London’s Roundhouse to train 15,000 young people in creative industries

A famous London music venue is opening its doors to 15,000 young people, the majority from disadvantaged backgrounds, each year to learn skills, build confidence and make connections to equip them to work in the UK’s creative industries.

The Roundhouse, which hosted Pink Floyd, The Who, Jimi Hendrix, the Sex Pistols, Fleetwood Mac, David Bowie, Elton John, the Rolling Stones, Patti Smith and Blondie in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, will open its state-of-the-art centre next month.

Roundhouse Works will be the “largest creative centre for young people in Europe” and a boost to a sector demoralised by more than a decade of underfunding, said Marcus Davey, the chief executive and artistic director of the Roundhouse.

The creative sector is rebounding strongly since the Covid pandemic, and in 2021 contributed £109bn to the UK economy. But there is a significant shortage of workers in industries including broadcasting and technology.

Barriers facing young people interested in joining the sector include insecure work, unpaid internships and inaccessible networking opportunities, said Davey. Sixty per cent of the young people joining Roundhouse Works will be from areas of multiple deprivation.

The £8m cost of creating Roundhouse Works has been raised from philanthropists, foundations and corporate donations. “We’ve had nothing from the government or the Arts Council,” said Davey.

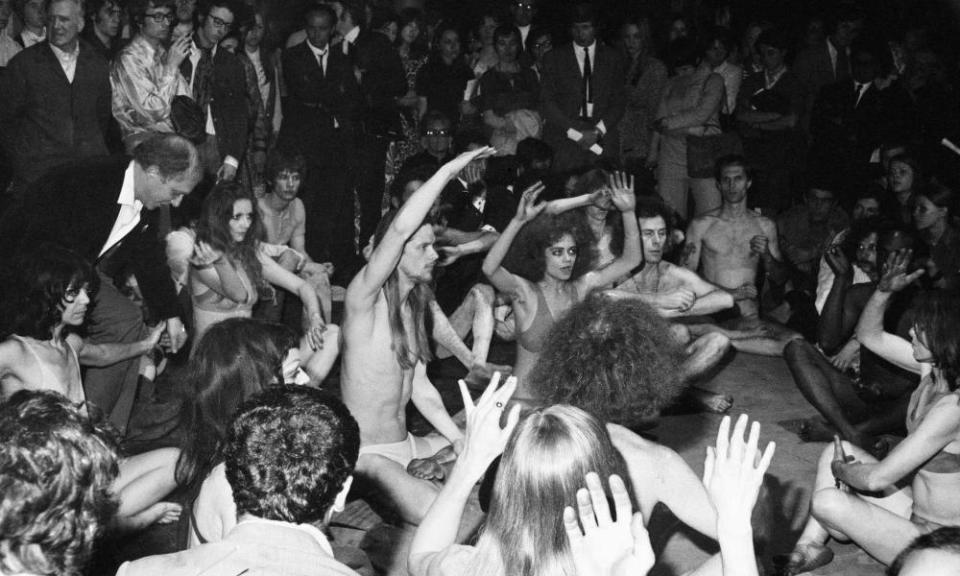

Related: Theatre in the Roundhouse: Berkoff, Warhol and an age of experimentation – in pictures

“I do think public money should be put into this because it’s about investing in the future of young people, investing in growth for our society, investing in diversity within the creative industries. And if there is a project more worthy of public money, I don’t see it.

“Money has moved out of London and there were no pots of money available to us from the Arts Council or any government department.”

Six months ago, Arts Council England announced it was diverting much of its funding outside London at the behest of the government as part of its levelling up strategy.

“Yet we’re talking about growth, about giving young people the skills and experience to have a really good job in a booming sector. And particularly for young people from diverse backgrounds. That is levelling up,” said Davey.

Government ministers had talked down the arts for the past 13 years, he said. “Arts in schools is in crisis, we’re not training music or drama teachers, the arts sector is hard to measure because of the hundreds of thousands of freelancers, and attacks on the arts feed into the culture wars.”

The new sustainable building on the Roundhouse site houses a large music studio, a triple-height studio for circus and performance, and a dedicated podcast studio as well as multi-use spaces.

Roundhouse Works will offer various membership options, giving access to work and studio space, talks, skills workshops and networking events. Help with childcare and travel costs will be available.

The venture will double the number of young people given assistance by the Roundhouse since it reopened in 2006. Among those who have benefited are the actor Daniel Kaluuya, musician Little Simz and comedy writer Jack Rooke.

The Roundhouse was built in the 1840s to store and maintain goods engines near London’s first rail terminal at Euston. In 1960, it became Centre 42, an arts and culture hub launched by the playwright Arnold Wesker – opening with an all-night rave to launch the radical underground newspaper the International Times, at which a little-known band called Pink Floyd played.

In the 1970s and early 80s, the Roundhouse featured experimental theatre, rock gigs, rock musicals and punk bands. But funding issues led to its closure in 1983. The building was unused and virtually derelict for 13 years.

It reopened as a performing arts venue in 1996, before closing again in 2004 for a two-year redevelopment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News