London museum guide: The eight most mysterious objects

Inside London’s museums, you’ll find millions of objects from around the world – and that means millions of stories too.

With histories dating back hundreds and even thousands of years, the tales of how these artefacts came to be in our city are bound to have a few twists and turns along the way.

From ancient codes to a possible murder, these are the most mysterious objects you can find in London museums.

The Lewis Chessmen, British Museum

One day in 1831, this chess set turned up on a sand dune on the Isle of Lewis. To this day, no one is entirely sure how it got there. Thought to have been made in Norway nearly 1000 years ago, it is possible that the remarkably characterful Lewis Chessmen are the only surviving complete Medieval chess set in the world. To boot, there are also varying stories on how they were rediscovered - including that they were found by a cow.

The Cursed Amethyst, Natural History Museum

This jewel is a little less desirable than it first appears. The amethyst, which is said to have been looted from an Indian temple, was donated to the Natural History Museum by the daughter of Edward Heron-Allen. Allen claimed in a letter that it was cursed, and that its string of previous owners had befallen awful fates, including one who had killed himself while it was in his possession.

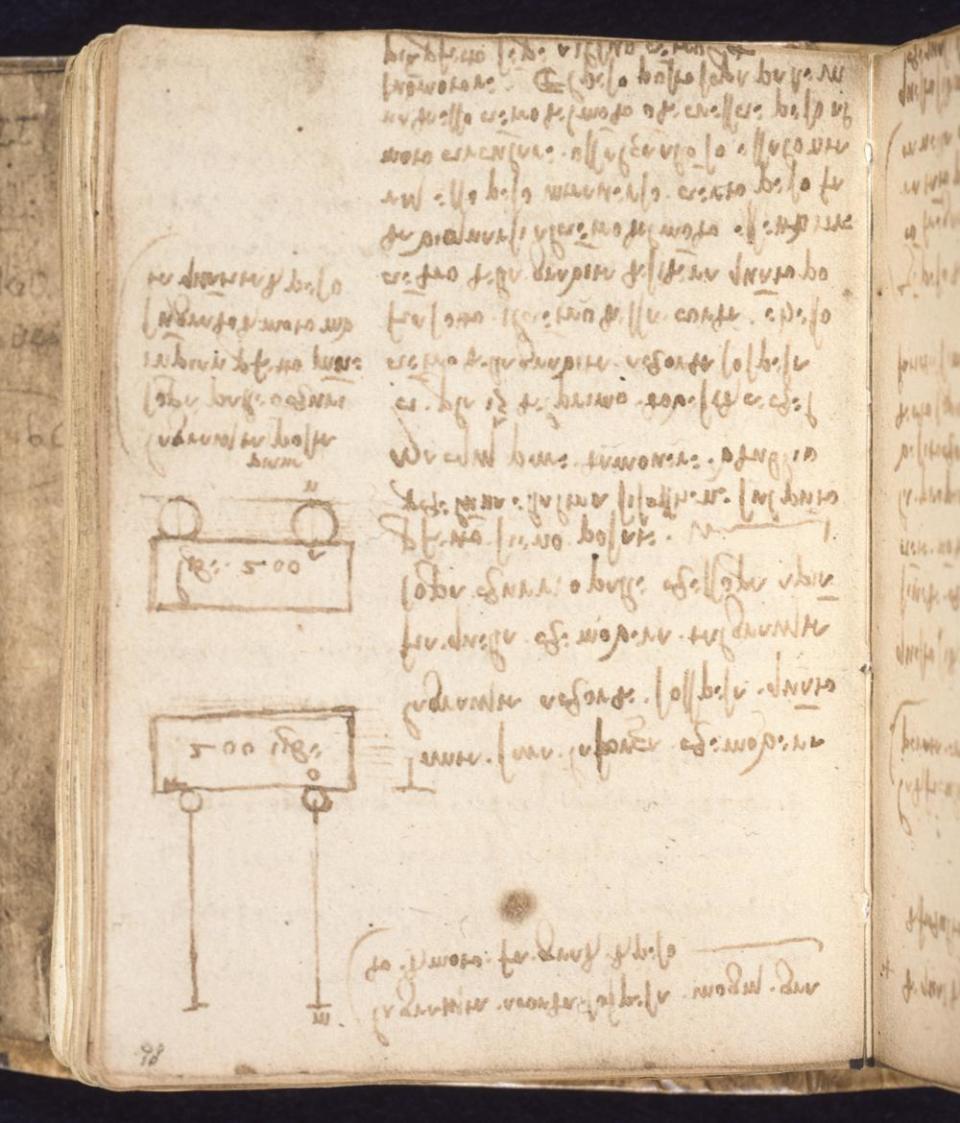

Leonardo’s notes, V&A

From designing helicopters to drawing dead bodies, Leonardo da Vinci did a lot of things differently to most 16th century folk. This included his own writing, as Leonardo took to producing his notes in such a way that they could only be read when held up to a mirror. With him being a secretive sort of guy, no one is really sure why. Theories range from a desire to hide his discoveries from his enemies, to a method of committing facts to memory, or even just trying not to smudge ink on the paper.

