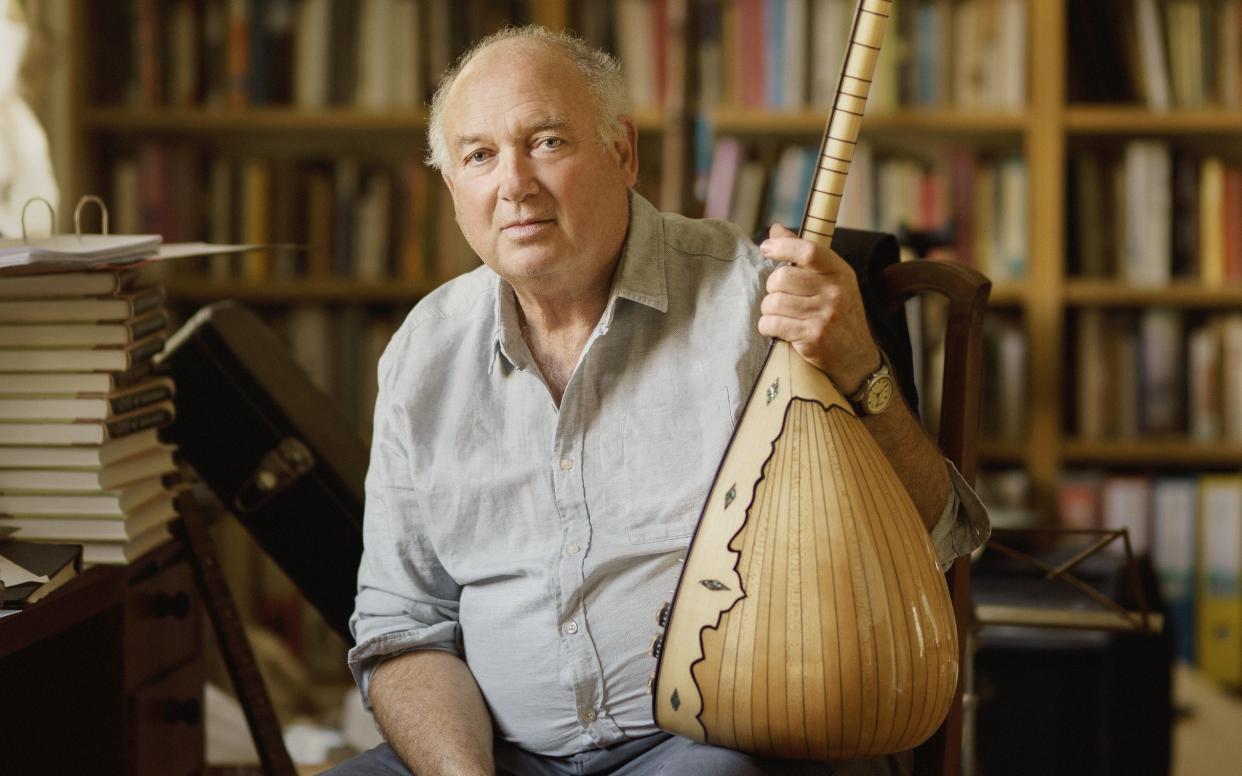

Louis de Bernières: 'Salman Rushdie was extremely unpleasant... Sometimes he’s charming, sometimes he’s really not'

Twenty five years after Captain Corelli's Mandolin was written, novelist Louis de Bernières opens up love, religion and the downsides of fame in the Telegraph's new podcast, My Life in Books

Louis de Bernières was raised an Anglo-Catholic. When he was 18 he rode on a train through Colombia and met a young woman called Maria. ‘She was chatting me up, and was wearing these fashionable platform heels.’ He frowns, recalling how she offered him a beer. He accepted, she went off to fetch it, and as she crossed from one carriage to the next, she lost her footing and slipped off the train. ‘She fell between the carriages and was ripped to shreds down one side. We were hundreds of miles from a hospital and we had to carry her back on the train. It took her about three hours to die.

