‘Lyon's a great, weird city’: Bill Buford's five years in the heart of France's food culture

There is a chapter in Bill Buford’s book Dirt – his hugely entertaining account of a five-year journey into the earthy, primal food culture of Lyon – in which he persuades local farmers that he should help in the killing of a pig. The blood from the animal will be used to make the pungent Lyonnaise speciality, boudin noir.

As with much of his book, Buford might have been careful what he wished for. The slaughter is a secretive and deeply traditional ritual. It becomes Buford’s job to stir the blood as it flows from the cut throat of the animal into a bucket, to prevent it from coagulating. Then, by mouth, he is required to blow up the casually sluiced intestines of the pig, ready to be filled by the blood and a mix of herbs and onions for the sausage. The chapter, which is not for the faint-hearted, gives an idea of the lengths to which the author went to get fully under the skin of his adoptive French city.

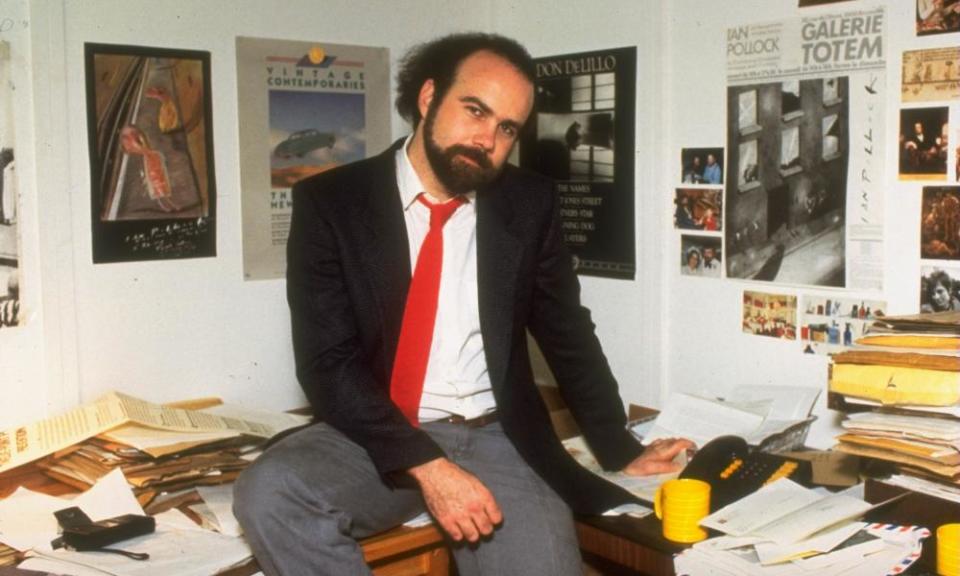

Buford, former fiction editor of the New Yorker, has form in this regard. His previous book, Heat, was a comparable quest into the soul of Italian cooking that began in the restaurant kitchen of Babbo in New York and ended with an apprenticeship to pasta-makers and butchers in the hill villages of Tuscany. Before that, when he lived in England and edited the literary magazine Granta, there was an account of football hooliganism, Among the Thugs, in which Buford became an insider in a “firm” during the running Saturday afternoon battles of the 1980s. In all three, Buford practises a kind of total immersion journalism, in which he is determined to become accepted in the tribe he describes. The pig killing – as well as stints in a Lyonnaise bakery and as a line cook at the city’s most storied kitchen – all become part of that initiation.

Of course, no proper quest is without an unattainable goal. Dirt grew out of the belief, which Buford formed when working on his Italian book, that French cooking, as we understand it, was originally an Italian import. Life got in the way of his immediate plans to test that grand theory: he and his wife Jessica Green, a former editor, now a wine teacher, had twin sons, Frederick and George. The ambition to write about France nagged away though. From a friend’s farm in Maine, where the family have been staying this summer, Buford recalls how, as the plan formed, he and Green looked at an aerial map of Lyon for a while, wondering where they and the boys might live, and then back at each other. “It really, really doesn’t look much fun,” they thought.

Buford and Green did not help themselves. Having quit their jobs they arrived, after a delay, in the depth of winter. Their apartment had no heating. In what he describes as the nadir of his marriage, Buford, who was due to bring the three-year-old twins out after Green had gone ahead to secure the draughty apartment, somehow missed the flight, and struggled to get another. “Then we all got sick and for ages I couldn’t get a restaurant to take me on.”

When I got there, I found that if French cooking had died they hadn’t told any of the participants

Slowly, with a mixture of stubbornness and charm, Buford inveigled his way into the heart of his adoptive home. (Many years ago, at Granta, I worked for him and learned to count the ways, with writers and with colleagues, he would never, ever take no for an answer: all of those tricks, and some new ones, were employed with the chefs and farmers of Lyon.)

His first success was to get a stint working alongside “Bob” (real name Yves), the city’s most beloved baker. Having learned and earned his daily bread, he then talked his way into a spot at the elite cookery school of Paul Bocuse, and from there he graduated to a terrifying and humiliating spell as a line cook at a revived city institution, La Mère Brazier, where the soul of Lyonnaise cooking had been created by Eugenie Brazier, the first female chef to gain three Michelin stars.

At the beginning, in 2008, the idea – 54-year-old American, without a word of the native language, wants to be accepted as a proper French chef – seemed preposterous. Was he confident it would succeed?

“Not entirely,” Buford says. “The thing that I was most doubtful about was learning my skills well enough that I could acquit myself as a French cook. That just seemed a long, long way away.”

