Nelson Mandela's unpublished prison letters are full of life and love

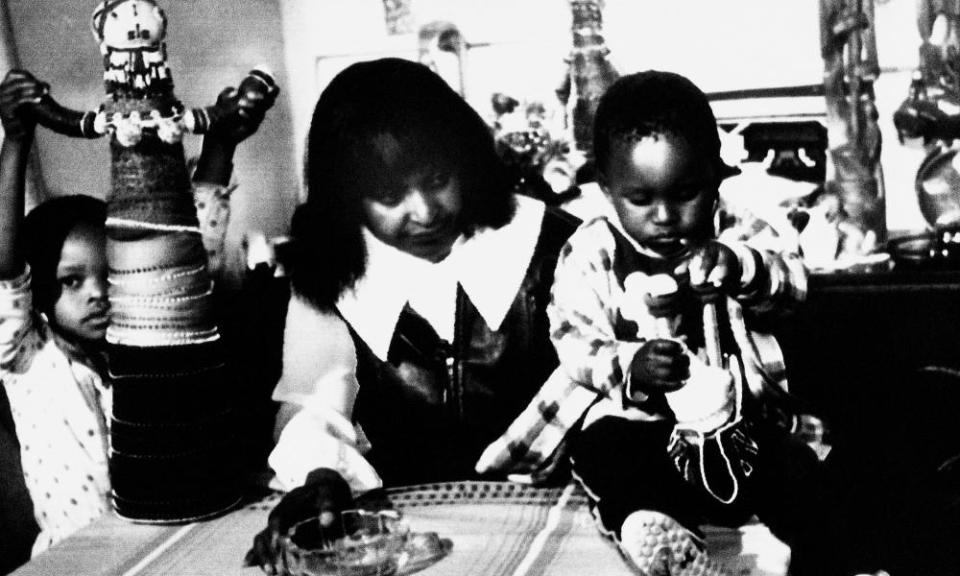

Photograph: Ulli Michel/Reuters/Corbis

In 1969, six and a half years into his 27 year imprisonment, Nelson Mandela wrote to his wife, Winnie: “Since the dawn of history, mankind has honoured & respected … men and women like you darling – an ordinary girl who hails from a country village hardly shown in most maps.” The letter is one of many he wrote to Winnie and it is his love for her that lights up the pages of this mesmerising book of prison letters, many of which have not previously been published.

He had been sentenced to life at a time in South Africa’s history when life meant life, and at first was only allowed to write one 500-word letter every six months, and then only to family members. He wrote drafts in the hardback notebooks he kept in his cell (and at one time was furious that two of these, along with a precious pen, had disappeared). Because the prison authorities would delay his letters – sometimes not sending them – and would hold up or confiscate replies, he never knew whether they’d been received. On one occasion, when he realised that someone had not got his letter, he painstakingly recopied it exactly as it had been a decade before. Thus does time pass slowly in prison.

Nelson Mandela was an icon in his time and has been mythologised since his death as the man who brought peace to a country and made forgiveness on a grand scale seem possible. His voice, brought to life in these letters – which are being published to celebrate the centenary of his birth – helps the reader understand why: his writing pulsates with a conviction allied to a humanity that helped lay the grounds for the miracle of South Africa’s peaceful transformation. At the same time, we are given a privileged glimpse into just how much this one man, and his family, suffered for that transformation.

The year of his letter to his “ordinary girl” stands out as one of the most terrible of all his years of imprisonment. Winnie, his contact with the world, was herself in prison, awaiting trial, leaving their children “orphans”. His mother had not long since died and he had not been allowed to go to her funeral, a loss that stayed with him for a very long time. In a number of letters, some of them written years after the event, he describes his mother’s visit to him, and his last sight of her as she walked from the prison towards the boat that would take her to the mainland, and his sudden feeling that he would never see her again. Reeling from her loss, he was handed a telegram telling him that his 24-year-old son, Thembi (by his first wife Evelyn) had died in a car accident. He describes how his blood turned to ice and how he eventually found his way back to his cell which was, as he writes: “The last place where a man stricken with sorrow should be.” As with his mother, he was denied the chance to bury his son or to visit his grave. Achingly, he writes about his last sight of Thembi in 1962:

Then he was a lusty lad of 17 that I could not associate with death. He wore one of my trousers which was a shade too big for him … He had a lot of clothing, was particular about his dress & and had no reason whatsoever for wearing my clothes. I was deeply touched for the emotional factors underlying his actions were too obvious. For days thereafter my mind & feelings were agitated to realise the psychological strains & stresses my absence from home had imposed.

