Maureen Cleave, Swinging Sixties correspondent who chronicled the rise of the Beatles as John Lennon’s confidante and was the source of the ‘bigger than Jesus’ scandal – obituary

Maureen Cleave, the journalist, who has died aged 87, was a friend and confidante of the Beatles on their ascent to global stardom in the mid-1960s; she famously became John Lennon’s muse and relayed to the world his most toxic quote about the group being more popular than Jesus.

In January 1963 she was a glamorous young pop columnist on the Evening Standard, a fashionable, buzzy paper that chronicled the stirrings of Swinging London through the eyes of writers whose average age was at least a generation younger than the rest of Fleet Street.

A 28-year-old Oxford-educated former debutante, she was the first London journalist to catch on to the Beatles phenomenon, furnishing the group their first major splash in the metropolitan press in a piece headlined “Why The Beatles Create All That Frenzy”, a fortnight after the release of their second single, Please Please Me and their first appearance on ITV’s Thank Your Lucky Stars.

“They wear bell-bottomed suits of a rich burgundy colour with black velvet collars,” she noted. “Their shirts are pink and their hairstyles are French.” She quoted an unnamed Liverpool housewife as saying: “Their physical appearance inspires frenzy. They look beat-up and depraved in the nicest possible way.” This anonymous admirer was Gillian Reynolds, later a distinguished Daily Telegraph columnist, and Maureen Cleave’s best friend at Oxford.

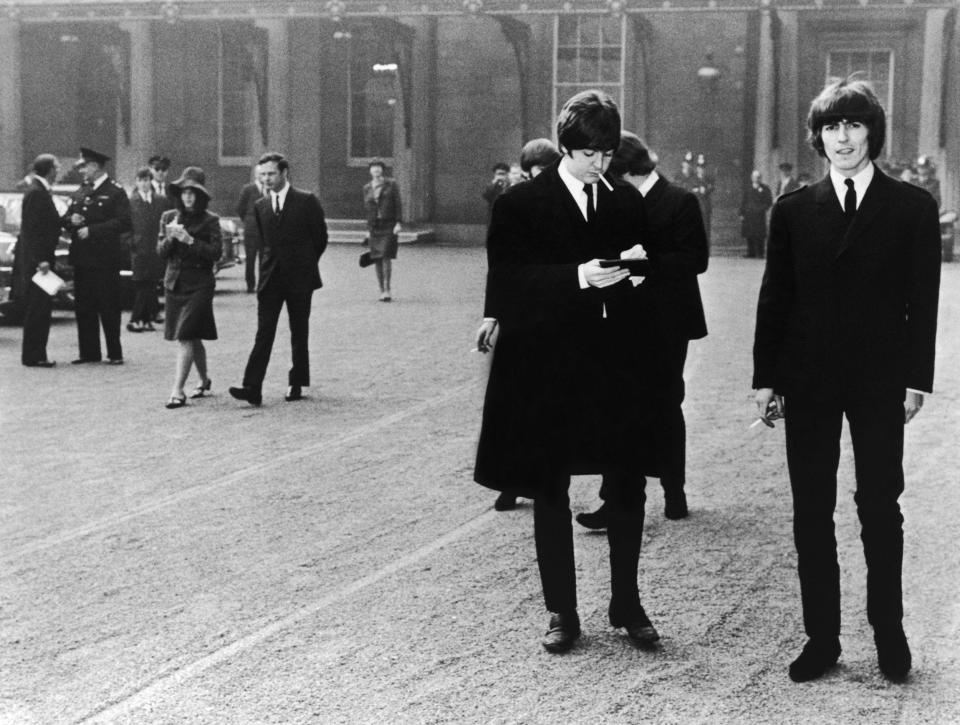

Maureen Cleave was swiftly admitted to the Beatles’ inner circle (where she was known as Thingy), enjoyed privileged access to “the boys” and accompanied them from Liverpool to London for their first concert at the Palladium and in 1964 on their first trip to the United States.

“For two years they were out of breath,” she remembered. “They ran to escape screaming mobs of frightening harpies. ‘Come on, Thingy,’ they’d roar at me as I pelted after them. They were smuggled in and out of food lifts. Once, in America, just like the Marx Brothers, they dashed through a Palm Court orchestra playing to ladies eating ice cream.”