If that effort was a serious – though often comical – grind, then the writing of the book has been a comparable one. Buford, an intriguing mix of high and low impulses and a world-class procrastinator, makes nothing easy. It has taken seven years to get the book done – at one point he tweeted out a picture of a stacked manuscript half as tall as he was. Perhaps as a result of that process there is a slight elegiac tone to it, as if it marks the end of something – not just the greatest adventure in the life of Buford and his family, but also a way of French life?

“In an early draft of the book I wrote all about the death of French cooking,” he says. “All the French restaurants were closing in New York and the last thing you would do is cook French. But when I got there, if French cooking had died they hadn’t told any of the participants. And now, in New York, there is a real revival of French places.”

Buford has, over the years, in his literary taste and in his writing, been drawn to the most alpha of males – he was a linebacker in American college football, and approaches some subjects as if at the line of scrimmage. In the current book there are several larger-than-life characters, but at the centre of the layers of the onion of Lyon cooking is Paul Bocuse, “Monsieur Lyon”, who is credited as the prime mover of nouvelle cuisine. Bocuse died in 2018, aged 91, having held three Michelin stars for a record 55 years.

“Almost everything that was written about Bocuse when he died was wrong,” suggests Buford. “He wasn’t a particularly innovative cook. What he represents is a connection back to the 19th century and what Lyonnaise cooking is. Perfect local ingredients and really quite rustic cooking. These great big meals at lunchtime with lots and lots of beaujolais, after which people would either go to sleep or, more alarmingly, get into their cars and drive south to the coast.”

There was also, inevitably, a cock-of-the-walk aspect to the legend: “He was always getting in trouble. With his mistresses and a Harley Davidson and a ridiculous Jeep.”

It seems to me that Buford is a little more circumspect about such excesses of testosterone in this book – or perhaps that is a result of his belief that “anarchy in France is much more within the rules”. Looming large over his book about Italy was the character of Mario Batali, the New York Italian TV chef, to whom Buford was an apprentice. Batali has, in recent years, been the subject of a series of allegations of bullying and sexual misconduct. One case, in which he pleaded not guilty to indecent assault and battery, is still going through the courts. Some of the more grotesque behaviour that characterised his kitchen in Heat now strikes a disturbing note.

Leaving aside the most serious allegations against the disgraced chef, which shocked him, Buford insists that he did speak up against the sexualised and coercive behaviour he witnessed in the kitchen, by “writing it all down”. “Mario was, at the time, someone you would have described as deeply, deeply politically incorrect,” he says, “but that is now a phrase so ancient as to have no meaning.”

In France, Buford also discovered what sounds like bullying in the kitchen, which was focused on his colleague Hortense, who worked with him at La Mère Brazier, largely from a couple of colleagues in particular. She subsequently quit her vocation. “The way Hortense was treated was powerfully wrong,” Buford says, “and this was the worst possible theatre for it – in a kitchen made famous by a legendary woman chef.” As an “embedded” journalist, he suggests, exposure has to wait. “At the time, I thought this is seriously explosive stuff. By the time I have written the book that explosion has already gone off many times.”

Does he think things have changed for good in those male-dominated kitchens after #MeToo?

“I think good kitchens are still very tough,” he says. “But I think that behaviour in relation to women is such a red flag now that I would be surprised if anyone could get away with it. They would be called out. And I think that will prove hugely positive – there are all these brilliant women chefs coming through.”

Having been enthralled as a writer by the kind of extremes of male behaviour that tip over that edge, Buford seems to have grown beyond that impulse. Fatherhood has changed him. Reading the book, you root for Jessica and Frederick and George as they try to settle in this alien place while Dad goes off to feed his obsessions with the boulanger at dawn. By the end, after five years, the boys could read and write in French but not in English.

Apart from this year, the family still go back most summers to revisit their favourite people and places. “It is a great, weird city,” says Buford. “We all love it.”

Buford is 66 now, and I’d guess in some ways more content than ever. As a younger man he seemed concerned to make sense of his relationship with his father, who had worked in the aerospace industry in California before abandoning the family in search of the 1960s. For a long time Buford spoke of writing a cathartic book about him, but he seems less interested in that now. In the course of our conversation, though, he does mention that the first time he ever visited France, aged 23, was to see his old man. “My father fell in love with the idea of France and he had left one of his wives to marry a Frenchwoman and lived on the Ile Saint-Louis for a while.”

He had been reminded of that “very crazy weekend” one time in Lyon. “We had just killed the pig, and we had gone to do the first tasting of the pork, which is this very important moment there. We went for a walk afterwards for a picnic in a wheat field and I’ve got Frederick on my shoulders, and Jessica is carrying George and it is a beautiful day. By then I was starting to master the language. I was working in a French kitchen. The boys were settled in the lycée.” In that moment, Buford thought briefly of his father – and whatever, on the Ile Saint-Louis, he might have been trying to get out of France as the American abroad. And he thought: “I’m at a spot my father never reached. The great gift of Lyon was really being open to this place we didn’t know was there.”

Buford has brought some of that insider’s understanding back to New York with him. He is writing a sporadic column on French cooking for the New Yorker. He’s had enough of total immersion, he thinks; he is happy to reflect on what he has learned.

Having experienced some years of Buford’s chaotic relationship with deadlines, I wonder if that wisdom now extends to timekeeping. Is dinner ever on time?

“Well,” says Buford. “I think I can do things in an hour but then there is like a lot of prep and a sauce and then I think I’ll do five different vegetables. Last night we ate at 9.30, the night before at 10.45,” he says. “Sometimes they all just go to bed and I’m still at the stove.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News