Maxine Peake on Hillsborough drama Anne: ‘It’s a privilege to be a part of something like this’

Maxine Peake remembers the day she got the call from her agent. “He said: ‘A script has come in. It’s about Anne Williams, the Hillsborough campaigner, and… ’ and straight away,” Peake says, “I got in there and said: ‘Yes!’ My agent said: ‘Don’t you want to read it first?’ I said: ‘Oh, all right, then… Can’t we just get cracking on it?’”

Peake had seen Anne Williams on the news, campaigning for justice for her teenage son Kevin, who died at the Hillsborough football stadium disaster in 1989. But she never met Anne, who died in 2013. Soon, the doubts set in. “I sat back and thought: ‘Can I play her? I don’t look like her, I don’t sound like her, Anne’s a mother…’ [As an actor] you think of all the things that you’re not. But then I just thought: ‘This is not about me, it’s about telling a story. It’s about the privilege of being a part of something like this.’”

It’s early December, and Peake, her co-star Stephen Walters and scriptwriter Kevin Sampson are talking to me via Zoom about Anne, ITV’s new dramatisation of the life of Anne Williams, a shopkeeper from Formby who spent 20 years battling the Hillsborough cover-up and grew into one of the most inspirational justice campaigners of the late 20th century.

Anne airs over four consecutive nights in January, a drama that spans 24 years, from 15 April 1989 to Williams’s premature death from cancer in 2013. It’s a powerful portrait of an unassuming mother and her fight for the truth – and the toll it took on her family and her health.

Made by World Productions, the team behind Line of Duty, Vigil and The Pembrokeshire Murders, Anne was written and conceived by Sampson, an author and Liverpool fan who survived the crush outside the Leppings Lane end at Hillsborough, then witnessed the tragedy unfold inside.

At the heart of his adaptation is what Sampson rightly describes as a “phenomenal” performance by Peake. “It’s one of the reasons I do what I do, to be involved in projects like this,” Peake tells me. “I had so many actors calling me, saying: ‘Can you get me a scene in this?’ Actors who would never normally do this.”

Anne begins with 15-year-old Kevin Williams waking up on a sunny spring day in 1989 to his mum telling him that he can go to the FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest after all, and follows her through the two decades during which she confronted police lies, political corruption and a sneering judiciary to secure the rightful inquest verdict into how he died at the match. Much of Anne is painful to watch – some scenes will have viewers shouting at their screens in frustration – but it’s subtle, too; an inspiring story about a mother’s love for her family, and how goodness can endure in people exposed even to the most cynical power in the land.

“It’s deeply harrowing in parts,” Sampson says. “But it has to be that way. When I first mentioned the idea of doing a film to Anne [back in 2012, when Sampson was writing the book Hillsborough Voices] I told her that compared to what she had been through, Erin Brockovich was light entertainment.”

For all the bereaved mums, their job description changed overnight… they became truth-seekers, detectives, campaigners