'I just thought, “There’s no order, there’s no moral order.” No god that I worshipped would allow this to happen.’ He pauses. ‘The only thing I could do was try and write it up as a poem, but it was dreadful, a really, really bad poem.’

De Bernières is a rare novelist who writes best when he is very happy. Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, the fourth of his 10 novels and easily his most successful – it has sold three million copies – was written during a four-year period of utter happiness. He has never replicated its success, nor that level of bliss. But 45 years after losing his faith, he has revisited the subject in his new novel, So Much Life Left Over, about a family in the interwar years.

In it, a couple has a stillborn child and while Rosie, the wife, turns to religion as a refuge, her husband Daniel dismisses it. Eventually they separate. De Bernières seems to side with Daniel. ‘I think I am more sympathetic towards him,’ he concedes. And how does he feel now about what happened that night on the train? ‘It was more of a philosophical revelation than anything else,’ he says. ‘An almost reverse conversion.’

De Bernières lives and writes and plays the mandolin in a big white Georgian rectory in Norfolk, which he bought at the turn of the millennium, after becoming a millionaire thanks to Corelli. He separated from his long-term girlfriend Cathy Gill in 2009 and now it’s just him, Monty the dog, his two cats, and sometimes his two children, who divide their time between their parents.

Outside there is an immaculate Morris Minor – he’s had it since he was 20 – and someone has left a guitar lying on the ground. Inside, beneath the high ceilings, fleur-de-lis motifs and enormous bay windows flooding the sitting room with light, are stacks of books, CDs, golf clubs, music stands, empty cereal boxes and some pictures ‘by a Greek girl called Natalia’, and piles and piles of musical instruments, some hung on the yellow walls. There is an oud (similar to a lute), a Turkish saz (another string instrument), a homemade harp, an electric piano and stacks of mandolins. ‘I’ve no idea how many, if you know how many mandolins you’ve got, you haven’t got enough.’

De Bernières, who is 63, sits upright in a red armchair holding a mug of coffee, wearing sandals, brown shorts and a white T-shirt. His daughter Sophie, who is 10 and on her school holidays, lies on the sofa playing games on an iPad. His 13-year-old son, Robin, is upstairs. ‘He’s vegging in front of a screen.’ It is two o’clock in the afternoon and the house is very still.

So this house, I ask de Bernières, is the spoils of his success? ‘I was actually very sensible. My editor was surprised I didn’t invest in a Lamborghini and move somewhere posh, but that wouldn’t have been in character. I loved my Morris Minor. And I saved up and bought this house with no mortgage, and not having a mortgage is a blessing from heaven.’

He used to live in a little flat above a junk shop in south-west London and worked variously as a landscape gardener, a car mechanic and a teacher; but then Corelli was published in 1994. It spent 240 weeks in UK bestseller lists. Hugh Grant read it in Notting Hill. Jeremy Paxman called it ‘absolutely brilliant’. AS Byatt compared de Bernières to Dickens. Granta picked him out as one of our 20 best young British novelists, alongside Kazuo Ishiguro,and Will Self. And suddenly he became a household name and was invited to parties. In 2001, Penélope Cruz and Nicolas Cage starred in a movie of the book. De Bernières went to Kefalonia and hung out on set.

But these days he sees few people from his old circle, besides Esther Freud, who has a house nearby. ‘I’m stuffed being in Norfolk,’ he laughs quietly. ‘I like Sebastian [Faulks] a lot and I think he likes me, but I hardly ever see him. He doesn’t leave London much… I do still have friends from the best young British list in the ’90s but we’re not a clique in the way that Rushdie, Martin Amis and Julian Barnes’ generation were.’