Merman, Horniman Museum

Forget long red hair and shell bras, this is a real mermaid – well, sort of. This guy was first shown in the UK in 1842, displayed as the “FeeJee Mummy”, an example of the Japanese tradition of mummifying real “mermen”. The Horniman Merman is quite clearly not half human, but it took scientists some extensive tests to work out what it was. It is, in fact, a man-made concoction of a fish, bits of a chicken and some pretty nifty papier mache.

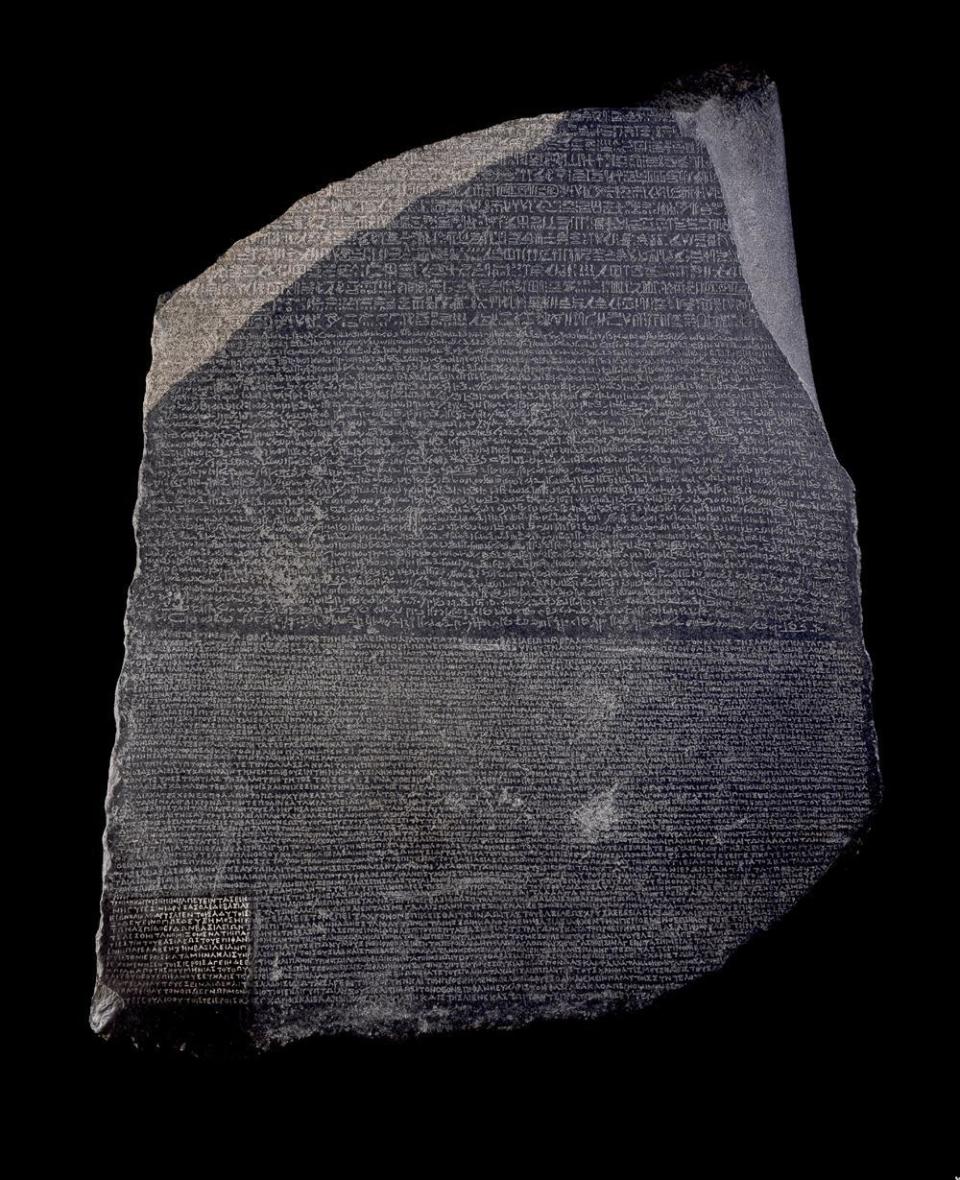

The Rosetta Stone, British Museum

Before this Ancient Egyptian stone was discovered in 1799, the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphics had been a mystery for over 1000 years. The Rosetta Stone was engraved with the same text written in sanskrit, ancient Greek and Egyptian hieroglyphics, which gave linguists the key to cracking the code. It still, however took them decades to do it.

