We should mourn the death of the teenage summer job

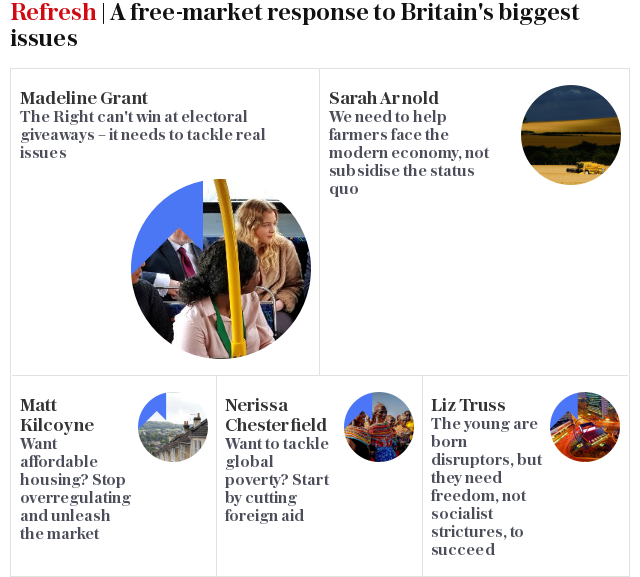

Welcome to Refresh – a series of comment pieces by young people, for young people, looking for a response to Britain's biggest issues

Like many young people, I did a number of part-time jobs in my late teens – some good, some bad, and some very ugly indeed. There were summers pulling pints at the local pub, tennis coaching, ad hoc babysitting and tutoring – even a wildly unsuccessful stint as a cold-caller (never again!). But if recent developments are anything to go by, this experience would put me in the overwhelming minority today.

Teen employment has plummeted over the last two decades.

Back in 1997, 42 percent of 16-17-year-old students were studying and working – a figure which had declined to 18 percent by 2014. There has been a sharp recent decline of younger teenagers in work. Employers must apply for a license to hire anyone under 16, and the number of child employment permits declined from almost 30,000 in 2012, to around 23,000 in 2016.

A desire to focus on study was the dominant reason for not combining work and education

It’s fair to say that the good old-fashioned summer job has taken a battering in recent years, but what has been driving these changes? More fundamentally, should we mourn the decline of this institution, once a rite of passage to so many youngsters?

The increasing demands of school exams and growing pressure from teachers and parents are obvious and important factors. One recent survey of teenage students found that a desire to focus on study was the dominant reason for not combining work and education – according to 55 per cent of respondents.

Hardly surprising, perhaps, when teens are bombarded with the message that a galaxy of “A-stars” is essential to future success, and many schools, their eyes fixed on the league tables, actively discourage pupils from getting jobs during term time.

Surveys and vox-pop interviews suggest that increased parental affluence has contributed too - more pocket money means less financial pressure to work. Meanwhile, traditional “children’s jobs” like newspaper rounds have declined rapidly.

This is partly linked to changing consumer habits (far fewer of us get milk or newspapers delivered to our homes) and the automation of low-skilled jobs, yet overzealous government regulation has also stifled the availability of these jobs to young people.

Our regulatory approach is hugely complex, varies considerably from area to area, and has become gradually more stringent in recent years, for example, with rules on term-time working tightened for under-16s.

Certain jobs like milk deliveries, once staples of teenage employment, are now forbidden outright by some local authorities, and since anybody working with young people must now be checked by the Disclosure and Barring Service, while workplace health and safety regulations have also been tightened, small businesses, in particular, may well find it too much trouble to take youngsters on.

Regulation impinges in other areas too: tighter rules on newspaper weights, the selling of alcohol, tobacco, knives and various other goods mean that under-18s can’t do many of the retail and delivery jobs they once could. Compulsory work experience for schoolchildren, which often led to part-time jobs, was scrapped in 2012, and this has probably not helped.

Perhaps most worryingly, few employers, children, teachers or parents show much awareness of the rules governing teenage employment, which, in practice, represents a further barrier to entry.

If we can’t trust young people with a Saturday job – or even a pint – why on earth should we trust them with a vote?

Businesses who might offer work may be deterred for fear of getting it wrong, or because the rules they do understand are inflexible. Given all of the above, it’s hardly surprising that most experts agree that the majority of child employees are probably working illegally.

No doubt many well-meaning people will be glad to see the back of teenage jobs, perhaps viewing weekends as best kept for study and socialising – or even fearful of Dickensian “worst case scenarios” involving child miners and chimney sweeps.

Yet it’s perhaps ironic that, alongside this long-term trend away from part-time work (and a raft of other legal changes which have pushed up the age at which the state recognises you as an adult), “progressive” political parties in the UK are largely supportive of extending the franchise to 16-year-olds. If we can’t trust young people with a Saturday job – or even a pint – why on earth should we trust them with a vote?

As a former devotee of the summer job, I hope these trends will soon be reversed. Moderate working when young builds confidence, self-esteem, a sense of responsibility and other basic life skills essential to later life. Crucially, it can give future employers more of a basis for taking you on, helping to mitigate the vicious cycle facing so many university leavers – the eternal "can't get a job without experience, can't get experience without a job” conundrum.

This is borne out in the data too; young people who combine work with full-time education are markedly more likely to be employed five years later – and earn 12-15 per cent more on average, than those who do not.

While youth unemployment is thankfully much lower here than in most of Europe, it remains far too high. We often hear that the best quality learning a young person can receive to improve employability is to have a ‘real’ experience of work - and yet UK policymakers have consistently raised the hurdles to youth employment.

Mounting data from New Zealand – a country which takes a much more permissive approach to youth employment – suggest that youth employment has few negative side-effects in other areas of life.

A recent longitudinal study looked at the lasting effects (up to age 32) of schoolchildren’s paid work on a wider range of factors than future employability. These included psychological wellbeing, smoking, drug and alcohol use. Its lead author concluded that moderate levels of part-time work seemed to have no detrimental effects in New Zealand. It seems very likely that the same applies in the UK.

The evidence is clear, although the panic of exams and parental pressure may prove hardest of all to conquer. For what it’s worth, I always found my summer jobs – particularly the monotonous ones – a huge incentive to work harder at school and university. After all, there’s nothing like a boring job to push you to get a better one.

For more from Refresh, including debates, videos and events, join our Facebook group and follow us on Twitter @TeleRefresh

Yahoo News

Yahoo News