Anyway, Rushdie, he continues, was ‘extremely unpleasant’ to him. They bumped into one another at a party. ‘He congratulated me on a novel he’d just read and I said, “Oh, I’m trying to do something much more serious now, much more difficult,” and he just looked down at me and said, “That’s your problem.” Sometimes he’s charming and sometimes he’s really not.’

Success can turn some people into difficult beasts – has he encountered many people like that? He pauses for a long time. ‘Well I hope that hasn’t happened to me. I’m lucky in having two cats who don’t give a damn who I am and two children who don’t either. But I think with some people obviously it does go to their head. They become narcissistic and irritable, and develop an intellectual contempt for other people, even when they don’t know them. The assumption is that the other person isn’t as brilliant or interesting so why bother with them, and I do think people get like that.’

Born in 1954, de Bernières’ parents had both served in the Second World War and their own parents had been through the First World War, ‘so it was a double dose of war anecdotes’ at the dinner table. They lived in Surrey on a main road and the family cats often escaped and got run over, but other than that his memories are of an idyllic early childhood. He was close to his younger sister and often took his hamster Harry to school in his pocket. At 12, when he decided to become a writer, his parents encouraged him. ‘The nice thing in my family was that it was perfectly normal to want to be a writer. It wasn’t considered daft or irrelevant.’

But then he was sent to a preparatory school in Kent called Grenham House. It was, he says, a horrendous place, and has since closed down. ‘It was a hellhole. One of the masters was a paedophile who would have his hands slipping up your shorts, and the other was a sadist, who had been tortured by the Germans. He had terrible weals across his back where he’d been whipped and he took it out on us. He was a fantastically accurate and savage beater; he could put a row with six stripes, one above the other, on your naked backside.’

The actor David Suchet also attended Grenham House in the early 1950s. On Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs he recounted similarly brutal memories, saying he was beaten for minor offences, ‘even for having Mars bars in our locker that our mum would bring’.

It is only in retrospect that de Bernières realises what a profound effect it had on him, particularly having to turn his feelings on and off, and leading an almost dual emotional life. ‘On the first day of school, you’d have to switch off emotionally. You had to be cold and unfeeling, and anaesthetise yourself. Then the first day back in the school holidays you were sat on your mother’s lap being cuddled and you had to try and switch over to being a little boy again… In some ways it spoilt my relationship with my mother.’

Their relationship remained difficult, albeit affectionate, right up to her death. He says he blamed her for his Grenham House years. Meanwhile his mother was bitter that he hadn’t given her grandchildren earlier. (He was in his 50s when Robin and Sophie were born.) ‘She said, “They won’t remember me.”’ And yet he cared deeply what she thought. Despite building a career on books largely about love and romance he always struggled with writing sex scenes, knowing she would see them. He continues to avoid them. ‘I’m still worried about what she might think of me, looking down.’

De Bernières has been described as an astute observer of the human heart. Corelli, an epic wartime love story, is one of the most popular readings at civil wedding ceremonies. The novel he’s proudest of, Birds Without Wings, is a love story set during the waning years of the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, So Much Life Left Over explores all kinds of love: a man who is in love with his brother’s wife; a mother who turns her son against his father, and a father and daughter who are fiercely close.

De Bernières was in a relationship with Gill for 11 years and when they split, a bitter custody battle over their two children followed. ‘Maybe I was naive but it had never occurred to me that I wouldn’t be equal. I work at home, I have done at least my half of the child rearing,’ he says.

At the time, de Bernières talked about having suicidal thoughts and said he had been left in a state of ‘emotional desolation’. He was angered to receive a solicitor’s letter that said he could have the children on alternate weekends from Saturday mornings until Sunday at 4pm. ‘I was absolutely outraged... But in the end we sorted it all out in two sessions of mediation and now we have them equally and everything’s fine.’

He later became a campaigner for rights of fathers and was made patron of the charity Families Need Fathers. ‘Things are changing, but it’s happening terribly slowly,’ he says now. ‘And to be perfectly frank, one of the troubles is that there are so many bad fathers who don’t give a damn and it spoils it for the rest of us.’

