How the life and death of Annie Leifs shows how women have disappeared from history

Reykjavik. It’s the middle of the 20th century. A woman with dark eyes stands outside a small stone house in the old town. The woman inside is afraid she will cast a spell of misfortune over her family. In the house lives Iceland’s most famous composer with his third wife and young son. Outside stands the woman who sacrificed everything so Iceland’s greatest musician could come to be. The woman who has disappeared from history.

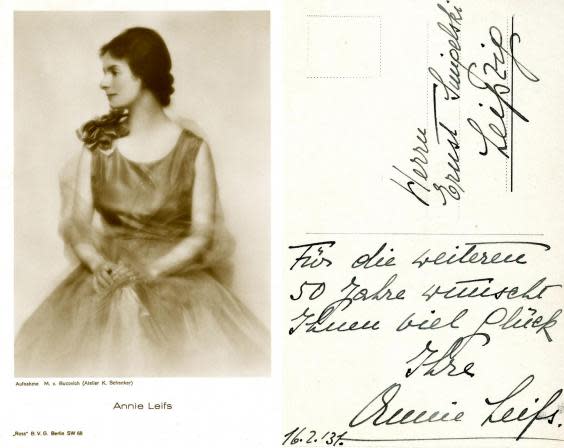

In March 1918, a young German woman named Annie Riethof plucked up the courage to speak to the boy she had a crush on for the first time, and became forever tangled up in Iceland’s history.

The man in question was 18-year-old Jon Thorleifsson, or Jón Leifs as he chose to call himself. Annie and Jón met while studying music at the Leipzig Conservatory of Music. But the paths that led them there couldn’t have been less alike.

Annie was born into a wealthy family in Teplitz in 1897 (now Teplice in the Czech Republic). Her father, Edwin, was a factory owner with a love of painting and her mother, Gabriele, was a promising pianist. Annie and her older sister Marie grew up (in the city where Ludwig van Beethoven began writing his Symphony No 7) surrounded by music and art.

In contrast, Jón grew up in Reykjavík, which at the turn of the century was a small town with only 6,000 inhabitants, no art scene and little opportunity to engage in cultural activities. Jón was one of only a handful of children to learn to play the piano. By 17, he had managed to convince his parents to let him drop out of college and sail to Germany to study music. “Victory,” Jón wrote in his diary.

Jón and Annie’s romance soon turned into a serious relationship. When Annie graduated she chose to remain in Leipzig to stay close to Jón.

As Jón’s graduation date drew nearer, his health started to deteriorate and he spent long stretches of time in hospital. In his book Jón Leifs and the Musical Invention of Iceland, the musicologist Arni Heimir Ingolfsson argues that Jón’s condition may have been psychosomatic, caused by his deepfelt doubts about his musical abilities. He had wanted to become a pianist and a conductor, but believed he would never become good enough.

Annie was many things to Jón throughout their life together. During the first years of their relationship, she played the muse: it was to Annie that Jón dedicated his first complete composition. When Jón got sick, Annie and her mother dedicated themselves to taking care of him.

There was, however, one member of the Riethof family who did not fall for the charms of the young Icelander.

When Annie and Jón started talking about marriage, Edwin opposed it. Jón wrote to him: “For the past two or three years I’ve been in complete agreement with you; marriage should not only be built on ‘chemistry and love’. But when a woman with an independent mind crashes into the world of my creativity I’d never forgive myself if I didn’t take advantage of her services in my human endeavour at artistic feats – even if I don’t know if I can ever repay her.”

But this did not sway Edwin, and Annie and Jón got married against the wishes of their parents two years after they first met.

A musician without an instrument

Although Annie’s family was wealthy, what awaited the newlyweds was grinding poverty. Annie and Jón tried to find work as musicians – Annie as a piano teacher, Jón as a conductor and composer – but it was far from lucrative and they struggled to make ends meet.

Annie’s career soon took a back seat. Her time was increasingly spent on tending to Jón’s ambition, helping him find inspiration, taking care of him while he was sick and promoting his music. It was Annie who came up with the idea that Jón use Icelandic folk songs as an inspiration for his compositions, which would become his trademark.

