MLK should be remembered as a revolutionary thinker – not a sanitised figure for conservatives like Mike Pence to exploit

21 January is dedicated, for the 34th time, to the celebration of Martin Luther King Jr Day in the United States, and this year is particularly special as January 2019 marks 90 years since the activist’s birth.

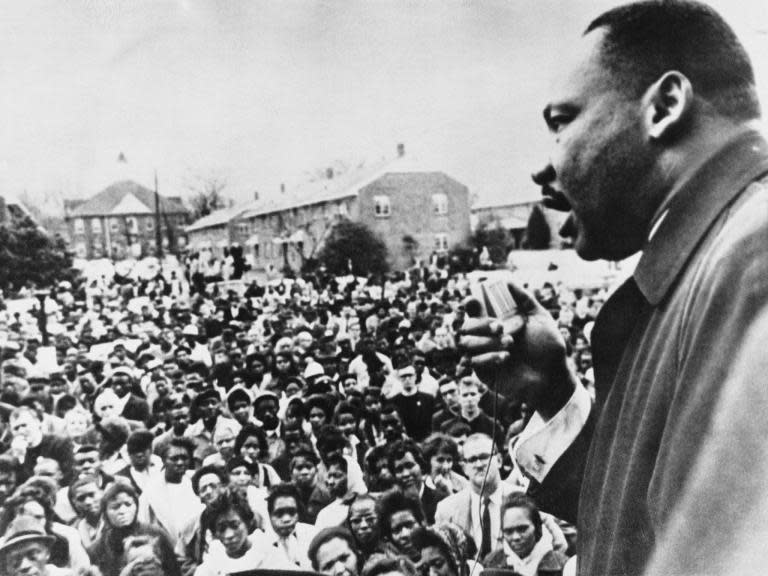

Parades and concerts will be held to honour the memory of the great civil rights leader. President Trump, no doubt, will offer a tweet in recognition of King’s achievement and legacy. Mike Pence has already used King’s words to defend Trump’s border wall.

But the danger of this commemorative day is that it fossilises King, rather than animating him again for contemporary Americans.

Like many media representations of King following his assassination, the holiday risks contributing to what one of his biographers, Marshall Frady, calls a “pop beatification”. In Frady’s words, he is thereby transformed into “a weightless and reverently laminated effigy of who he was”.

To honour King actively on this holiday, then, requires Americans to turn again to his thought and to reflect on the political and moral lessons it continues to offer. Sadly, there is still an urgent need for Martin Luther King Jr in the United States, even though it is now 50 years since his death.

Wary of his many opponents, King did not expect to reach old age. He acknowledged this in his last-ever speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”, delivered in Memphis the night before his assassination. “I’ve seen the Promised Land”, King told his audience, before adding sombrely: “I may not get there with you”.

Interestingly, at the start of his speech, King sought to rectify this likely confining of his life to a small span by imagining he had powers of time-travel and could be transported to other moments in history. This exercise in what he calls “mental flight” takes him from Moses’s parting of the Red Sea to the Depression of the 1930s, via “the great heyday of the Roman Empire”, the Renaissance and Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation at a time of profound division in America in 1863.

King restricts his imaginary time-travelling to reverse mode, journeying only to various phases of the past. But what if he were to be projected forwards instead? How might King reflect if relocated to a later era of national disunity, the US as currently stands under President Trump?

While King is noted for his utopianism (notably the vision of a colour-blind America articulated in his “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, D.C. in 1963), his last years were frequently shot through with darker thoughts about his country. “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”, for example, initially conjures up a disturbing scene: “The nation is sick, trouble is in the land, confusion all around”. It is difficult to imagine that the judgment on America 2019 of a teleported King would differ from this in any significant respect.

Another socio-economic diagnosis by King, in a speech after receiving an honorary degree at Newcastle University in 1967, also remains timely: “There are three urgent and indeed great problems that we face today…That is the problem of racism, the problem of poverty and the problem of war”. These three problems, tangled together as they were for the later King, persist in the US and around the world today.

With regard to “the problem of war”, there are, perhaps, some hopeful signs, as in Trump’s inclination to withdraw US forces from some theatres of conflict and his contacts with North Korea.

However, to place hopes for lasting peace in a president whose energy source is the striking of aggressive, oppositional poses would seem foolish.

Trump’s interventions in the field of race relations have tended to soothe rather than challenge a white supremacist outlook. Consider his vitriol against African-American footballers who, in protest against a wave of black deaths at the hands of police officers, have opted to “take a knee” rather than stand during the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner”.

Or recall the moral equivalence he drew between far-right agitators and anti-racist protesters after events in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017.

A later feature of King’s thought was sensitivity to class inequality as it pertained to combating institutional oppression. “I choose to identify with the poor”, he told his Atlanta congregation in 1967: “I choose to give my life for the hungry”. Surveying the deeply unequal American scene in 2019, the latter-day King would, unfortunately, find continuing cause for his martyrdom.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News