How we made the Big Issue magazine

John Bird, founder and editor-in-chief

It was 1967 and I was 21, sleeping rough and hiding from the police in Edinburgh. One night I came across a big-nosed Scotsman called Gordon Roddick. We exchanged insults and became great friends. He met a young woman called Anita and I didn’t see them again for about 20 years, by which time they had started the Body Shop.

In 1990, Gordon was in New York and this guy the size of a wardrobe tried to sell him a copy of a paper called Street News. They got talking and the man explained: “I buy the paper for 50 cents and I sell it for $1. It’s there to help the homeless.” Gordon thought this was brilliant. At that time, London and a number of other UK cities had thousands of homeless people. So he got money from the Body Shop Foundation to do a feasibility study about starting a British street paper.

The next year, I was having dinner with Gordon and Anita, having moved into printing and publishing, and he asked me: “Why don’t you do the paper?” I said: “No fucking way am I working with a load of white, middle-class liberals and all their do-gooding bollocks.” I wasn’t a very nice person at the time. But I said I’d do the study, for £200 a day. Gordon said £100. I talked to a lot of homeless people and they told me that anything would be better than begging. Gordon gave me the money to start the Big Issue.

It was Mickey Mouse stuff, total chaos. We made a loss and Gordon was about to pull the plug

I put together a really shambolic team. The guy who did the investigative journalism had only just left school. I got my brother to do distribution because he had a garage and a van. My assistant was a brilliant guitar-player who had never run a magazine. It was Mickey Mouse stuff, total chaos. We made a loss for months and Gordon was about to pull the plug, but we turned it around.

You could cut the commitment in the editorial office with a knife. The sense of comradeship was incredible – we knew that what we were doing mattered. Nobody wanted to go home and when we did, we’d go via the pub and get pissed together. We had a party in the office once and I took my shirt off and set my chest hair alight. You could still smell it about a week later.

There were 500 homeless organisations in London alone in 1991, giving out everything from sandwiches to condoms. But the one thing they didn’t give homeless people was a means of making their own money. What we said was: “If you’re going to help, you have to involve the homeless in their own redemption.” And that’s how the Big Issue transformed the homeless sector in this country.

Peter Bird, national distribution director

I had a cleaning business in central London. I would be out early in the morning every day and I’d see many homeless people. In Waterloo, all the arches that are now posh bars and restaurants were derelict. There’d be groups living in them, around big bonfires. It was like Mad Max.

One day, my brother John told me there was potential for a homeless magazine. I was earning good money at the time but I was bored, so I offered a hand. I remember when the first load of magazines were due to be delivered to my garage – a bloody great articulated lorry turned up my road. The neighbours had to move their cars.

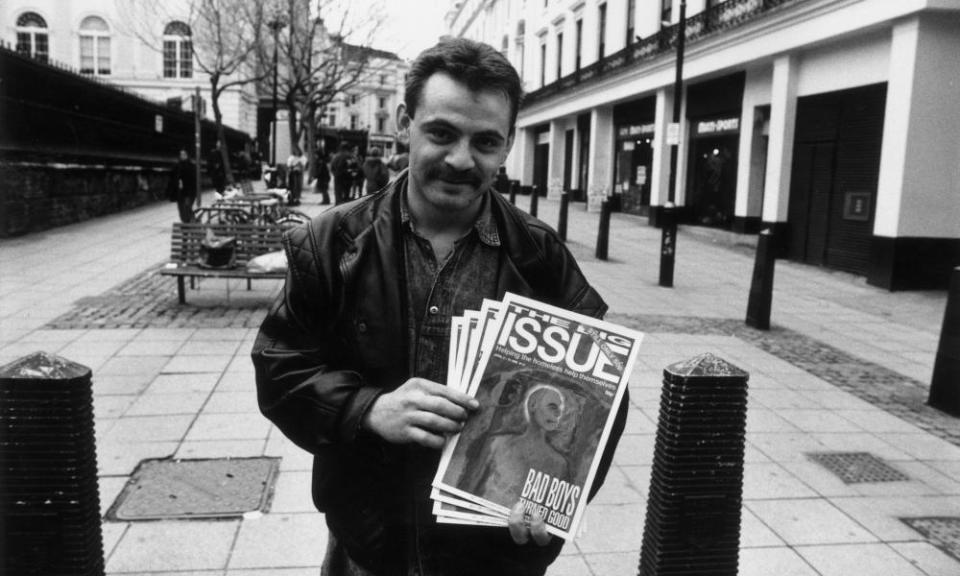

We’d go to places where homeless people congregated and just hang around, talk to them. When we explained that they had to pay for the magazines, they told us to fuck off. But I don’t give up easily and neither does John. On several occasions, we were spat at and the van was kicked. I had to start carrying a baseball bat. Gradually, we gained people’s trust, because we persevered. We were there day in, day out. It just started to snowball.

We work with the most chaotic sales force in the world. We have no idea whether people are going to turn up on a Monday morning or not. They come and go for different reasons, but no matter what else might be happening in their lives, the Big Issue is always there for them. It’s not us that make the magazine, it’s the vendors, out there selling in all weathers. If the public didn’t like them, they wouldn’t buy the magazine. Members of the public really care.

We would never have believed it if you’d told us in 1991 that we’d still be around today, hundreds of millions of magazines sold, one of the biggest street papers in the world. We’d hoped to help get rid of homelessness. But that’s just a pipe dream, isn’t it? Just look at coronavirus – it’s going to wreck the economy, it’s going to wreck families. The Big Issue needs to be around for those people. Our vendors are off the streets right now for the first time in our history. But if the public support us through this, we’ll come back stronger.

• Subscribe for three months at bigissue.com and have the magazine delivered weekly. Half of your money will go to vendors, the remainder will enable the Big Issue to continue its work.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News