Shorter, slower and fewer key changes: How number ones changed over 70 years

UK number one singles have become shorter, slower and more likely to boast a diverse line-up of performers but once-familiar elements such as key changes and fades have almost completely disappeared, new research shows.

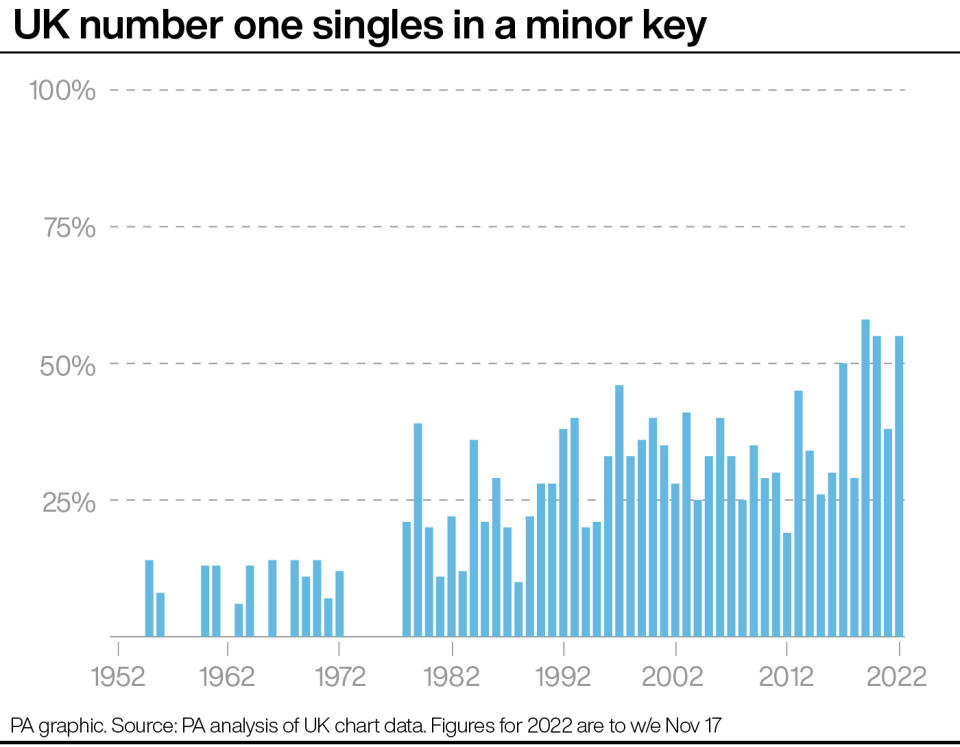

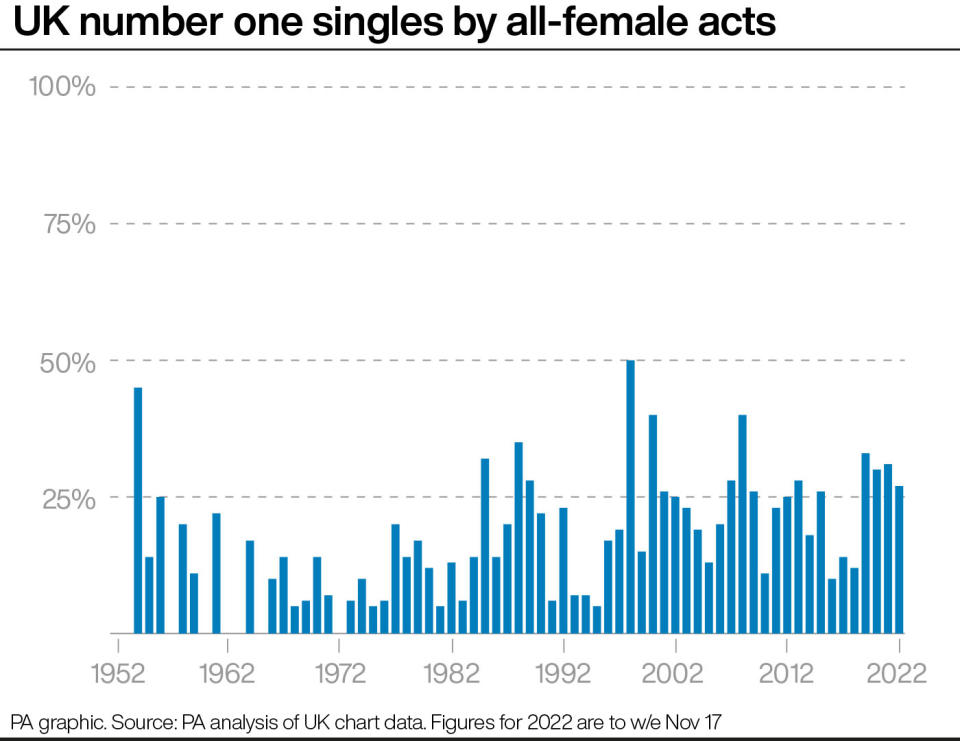

The singles chart celebrates its 70th anniversary on Monday and while some characteristics have barely altered over time – females are still outnumbered by male and mixed acts – there has been a long-term trend towards more hits in minor keys, while time signatures are increasingly four beats in a bar.