Kevin Sampson, scriptwriter

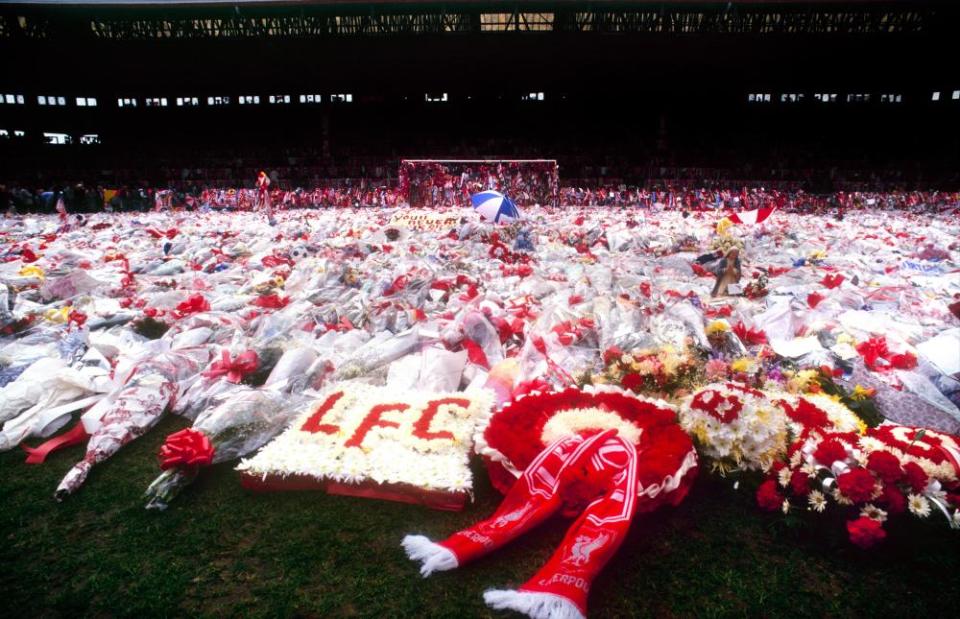

Kevin was crushed to death in pen 3 at Hillsborough: one of 37 teenagers among the 97 men, women and children killed by catastrophic police negligence. In episode one, Peake plays Anne in the first year of her bereavement; poleaxed by grief, buried under the bedsheets, pushed from pillar to post simply trying to establish what happened to Kevin in his final moments.

Anne initially believes the official line that Kevin died rapidly, of compression asphyxia – that there had been no chance of him being saved once severe neck injuries were inflicted. While at first she takes some solace in the belief his death was instantaneous, by the second episode, in 1990, cracks are starting to appear in the official narrative. As Anne begins to piece together the truth, with the help of lawyers, medical experts and two police officers who refuse to toe the line, Kevin’s death emerges as one of the keys to a cover-up.

At the original Hillsborough inquests in 1990-91, the coroner, Stefan Popper, imposed the infamous “3.15 cut-off”: essentially, Popper ruled that all those who died had received fatal injuries that were irreversible by 3.15pm. Thus there was no need to hear evidence into the emergency services’ response beyond that time.

In 1990, Popper’s ruling was largely taken at face value. But over the four episodes of Anne, which follow her campaign from 1990 to 2012, it becomes evident that the South Yorkshire coroner’s ruling meant the full extent of the South Yorkshire Police negligence at Hillsborough, under Chief Supt David Duckenfield, was never scrutinised in Sheffield Town Hall. It took the Hillsborough Independent Panel’s landmark report, in 2012, to establish that if there had been a properly coordinated emergency response, Kevin – and 40 others who died that day – might have been saved after 3.15pm.

The wider truth was not, initially, Anne’s concern; she simply wanted to know what happened to “my little boy”. “So many of the campaigners were heartbroken mums in search of answers,” says Sampson, “and the idea of a mother’s love as the most potent adversary to corruption is a powerful one. It’s also completely relatable.”

The relatability is also there in the depiction of a family breaking down in their grief, and their need for truth. While Anne and her indefatigable ally Sheila Coleman, a researcher from Liverpool city council, become amateur sleuths (“They used to describe themselves as Cagney and Lacey,” Sampson says), Anne’s husband, Steve, pleads with her not to describe Kevin’s fatal injuries to their elder son over tea, despairs over family holidays ruined, and looks on hopelessly as his wife drifts away, physically and emotionally. As Steve begins to realise family life will never be the same again, he retreats into the garden shed with his record player. One night, as Anne is drinking in a Kilburn pub after an encounter with the high court, Steve packs up his record collection and moves on.

As Sampson says: “For Anne and all these bereaved mums, their job description changed, unbidden, overnight. When they woke up on that Sunday in April 1989 they were truth-seekers and detectives and campaigners. Viewers will, I think, empathise with that – seeing the little people rise up in adversity to become mighty.”

