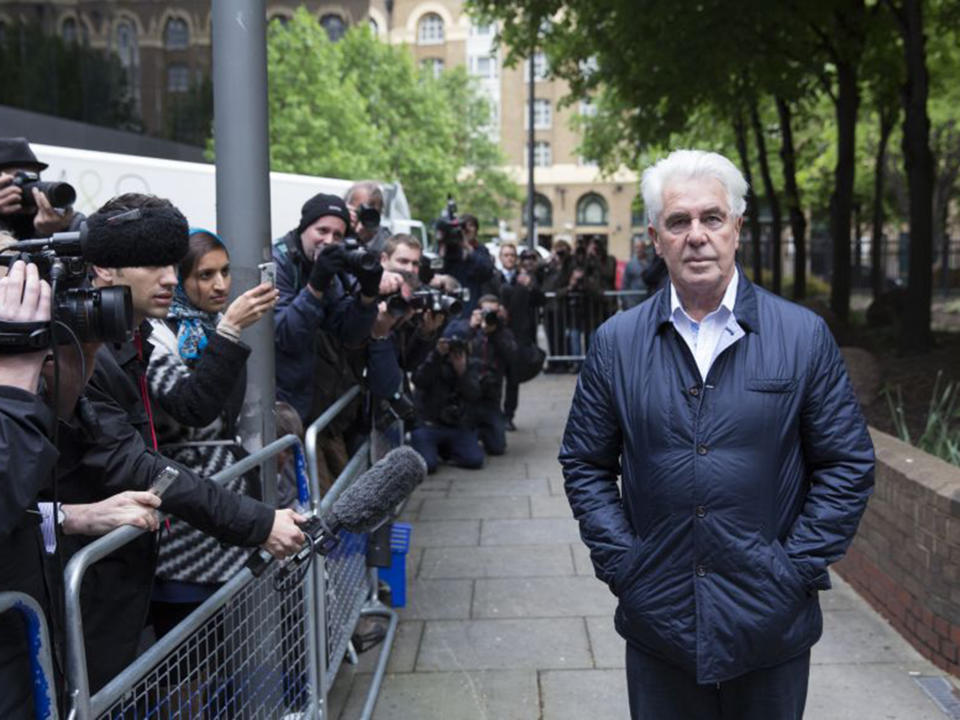

Max Clifford, whose aggressive brand of PR so often replaced real journalism, had a deeply ironic downfall

Max Clifford’s death at the age of 74 brings to an end the life of a man whose impact on the British media is hard to overestimate.

There was a time when Clifford was not only of vital importance to the countless celebrities he represented, but also to the tabloid editors who came to rely on him as a source for stories. He could make careers, and he could break them – and he frequently did both.

Such was his influence that few would have predicted his downfall, least of all the man himself. Yet when he was arrested in 2012 as part of the Operation Yewtree investigations into historic sex offences, the master of media spin was unable to lie his way out of trouble. Just over a year and a half later, Clifford was convicted of eight indecent assaults and sentenced to eight years in jail. He was in the midst of planning an appeal when he died, protesting his innocence to the end.

The effect of Clifford’s crimes on his victims was personal horror. One, abused from the age of 15, wrote that she would give him an “A+ in grooming children”; another said that she shuddered whenever she thought of him.

His effect on British cultural life, thanks to his nexus with the tabloid press, was almost as grim. Not only did his aggressive brand of PR come to replace actual journalism, with editors effectively being drip-fed stories straight from Clifford, but his disregard for the truth meant that the regular publication of false stories became de rigueur.

Most famously, Clifford told the Sun to go ahead with its “Freddie Starr ate my hamster” story in 1986, despite knowing that it was untrue. Starr, his client, was informed that the splash would be good publicity in the run-up to a UK tour.

If that example was harmless, countless others were not. When Clifford helped Antonia de Sancha to sell her story of an affair with Conservative MP, David Mellor, he invented key details to make the tale seem juicier – notably the claim that Mellor had worn a Chelsea shirt during sex.

News of the affair was enough to ruin Mellor’s marriage and, ultimately, his career. But it was the made-up elements at the periphery which left him utterly humiliated. As for de Sancha, exposed as Mellor’s mistress before telling her own Clifford-inflated version of events, the entire episode left her contemplating suicide.

For Clifford – and for the hacks who thrived on his murky way of doing things – people’s lives were simply a means to a stunning headline or a bumper bottom line. His business was built on the commodification of individuals, their feelings relevant only inasmuch as they added emotional ballast to a story. In the heady tabloid days of the 1980s and ‘90s, the appetite for juicy material was ravenous and Clifford was on hand to supply it.

In 2002 he agreed to take part in a Louis Theroux documentary, which saw him engineer negative press stories about the film-maker even while the programme was in the process of being made. Clifford, it seemed, delighted in what he saw as a game of one-upmanship, in which Theroux’s privacy became a battleground.

For years Clifford had a close relationship with the News of the World and the Sun, although he fell out with Andy Coulson, then editor of the former, in 2005. In the years that followed, stories about his clients continued to appear in the Sunday title – a result, it later turned out, of Clifford’s phone being hacked.

This, really, was the ultimate irony: not just that Clifford became an unwitting source for stories he wasn’t controlling, but that he fell victim to a culture of tabloid excess and intrusion which he had for years encouraged and then dined out on.

At the Leveson Inquiry into the culture, practices and ethics of the press in February 2012 Clifford pompously described phone-hacking as a “cancer”. Yet the truth is it was men like Clifford who had helped it to gain root by creating the expectation that private information (some of it unbelievable precisely because it wasn’t true) was acceptable front page fodder.

Clifford will be mourned by his family and by a few old friends (and clients) from the days when he ruled the tabloid roost. But the women who he abused will not grieve.

And in 2017, as the world obsesses about the rise of fake news, we would do well to remember that in the mainstream media, there is far less of it about now than when Clifford was in his pomp.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News