Lennon, for his part, took a particular shine to Maureen Cleave, admiring her intellect as well as her looks – including her red boots by Anello & Davide which were considered rather outré for the time. She wore virtually no make-up and her hair was a natural chestnut colour; it was styled by Rose Evansky, the inventor of the “blow wave”. Lennon likened her prose, meanwhile, to that of Richmal Crompton’s Just William books, a compliment Maureen Cleave claimed was like being compared to Shakespeare.

But once the Beatles had become the most famous entertainers in the world, she witnessed at first hand the destructive force of modern celebrity. When she rang Lennon up at his stockbroker’s Tudor-style mansion in Weybridge, he would ask her what day it was, for the Beatles had long since lost the ability to distinguish day from night.

Whatever the true extent of her relationship with Lennon, Maureen Cleave certainly came to influence his creativity. In 1964 she happened to be interviewing him on the day the Beatles were to record the song A Hard Day’s Night. Arriving in a taxi with Lennon at the EMI recording studio in Abbey Road, she found the tune was already in his head and the words scribbled on the back of a birthday card a fan had sent his baby son Julian.

The lyrics included the lines: “But when I get home to you/I find my tiredness is through/And I feel all right”. Considering this rather feeble and awkward, Maureen Cleave suggested something rather more risqué: “I find the things that you do/Will make me feel all right”.

Lennon agreed the change, and kept it in, giving her the amended written lyric as a memento. After she chided Lennon for only writing songs with one-syllable words, he consciously worked “anybody”, “independence” and “appreciate” into the lyrics of the song Help!

She was reputedly the inspiration for his song Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown), a track on the Beatles’ Rubber Soul album (1965) about a man having an extra-marital affair. Although the number was said to be autobiographical, speculation about the identity of the girl in the song always mentioned Maureen Cleave, among others.

According to one American biographer, Lennon claimed Norwegian Wood was based on a extramarital affair he was having with her and that the song was his work entirely. On the other hand Paul McCartney disputed this, insisted it was written between them at Lennon’s mansion in a single afternoon, and that the fanciful title was a joke about the cheap pine walls in the bedroom of Peter Asher, brother of the actress Jane Asher, whom McCartney was dating at the time.

For her part, Maureen Cleave said that in all her encounters with Lennon he made “no pass” at her, although Lennon, while confessing to his wife Cynthia that he had indeed slept with her (among thousands of other women), later recanted and claimed he could not remember who the song was about. In 2009 Philip Norman in his biography of Lennon revealed it was about his affair with the German wife of the photographer Robert Freeman, who lived in the flat below Lennon and his wife Cynthia when the couple lived in central London.

In the spring of 1966 Maureen Cleave profiled Lennon for the Evening Standard, portraying him as a lazy, restless but reflective and thoughtful figure who was reading widely about religion, and coolly reporting him as saying: “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink… We’re more popular than Jesus now.”

Four months later, on the eve of a Beatles US tour, an American teen magazine picked up the article and headlined the quote, detonating a media firestorm. Beatles records were burned in the Bible belt of the Deep South and outraged local radio stations banned Beatles airplay. The Ku Klux Klan arranged anti-Beatles demonstrations, the Vatican denounced Lennon and Beatles albums were banned in South Africa.

In London Maureen Cleave defended Lennon’s remarks, saying he had merely acknowledged Christianity’s decline in postwar Europe which meant that the Beatles were, to many people, better known than Jesus.

“With a PR man at his side,” Maureen Cleave recalled many years afterwards, “the quote would never have got into my notebook, let alone the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, where it ended up. As it was, the Evening Standard didn’t even put it in the headline. We were used to him sounding off like that and knew it was ironically meant. But the Americans have little sense of irony, and when the article appeared in a magazine, all hell broke loose. It was the last time the Beatles ever toured.”

Maureen Diana Cleave was born on October 20 1934 at Sligo in the north-west of Ireland. In September 1940 she and her mother and sister were bound for India, where her father was an army officer, when their ship was torpedoed by a German U-boat off Rathlin Island. The family spent five hours in a lifeboat before being rescued.