Historians have a duty to not overlook the footprints of those who tread lightly, humbly, through life

In 1926 Jón decided to travel with a symphony orchestra to Iceland, where the sound of such an orchestra had never been heard before. Annie helped Jón organise the trip, and put her grand piano up as collateral for the tour. She didn’t get it back until five years later.

Despite Annie’s focus on Jón and his needs, in 1928 she performed in one of Europe’s greatest concert halls, the Salle Pleyel in Paris, to critical acclaim from the French press.

Annie and Jón had two daughters, Snot and Lif (which means “life” in Icelandic). Despite the family often living in acute poverty, Annie always encouraged her husband to ignore their parents’ pleas for him to give up on his dream. In 1927 Jón wrote to his parents: “My first duty is to not give up on my vocation. I’m convinced that my work is more important than the work of most men.”

But Annie’s support was never reciprocated. Nor was her loyalty. Jón made no secret of his love for other women. In a letter to his wife, Jón told her about his latest crush. “I thought you’d thank me for telling you the truth right away – but you just make things difficult for me!”

Soon, however, their marital problems were overshadowed by a looming threat.

‘A new start is never easy’

In 1933 Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. Annie was Jewish.

The fate of her parents was tragic. “Dad was released from suffering on 12 February,” Annie wrote to her sister in a telegram in 1942. Edwin had been unwell for quite some time. In June of the same year Gabriele was arrested by Nazi forces and moved to Theresienstadt concentration camp. On 22 October, one month before her 71st birthday, she was shipped to the Treblinka extermination camp, where she died.

When it came to the politics of the time, Annie and Jón were naive. They thought that politics didn’t concern them. “Political movements and power struggles have nothing to do with art,” Annie declared many years later. She had refused to leave Germany, but after witnessing one family member after another being taken away to Nazi concentration camps, she couldn’t ignore the situation any longer. On 27 February 1944 Annie, Jón, Snot and Lif escaped to Sweden.

A new start is never easy; those who head fearlessly towards a goal will reach it

Annie Leifs

It was there that Jón fell in love with the woman who ran the guesthouse in which they were staying, and asked Annie for a divorce. Annie fought it hard, even when Jón left the family and moved to Iceland, but in the end she was forced to grant it. Her personal nightmare, however, was just beginning.

On 12 July 1947, the phone rang. It was Charles Barkel, a Swedish violinist. Lif, Annie’s youngest daughter, spent her summers with him in Hamburgsund, a small seaside town on the west coast of Sweden, learning the violin. Lif started each day with a swim in the ocean. That day, she hadn’t returned.

Annie took the train to Hamburgsund. A search party scoured the beaches, and boats, trawlers and planes were used to look for Lif in the sea. The search was largely managed by Annie. Nine days after Lif’s disappearance, when everyone except Annie had given up hope that she would be found, her body was recovered.

How Lif died would haunt Annie and Jón for the rest of their lives. Despite their relentless search for answers, they never found out whether it was an accident, or if Lif had taken her own life.

She was buried in Reykjavik, and shortly after, Annie and Snót moved to Iceland.

Once again, Annie was forced to start over. In a notebook where she chronicled Jón’s life from 1916-1937, an inscription at the front reads: “A new start is never easy; those who head fearlessly towards a goal will reach it.”

Annie sold a collection of instruments and some jewellery and established a memorial fund in remembrance of Lif, hoping that one day it would finance the construction of a Catholic monastery in Iceland. She travelled far and wide to gather support for her cause. Pope Pius XII even granted her an audience. On one of her trips, the ring and little finger of her right hand were badly damaged, which resulted in Annie not being able to play the piano as well as she used to. She was devastated.

Annie and Snót lived in a small basement flat in the old town of Reykjavik. It was difficult for Annie, who had spent her whole life around music and culture, to get used to the simple life of a small town.

She supported herself and her daughter by teaching the piano. But soon another tragedy struck. Snót, now a young woman, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Caring for Snót became Annie’s life.

Annie had a few benefactors in Reykjavik, people who recommended her teaching services to others and invited her and Snót into their home. They lived in poverty, but she was a proud woman and made homemade gifts such as drawings or German delicacies for the families that showed them kindness. (However, German cooking was not always to their liking: it’s said the children ran and hid every time they saw Annie approach with a fresh batch of sauerkraut or a plate of fried mushrooms.)