When he first mooted the idea of adapting her story in 2012, Sampson was losing his own mother. “I felt inspired to write about these doughty mums, rolling up their sleeves.” Among all the bereaved Hillsborough mothers, why Anne? “Of all the people I’ve met, she was the one who best embodied the humility, the determination and the humour,” he says. “Anne embodied the universality of the Hillsborough experience.”

* * *

Anne was a friend of mine. I survived the crush in pen 3 that killed Kevin, and in 2009, on the eve of the 20th anniversary of the disaster, with the cover-up stretching endlessly ahead, I wrote a story for the Observer about my experience of surviving Hillsborough, and how others had been affected – including Anne. We became friends, as Anne did with so many survivors. I tell Peake that her performance is remarkable – all the more so for the fact that she never met Anne.

She smiles, sweetly. “Ah, thank you. You can’t help but go out with your fingers crossed that people see some resemblance to Anne, and who she was.” What did she draw on? “As an actor, you’ve got your instinct and your empathy. I also read Phil Scraton’s book Hillsborough: The Truth, Kevin’s Hillsborough Voices, I watched archive news footage, and met [Anne’s daughter] Sara. But at the end of the day, you go with the words on the page.”

Sampson’s script is subtle and, for all its pain, free of sentimentality – something that appealed to Peake. “Right at the start,” she says, “I said to [the director] Bruce Goodison: ‘I don’t want this to be too sentimental. I don’t want Anne to be in tears all the time… ’ Anne reminded me of my mum: that generation of understated, quiet women who weren’t political but had a strong sense of justice.”

Peake lost her mum to pancreatic cancer at 66, six months after she was diagnosed. “I saw her cry [only] once,” she says. “Those women didn’t… You see lots of dramas now and everybody’s always crying! And I actually think it takes a lot for real people to cry. We cry at not the most tragic things, sometimes. It’s always surprising, people’s reaction to trauma.”

Anne is indeed a story of trauma, of what Sampson describes as the “collateral damage of Hillsborough”, but it’s a story in which hope endures. It’s there in what Peake describes as “such a beautiful relationship between Anne and her husband, Steve”, played by Stephen Walters (Outlander, Little Boy Blue) in his first role since a stellar performance in season four of Shetland as released murderer Thomas Malone.

Walters had the benefit of being able to meet the inspiration for his character. Steve Williams had become a virtual recluse; content just left alone with his music. To Sara’s surprise, her dad invited Walters to his home.

“It was the guitar, and music, that we bonded over,” Walters says. “Just talking for an hour about blues records. I had a go at his guitar – his hands are not so good now, but you could tell he was a player, and I play too. And it helped; he was really open. He said: ‘Ask me anything.’”

As filming progressed, Walters would listen to Van Morrison’s Into the Mystic “every morning, and evening, as that was Steve and Anne’s song”. And he would text Steve for insights into how he reacted to certain events. “These are things that inform a role, things you could never get from a book,” Walters says.

For Sampson, an Anfield season ticket holder who has lived with Hillsborough since day one, there was “a huge burden of responsibility” in writing the screenplay. “Our country has, in the main, looked the other way while this abhorrent abuse of the most basic human rights has gnawed away at these people, over decades, in plain sight,” he says. “And you don’t want people to look away. Too many people think that those touched by the disaster should put it behind them. I think those people need to know a bit more about why it’s so hard to do that – and the telling of that is quite tough.”

As a survivor, I can see where one or two punches may have been pulled. “I consulted with Anne’s family at every step,” Sampson says, “and if we felt that something was too close to the bone, we’d pull back.”

And yet, frequently, there are moments so moving that the use of archive footage from the day of the disaster comes as something of a relief. Peake and Walters are compelling; spinning round each other in their grief like two dancers in the dark. And at about 9.45pm on 3 January, when the second episode airs, I won’t be surprised to hear the cry of millions across the country: “But there’s an ambulance right there, on their own fucking videotape!”