Before we also had to leave home, both my parents, Ruth First and Joe Slovo, had worked closely with Mandela: Joe and Mandela had together formed the ANC’s nascent army. Joe went into exile around the time of Mandela’s jailing, and only returned in 1990 as part of the ANC negotiating team, before becoming Mandela’s first minister of housing after the 1994 election. A year later, when Joe died of cancer, Mandela was our first visitor. He sat opposite us, Joe’s three daughters, and, in the quiet of a breaking dawn he told us how his only regret was that his children, and the children of his comrades, had been the ones to pay the price for their parents’ commitments. I thought at the time that he was doing what he was so good at – seeing us and acknowledging our loss – but now, reading these letters, I understand how deep ran this regret.

Death stalks these letters

Here he is, writing to a relative in 1971: “Is one justified in neglecting his family on the ground of involvement in larger issues? Is it right for one to condemn one’s young children and ageing partners to poverty and starvation in the hope of saving the wretched multitudes of this world?” And to one of Winnie’s uncles, he writes that he could not bear to dwell much on his daughters with Winnie, Zeni (Zenani) and Zindzi (Zindziswa, whom he had last seen when she was less than two), because of the pain it caused him.

Zeni and Zindzi weren’t allowed to visit him until they turned 16 and so he tried to fulfil his parental duties through correspondence. Some of his letters to his children are among the most moving, though at times he turns into an old-fashioned patriarch. He writes sternly in 1970 to Makgatho, his second son by Evelyn, reproving him for his lack of pride, conscience, will or independence (although he does soften this criticism by blaming his own absence for his son’s fecklessness). In 1971 he tells Zeni, who had scribbled on the envelope “be like Elvis, go man, go”, that he hoped she was also listening to the music of Miriam Makeba, Paul Robeson or Beethoven. And in 1979 he advises Winnie to give Zindzi hot tea and Mandl’s paint with a throat brush for her bronchitis. And yet even from prison he realises when he sounds too overbearing. To Thembi’s widow, whom he has never met, he writes a letter full of advice that he tempers by saying, “Remember that whether or not you accept my advice will not in any way affect my attitude towards you. You are my daughter-in-law of whom I am very proud. You are dear to me.”

Death stalks these letters. “You have to be locked up in a prison cell,” he writes, “to appreciate the paralysing grief which seizes when death strikes close to you.” At the same time hindsight beats a future loss into the reader’s consciousness – that of his partnership with Winnie. Reading what she went through – her imprisonments (at one point she was held for 200 days without access to a shower), the attacks on her by the state and by persons unknown, her exile to godforsaken parts of the country – one cannot but feel for her. That she triumphed over her persecutors is a mark of her courage. And yet the costs are visible, both in Mandela’s letters and in what we now know about the end of their marriage. He wrote to her at the height of her troubles: “I feel as if I have been soaked in gall, every part of me, my flesh, bloodstream, bone & soul, so bitter am I to be completely powerless to help you,” and he wrote this knowing that she was persecuted because of her association with him.

He dreamed of her while he was in prison, and he wrote about those dreams. In 1970 he dreamed she was doing a “graceful Hawaiian dance”. “You whirled towards me,” he wrote, “with the enchanting smile that I miss so desperately.” But by 1981 the dreams were darker. In one of them, Winnie was walking, head down, searching for something. Driven to welcome her, he found to his disappointment that “I lost you in the ravines that cut deep into the valley & I only met you again when I returned to the cottage. This time the place was full of colleagues who deprived us of privacy.”

Well, now we know he did indeed lose her in the ravines, a sorrow that dogged his release. In 1962, she had sustained him by writing: “Nothing can be as valuable as being part & parcel of the formation of the history of a country.” With him, she helped make this history, but their marriage could not survive the hardship they had both endured.

In his condolence letter to the widow of Albert Luthuli, one-time president of the ANC, Mandela writes that “a great warrior” has “passed from the stage into history”. Thus, also, has Nelson Mandela passed. And yet through these compelling letters the thinking, feeling, loving man he was comes back to us.

• Gillian Slovo’s latest novel, Ten Days, is published by Canongate. The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela is published by Norton. To buy a copy for £17.49 (RRP £25) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News