Annie often took Snót to visit Jón and his third wife, Thorbjorg Leifs, but always waited for her daughter outside the house.

Many of Annie’s contemporaries found her slightly odd. They remember her walking slowly along the streets of Reykjavík wearing dark clothes and, on Sundays, a strange hat. Sometimes she was by herself; sometimes Snót was with her, always a few paces behind her mother.

Annie Leifs died in Reykjavik on 3 November 1970. She was 73 years old. She was buried next to Lif.

The big ‘why’

The story of Annie Leifs is the story of many different things. It’s the story of a Jewish woman trying to survive in Nazi Germany; it’s the story of what it was like to be a woman at a time when they were considered mere supporting actors in their husband’s lives; it’s the story of an immigrant starting over on a cold island far away from home; it’s the story of isolation, loss and alienation; it’s the story of hope, determination and female resilience. But it’s also a story of why. Buried in Annie’s story is the answer to the question: why have all the women disappeared from history?

At first glance, it might seem like it’s the historians who are to blame; that the lack of women in history books is down to lack of interest; that historians simply need to shine a spotlight on them and they will emerge from the shadows in droves. Annie’s story, however, shows that the problem lies far deeper.

It isn’t just the gatekeeper who decides what’s written about in history books. One of the challenges historians face is the availability of source material. When it comes to primary sources – official documents, news articles, diaries and letters – it’s often hard to find anything that shines a light on what women were doing and thinking in the past. There are, of course, many reasons for this. But one of the main ones – and one of the most overlooked – is the attitude of the research subjects themselves.

Slight footprints

All his life Jón Leifs believed he deserved to be famous: “I must admit, I have craved fame like many men of my age,” he wrote to a friend in 1930. Neither Jón’s persona nor his music were particularly popular with his contemporaries. But that didn’t diminish his belief that through his music he would become immortal. “I have no doubt that my work will become classics, even if it won’t be until after my death.”

Looking at the source material, it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that Jón laid traps for historians. In a preface to a diary he started keeping when he was 16 years old he wrote: “The things I’ll be writing down here are for no man to see. These words are written by me, for me alone … After my days however, there may be those who will peek into this sanctity.”

After his death he left behind a mountain of personal documents he meticulously collected and preserved throughout his life. He saved every letter he got and kept a copy every letter he sent; he asked his parents to keep the letters he sent them; he went to great lengths to recover a chest filled with letters and documents that had been left behind in Germany when the family escaped during the Second World War. Jón Leifs secured his place on the pages of history by leaving behind a carefully curated breadcrumb trail for historians.

With Annie, however, the exact opposite is true. Neither Jón nor Annie seemed to think it necessary to preserve her story. The handful of letters written by Annie that can be found in the archives of Iceland’s National Library are all about Jón and her attempts to promote his work in Germany. In his biography of Jón Leifs, the Swedish music journalist Carl-Gunnar Ahlen writes about a scrapbook that belonged to Annie and notes: “How sad it is to see the state of the clippings of the reviews Annie received after her concert [in Magdeburt in 1923]. They have been cut up and only the sections about Jón’s compositions have been kept.”

Those who have studied the life and work of Jón Leifs, or those who knew him, all agree that he did not walk his path alone; that he would never have achieved success without help. They all say that behind the man was a woman. That woman was Annie Leifs.

Annie does appear in the two excellent biographies that have been written about Jón. There she’s cast as the supportive wife of the greatest composer Iceland has ever seen. But her life story has yet to be told on its own.

When history is drafted by the subjects themselves, sometimes the narration is characterised by blind ambition (as in the case of Jón Leifs), and sometimes quiet humility (as in the case of Annie Leifs). It’s not the fault of historians that so often it falls to egotists to determine what becomes history.

However, historians have a duty to not overlook the footprints of those who tread lightly, humbly, through life. In viewing their stories, they might discover something new, something that got lost in the sea of information left behind by those who tried to force themselves onto the pages of history.

Where are all the women? They’re there. We simply need to listen harder to hear their voices.

Sif Sigmarsdóttir is a London-based writer and journalist originally from Iceland. Her next book, published by Hodder in June, is a feminist Nordic noir thriller for young adults called ‘The Sharp Edge of a Snowflake’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News