Was it draining for Peake and Walters, playing Anne and Steve? “No, I find it quite energising when you get to play people like these,” Peake says. “We had the most fantastic conversations with people around the campaign. They were so human, and full of humanity. People like Bishop James [Jones, chair of the Hillsborough Independent Panel] spoke about his spiritualism, and Anne’s spiritualism. And I came away thinking: ‘Wow!’”

Peake describes herself as “a card-carrying atheist”. But sometimes, “maybe there are other elements. Back in the day, actors were shamans, weren’t they… Maybe you get help from other places.”

Walters agrees. “I do believe [in God]. I remember having these philosophical discussions with Maxine about life… and, again, that feeds the work.”

The scripts took Sampson a year to write, and the entire four hours of drama was shot in just nine weeks. “Bruce [the director] got us together three or four days before we started principal photography, and we went over all of the scenes between Steve and Anne, and that wedded us in,” Walters says. “And we hooked up together for a night in Wales before filming the first scene, and just talked. It cemented something before we actually started. There was a sense of us together. It’s not always that a director does this,” he says.

It was a clever approach, given the tight schedule. Peake might be playing Anne in her 30s one morning, then Anne in her 50s that afternoon, and as she wrapped the morning’s shoot she’d be told: “You’re 20 years older after lunch, Maxine.”

Throughout, her ability to capture Anne’s mannerisms, her compassion, her resolve, is extraordinary. Anne’s daughter, Sara, said: “When I first heard that Maxine would play my mum, I thought: ‘Well, she looks a bit like her. But by the end, I felt like I was watching my mum.”

For Peake “it was never conscious. I didn’t watch Anne and go: ‘Oh, these are her mannerisms, I must do those.’ But Anne had a slower rhythm than me, so it was about slowing things down. You have to check yourself sometimes. I would have to say to myself: ‘You’re not feeling sorry for Anne, you are playing Anne.’ You have to navigate your emotions sometimes: it’s a case of ‘Am I in the moment, as Anne, or is this me going ‘This is overwhelming’?”

Scenes shot on the beach at Formby allow for some of the air we all needed to breathe – Anne as she refuses to buckle under her suffocating anguish; the survivors, her allies, struggling with PTSD. There is humour, in parts. But this is essentially a love story, of a mother’s devotion to her family.

It is also a tribute to Anne’s unyielding faith in the goodness of people. In episode one, she is moved by the generosity of a farmer outside Sheffield the morning after the disaster, who refuels their empty petrol tank as she and Steve head into the city to find Kevin. “Most people are good, Anne,” Steve says, as they set off towards Hillsborough, and into a 24-year ordeal.

Related: The great betrayal: how the Hillsborough families were failed by the justice system

Anne’s faith in the good endures the carnival of corruption ahead, even if her marriage can’t. By the end of episode four, we see her at the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand in London, in 2012, to see the lord chief justice quash the original Hillsborough inquest verdicts of accidental death – effectively, Anne’s dying wish. While physically diminished by cancer, she appears a giant of a justice seeker.

As the final credits remind us, no one has served a moment’s jail time for unlawfully killing Kevin and 96 other people at Hillsborough. And yet the truth that Anne Williams helped to establish has become something purer, more enduring than the “justice” delivered by a legal system that became transparent only in its unwillingness to hold the guilty to account.

“Anne was always able to find hope,” says Sampson. “She believed that most people were good, and that the truth would, eventually, out. She was right. That basic belief in the power of truth is Anne’s legacy, and it is, for many of us, the ultimate verdict on Hillsborough. The establishment lied. The ordinary people told the truth.”

• Anne is on ITV on 2 January

• The documentary The Real Anne: Unfinished Business starts on ITV on 2 January

And the Sun Shines Now: How Hillsborough and the Premier League Changed Britain by Adrian Tempany was shortlisted for the Orwell prize

Yahoo News

Yahoo News