Changes in taste help explain some of the findings, though “the advance of technology and new ways of working in music” are also likely to be responsible, experts said.

The PA news agency analysed all of the 1,404 releases to reach number one from the very first, Here In My Heart by Al Martino, to the latest, Anti-Hero by Taylor Swift.

The research shows:

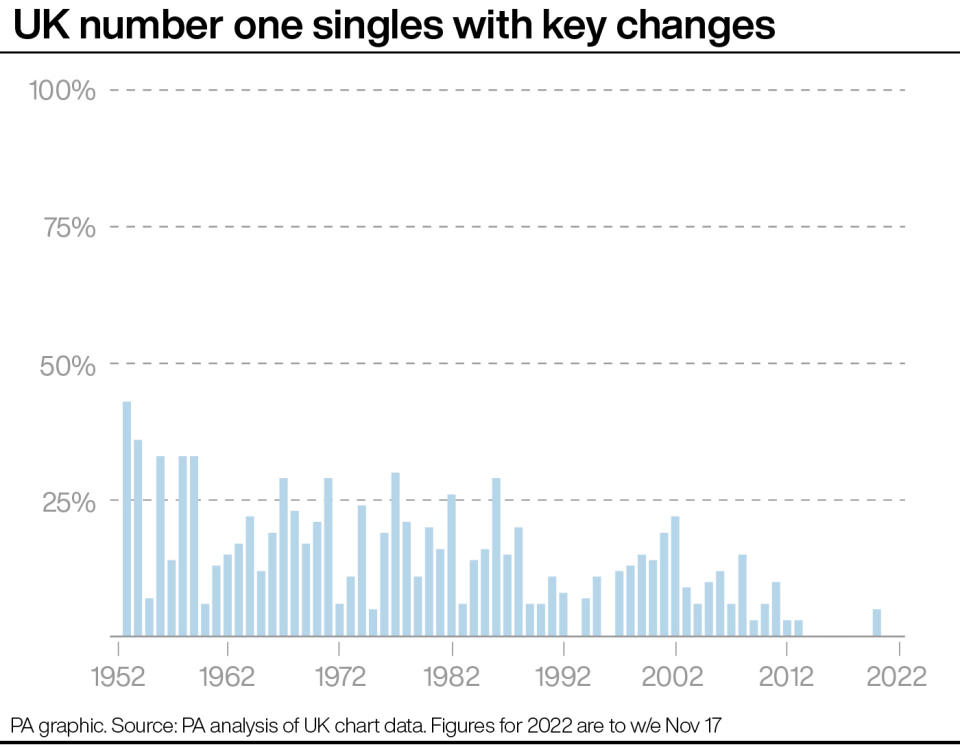

– Key changes were used on nearly half (43%) of number ones in 1953 and remained common through to the 1980s, appearing on nearly a third (29%) in 1986. However they are now incredibly rare, with just one example in the past nine years – the cover version of You’ll Never Walk Alone by Michael Ball and Captain Tom Moore in 2020.