He drops other ex-girlfriends and breakups into our conversation often, and muses that his difficulty finding a partner might be partly due to his success. ‘It has a big downside. Suddenly a woman will fancy you who wouldn’t have done if you were still a schoolteacher. The whole situation is a bit false.’ He seems to hanker after earlier, simpler days.

At 15, de Bernières settled on a career in the Army. ‘I wanted to be a national hero,’ he says. By 18, however, he just wanted to be a hippie – play guitar, grow his hair long and lie around in sleeping bags – but having won an Army scholarship that had covered his school fees, he was obliged to enter Sandhurst and was put on a fast-track officer-training course. Then he began to suspect he was actually a pacifist and, months later, just after the conflict in Northern Ireland escalated, he quit. Nevertheless, many of his books focus on the armed forces.

In So Much Life Left Over, Daniel is a celebrated RAF flying ace struggling to adjust after the war. ‘Well it left me with huge respect for people who actually can hack it in the military. It takes fantastic physical endurance, equal to an Olympic athlete. I just couldn’t keep up with that.’

After Sandhurst, de Bernières moved to Colombia for a year, where he worked part-time as a cowboy and learnt the art of throwing a lasso. ‘That year out was the most important thing I’ve ever done in my life,’ he says. ‘It can be tremendously fun, going to live in a developing country, because if you’ve got any money at all you can get up to disgraceful things.’ Like what? ‘I mean, every girl wants to know you.’

By the time he published his first novel, The War of Don Emmanuel’s Nether Parts, in 1990, he had earned a degree in philosophy from Manchester University, and along with various ‘bum jobs’, had trained as a teacher. But by the time Corelli was published four years later, he had quit teaching too, and was writing full-time, ‘diddling’ on the mandolin and playing golf two or three times a week. ‘And I had a really sweet girlfriend and the perfect cat so I think it all came out in this novel... I feel that it’s got a luminous quality to it and the reason for that quite simply is that I wrote it during the longest period of happiness in my life... I had about four years of perfect happiness, which doesn’t often happen to anyone.’

But at some point, years later, a loneliness set in. ‘I think it came from increasingly understanding that I wasn’t really like other people and wasn’t going to find anyone who was like me.’ He compares the predicament to that of ‘great’ musicians. ‘You have a certain solitude thrust upon you by there not being many people like you.’

These days he spends a lot of time sitting alone in his red armchair, not writing, not even listening to music. ‘If you looked at me you’d think I was asleep, but I’m actually doing something, which is probably lucid dreaming. I’m letting images and sounds and smells sort of come to me. It’s a state of semi-consciousness, almost like a form of self-hypnotism. When I wake up and stop being groggy, I just go off and get it all down on paper.’

That’s not to say he isn’t busy. He has recently been reciting his poetry and performed his music at the Margate Bookie festival, and just after we meet he begins publicity for So Much Life Left Over, plus he is working on a new novel that follows on from it. Then there is the book of poetry, published next month; a short story collection, out next year; he has a vague idea for a Lord of the Flies-style novel about the brutality of going back to nature; and there is a stage play of Corelli in the works, which will tour the UK next year to mark the book’s 25th anniversary.

He thinks that he’ll throw a party now that the book’s sales have hit three million with ‘red wine, dancing girls and kebabs’. But he is reluctant to dwell on that sort of thing. ‘Also I’m slightly suspicious of my own success. I think it is to be judged by posterity. There were a number of people who were fantastically famous and celebrated in their own lifetimes and are completely forgotten now, and that inspires you to modesty.’

Listen to the full interview with Louis de Bernières on the Telegraph’s new Life in Books podcast, which launches on Thursday 18 October. Also featuring interviews with Jojo Moyes, Ruth Jones, Marian Keyes and Sebastian Faulks

Yahoo News

Yahoo News