Gebelein Man ('Ginger'), British Museum

This famous member of a group of naturally preserved mummies has been in the collection of the British Museum since 1900. And yet, it only became apparent in 2012 that Ginger – so nicknamed because of a tuft of his astonishingly well-preserved hair – may well have been the victim of a murder. Scans showed that Ginger had been stabbed in the back with a blade, quite probably by surprise.

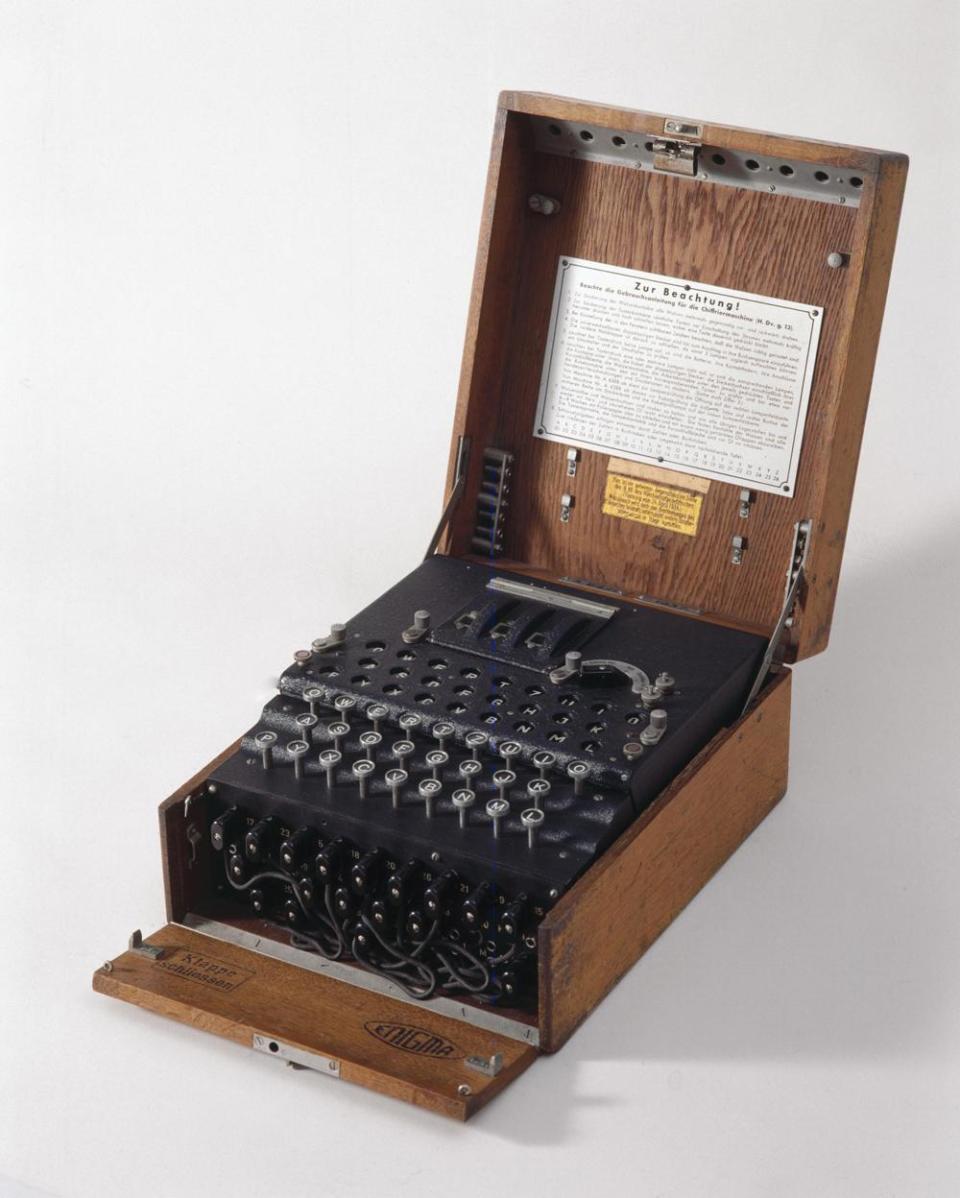

Enigma Machine, Science Museum

Long before your Whatsapps got encrypted, it was all about having one of these. The Enigma machine was most famously used by the Nazi regime to code messages so that they would remain top secret, even if intercepted. It took years for Allied mathematicians to break through the mysterious code, finally cracking it at the famous Bletchley Park base in Buckinghamshire.

Human skull cup, Natural History Museum

Not to put you off your summer staycation to Somerset, but 14,700 years ago the county appears to have been home to a group of cannibals. At Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, human remains have been found that showed evidence of defleshing and eating – including this skull carefully shaped into a drinking cup. Although scientists are not entirely sure how this, err, situation came about, it is likely to be part of a spiritual ritual.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News