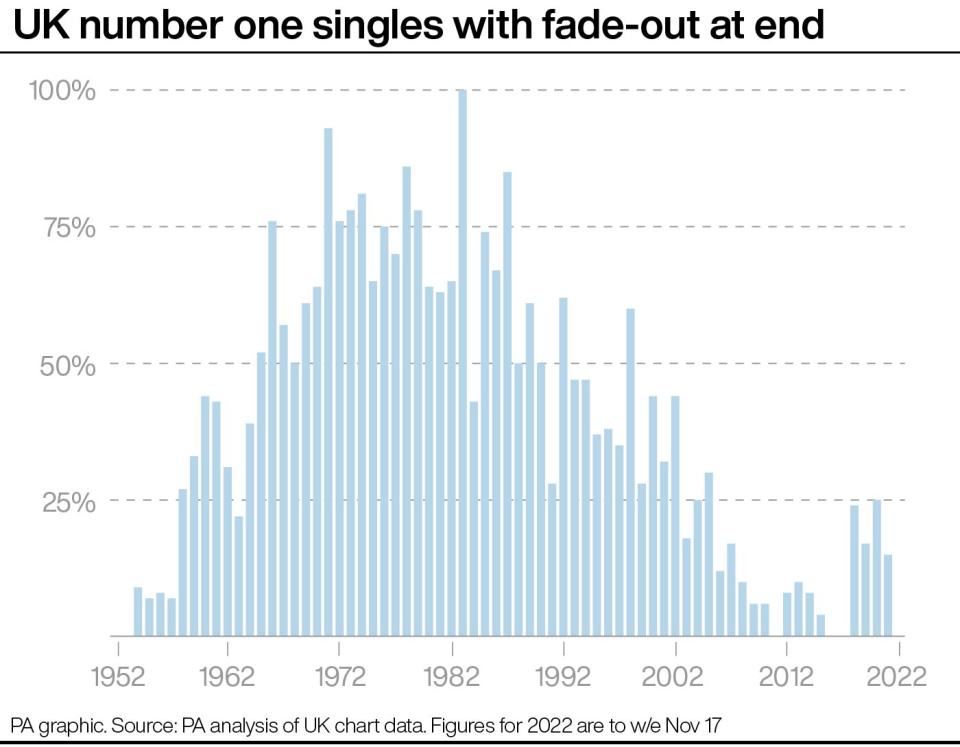

– Fade-outs have faded out of fashion, from appearing on 93% of number ones in 1971 and 100% in 1983, to none at all in 2011 and on only 23 since then.

– Also facing extinction are number ones with time signatures in anything other than a strict four beats in a bar, with just 13 of them so far this century – the most recent again being 2020’s version of You’ll Never Walk Alone.

– Played back-to-back, the 1,404 number ones, including double A-sides, take nearly 85 hours to hear in full.

“Many changes are due to the advance of technology, which has upended previous ways of working in music production and composition,” according to chart analyst and historian James Masterton.

“When you are doing it organically by playing live instruments, your instinct is to change things up a little to stop a song becoming tedious – and once upon a time that meant changing key. Now everything is on a computer screen you can be more subtle and shift the harmonics instead.”

Fade-outs were once necessary “thanks to the limitations of the vinyl format”, he continued, “and it is only in the digital era, when everything is online and streamed, that songwriters and producers have properly discovered the art of ending a song with a flourish.”

Tim Wall, professor of popular music at Birmingham City University, said the findings reflect how there has been a long-term move away from “classically trained professional songwriters providing hits for artists, to self-composing groups – such as The Beatles – and then to people who create music on technology which they can control, who don’t ever think they need to change the key.”

Trends in number ones can be affected “by something bursting through, as if like magma underneath a volcano, being bright and disruptive – but there are also blockages and obstacles that prevent a whole reservoir of music getting to the top,” he added.

One example is the average speed, or tempo, of number ones, which increased sharply in the late 1950s, when rock and roll broke into the mainstream, and again in the early 1960s, driven by the success of The Beatles and other guitar groups.

But tempos have since been on a broad downwards path, with neither punk in the 1970s or dance music in the 1980s having enough of an impact to halt this trend, while recent years has seen the average drop even further.

Number ones reached an average of three minutes in length by 1967 and four minutes by 1984, before starting to get shorter in the late 1990s and are now close to three minutes again.

