could join at the party’s conference in September.

However, in the medium term, Swinson’s fortunes depend almost entirely on events outside her control, the most immediate being whether Boris Johnson takes the UK out of the EU on 31 October.

Once Brexit has happened, “stop Brexit” ceases to function as a USP for the Lib Dems and the new leader will have a difficult choice about whether to campaign solely on how bad Brexit may have been for the country – particularly a chaotic no deal – or whether to launch straight into a campaign to rejoin the EU.

The other key factor will be Labour’s transition to a pro-referendum party and whether that coaxes back disillusioned voters. The party still faces questions from those who are passionately pro-EU about what position it would adopt in a snap general election.

Swinson can also talk passionately about the identity issues that matter to many young Labour voters – her victory speech rallied against violence against LGBT couples and Islamophobia and antisemitism in both main parties.

All those factors would suggest the Lib Dems might find it far easier to capitalise in a snap general election, rather than one held in 2022, when a “re-join the EU” campaign might look far-fetched, with Labour then well placed to talk anew about inequality and division and a Johnson government possibly boosted by the swift decline of the Brexit party, even if a betrayal narrative still exists among the hardcore.

An emergency election this autumn would give the Lib Dems a good opportunity to mop up swathes of disillusioned remainers. A recent poll for Politico suggests Johnson repels possible Lib Dem voters, particularly in London, Scotland and the north-west, giving the likely next prime minister practically zero hope of building an electoral coalition that also includes progressives.

A snap election could yet pose a dilemma, especially if the Lib Dems make gains and end up holding the balance of power. Swinson, though more open to pacts than her rival Ed Davey, has pledged never to prop up a Corbyn government in coalition, though if a snap election came and a confidence-and-supply agreement with Labour was the route to a new referendum, it would be hard to see the Lib Dems turning down that opportunity.

Yet many of the Lib Dems’ new members and voters are those who have left Labour, either as members or voters, and might be angered by any deal-making with Corbyn. Or they may be fickle and return to voting for the reds once they feel Labour has truly become the main “remain party”.

The Liberal Democrats are right to be wary of doing deals. From Clegg-mania to the massacre in 2015 where Swinson herself lost her seat, they know better than most that a hyped revival can easily be followed by a calamitous fall.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News