From Rosleven boarding school in Athlone, Maureen went up to St Anne’s College, Oxford, in 1954, and in 1957 took a Third in Modern History, having come out as a debutante in 1955 and been presented at court. Starting at the Evening Standard as a secretary, she had written almost nothing for the paper when the editor Charles Wintour appointed her as a showbusiness correspondent and gave her a column called “Disc Date”.

In January 1963 she wrote about Terence Stamp, a successful young film star from Stepney, aged 25. A week later, her Oxford friend Gillian Reynolds tipped her off about the Beatles, “this odd group in Liverpool who inspired an unaccountable frenzy in the young”, and she travelled north to interview them.

On the train she met the Daily Mail’s star feature writer, Vincent Mulchrone, on an identical mission, and that evening watched the Beatles play a one-nighter at Liverpool’s Grafton Rooms before embarking on a provincial tour supporting Helen Shapiro.

Taken by Brian Epstein to see the queues that had formed two hours ahead of the show, Maureen Cleave was told by some of the girl fans that they had not bought the Beatles’ first single, Love Me Do, in case the band became famous and left Liverpool.

By 1966 they were the most famous foursome on the planet, and Maureen Cleave interviewed each of them in turn for a series in the Evening Standard called How Does A Beatle Live?, concentrating on their home lives and their detachment – particularly Lennon’s – from reality. Opening with her opinion of his personality in a single sentence – imperious, unpredictable, indolent, disorganised, childish, vague, charming and quick-witted – her profile of Lennon still stands as his most famous interview.

When her piece appeared in the Standard in March 1966 Lennon’s “bigger than Jesus” remarks went virtually unnoticed in largely godless Britain. But because of the incendiary reaction when the article was syndicated in the US the following summer, resulting in death threats and genuine fear, it has featured in every biography of Lennon and the Beatles since, and its influence on the group itself can scarcely be overestimated. It was, as one American writer noted, the greatest blow to the Beatles’ favourable image in the group’s history.

Although Lennon expressed regret for any offence caused by his remarks, he declined to withdraw them. Maureen Cleave even offered to take the blame, and to say that she had made up the quotes. Perhaps unwittingly, she changed the rules of engagement of pop music journalism, replacing the traditionally anodyne encounter between press and pop star with a more probing style and casting Lennon in the role of spokesman for a generation. A new type of journalism would soon emerge that reflected this change: when Rolling Stone magazine first appeared the following year, its cover star was John Lennon.

Maureen Cleave severed her links with Lennon shortly after the controversy in 1966, the year she married. “It was exhilarating while the novelty lasted,” she wrote many years later, “though Lennon, far from being surprised and grateful, seemed rather nettled he hadn’t been famous sooner. ‘I was always surprised I wasn’t a famous painter. I used to look in the paper and half expect to see my photograph there.’ He found his own story, the Beatle story, romantic; he liked to talk about the rags and the riches and, by the time they reached the top, fame had so cut them off from real life there wasn’t much else to do but talk.”

Ten years after Lennon’s murder in New York in December 1980, Maureen Cleave wrote an affectionate memoir of him in The Telegraph Weekend Magazine. “Once or twice I had been tempted to call and see him. What had happened to my old friend? Friend, buddy and pal, as he used to say.” But after the “bigger than Jesus” debacle, she admitted that he might not have been keen to see her.

At the Evening Standard she conducted frequent interviews with other famous musicians of the 1960s, including Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones, memorably posing the question: “But would you like your daughter to marry one?” The satirical magazine Private Eye guyed her as Maureen Cleavage, often linking her to a fictional pop group called the Turds, and their charismatic leader Spiggy Topes, based on the Beatles and John Lennon respectively.

Over the next 40 years she continued as a distinguished interviewer of people in all walks of life for the Telegraph and Saga magazines among many others. In August 1992 she collapsed on the platform at Tottenham Court Road tube station with symptoms later diagnosed as ME (myalgic encephalomyelitis, or chronic fatigue).

She married, in 1966, Francis Nichols, an economist and farmer, whom she met at Oxford and who predeceased her in 2015. They had three children.

Maureen Cleave, born October 20 1934, died November 6 2021

Yahoo News

Yahoo News