One reason for this is “songs have lost their intros, with streaming to blame,” said Mr Masterton.

“You only get paid – and a play only counts for the charts – if the listen lasts longer than 30 seconds. People will still not sit through a song they don’t like, so production is now focused on getting to the meat of the song as quickly as possible, to hook the listener in.”

There has yet to be a year when all-female acts have enjoyed a majority of chart-toppers, despite multiple hits from the likes of Madonna, the Spice Girls and Adele – the closest being a 50-50 split in 1998.

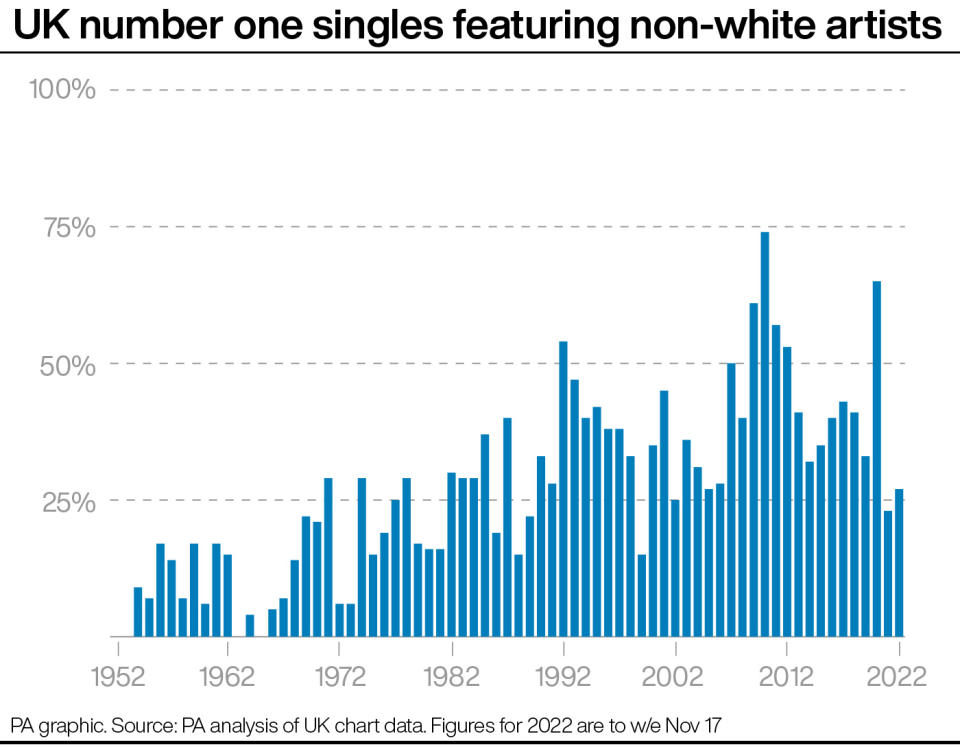

But while they have become more diverse in terms of ethnicity, there have only been six years when number ones by mixed/non-white acts have outnumbered all-white artists, five of them since 2009.

“Britain is becoming a more diverse country, but the crossover is still important: that moment when white audiences start to pick up music from another genre, whether reggae in the 1970s or grime more recently, and that can take time,” Prof Wall said.

Meanwhile there have been only three years when songs in minor keys have outnumbered those in major keys, all of them recent: 2019 (58%), 2020 (55%) and 2022 so far (55%).

This could reflect periods of “economic downturn”, suggested Mr Masterton. However, care is needed when looking for connections, Prof Wall said, as “change can come as the result of the preferences of record buyers, or because of what they are given to choose from – or, more usually both.”

Over its 70 years, the singles chart has evolved from a top 12 launched by the New Musical Express in 1952, to a top 50 prepared by the British Market Research Bureau in the 1970s, to the top 100 currently produced by the Official Charts Company.

“Something that’s lasted this length of time, and that tells us something about change in society, is a really valuable thing,” Prof Wall said, adding: “The charts are sometimes dismissed as trivial, but they’re not trivial for the people who buy these records, it’s absolutely central to their lives, and I think we do them and ourselves a disservice by treating it in that way.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News