Never mind Brexit, the real impact of rebel MPs will be on the next general election

The launch of the breakaway Independent Group did not have the auspicious start they had hoped for: the race row involving one of its MPs, Angela Smith, threatened to undermine the very point of their leaving Labour on a platform of fighting antisemitism.

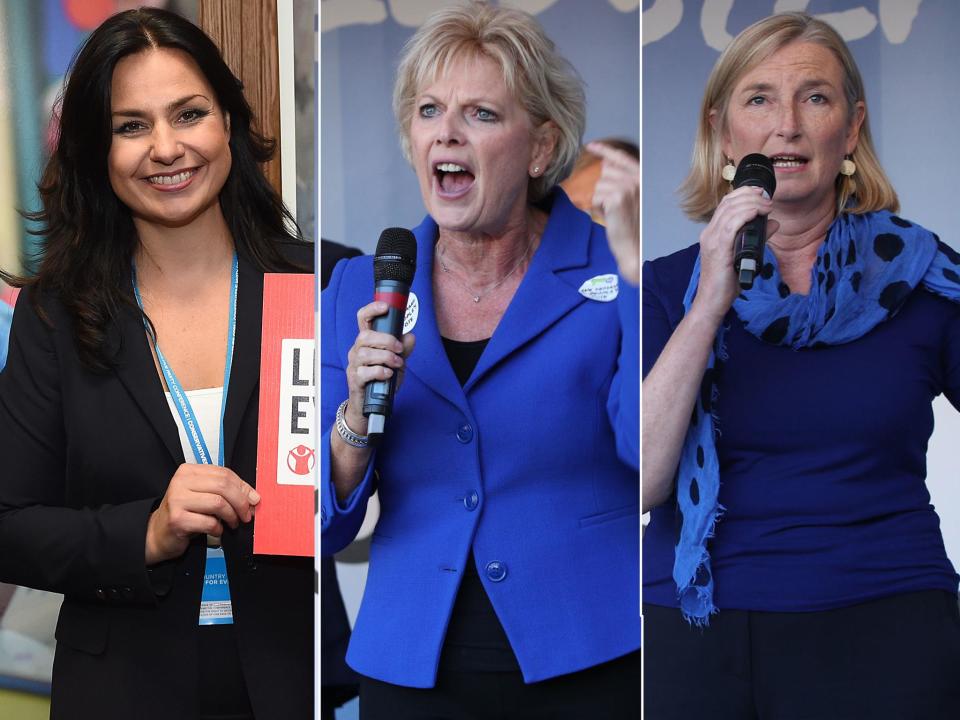

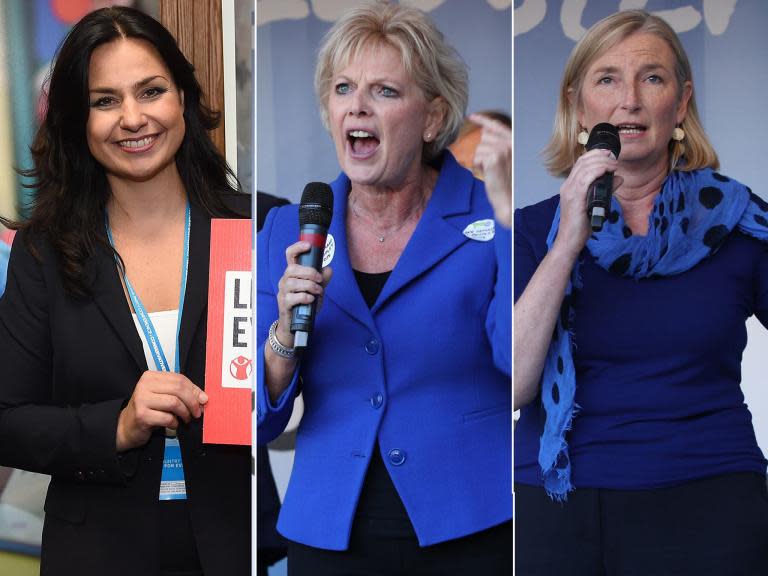

And so it follows that the next few days and weeks will be very messy. Now three Conservative MPs have quit, and there are likely to be more defections from Labour to come. Yet there is a bigger picture here: while there is still no party, leader or policy platform, the defections are just the start of a major realignment in British politics that will shape the next general election – in 2022 or earlier.

Early polling suggests a party that emerges from the Independent Group would pick up some support from voters – on Tuesday a Sky News Data poll put a centrist party on 10 per cent, third behind Labour and the Tories and ahead of the Liberal Democrats. Not enough to win many seats, let alone an election, but this is just a first poll and a foundation from which to build. So could they do better?

This depends on what happens next in both Labour and Conservative parties. The success or otherwise of a new movement will be influenced less by the person who ends up leading it and more by who succeeds Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn as leaders of their parties.

Right now, the political class is obsessed with how badly the prime minister and Labour leader are handling both Brexit and the internal troubles in their ranks. The launch of the Independent Group has sprung from May’s and Corbyn’s dragging of their parties further right and left and their failure to deal with nastier elements of, respectively, xenophobia and antisemitism in their midst.

May has already said she will step down before the next election, and it is possible that Corbyn, too, could move aside before 2022 to hold up the Labour vote. If their successors keep the two main parties firmly at the hard left and right of British politics, then the next election will be very interesting indeed for a newcomer.

Taking the Conservative Party first, it is likely that Boris Johnson could succeed May as prime minister, even by the end of this year. The former foreign secretary has re-emerged as the clear favourite with Tory grassroots and is in a stronger position in Westminster after his fellow Brexiteer Jacob Rees-Mogg started drumming up support for him among the European Research Group of Tory MPs. In a funny way, the defections of pro-Remain Conservative MPs make a Johnson leadership more likely, because their departure weakens opposition to him in the first stages of the contest.

A Johnson premiership would shape the course of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU throughout the transition period, making a harder Brexit trade deal more likely. In turn, this would compel many of those Tory supporters who voted Remain to turn away from the Conservatives and consider voting for a new party. This would also hold true if another Brexiteer, such as Michael Gove, won the leadership.

By contrast, if the next Tory leader is closer to the centre of the party – Amber Rudd or Jeremy Hunt, for example – the Conservatives’ broad support would hold up better on election day, and reduce the potential of a new party to steal votes from the Tories.

In Labour’s case, the prospects for a centrist party to pick up centre-left votes are even more clear-cut, given that, under Corbyn, the Labour membership is in his own image and therefore Corbyn’s successor will likely be from the same brand of politics. John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor, is in a strong position to succeed him. Of course, it is still possible that Corbyn will stay as leader to fight the next election – he has so far not indicated otherwise. In either case, Labour would remain firmly on the far left of politics and can expect to lose votes to a new political entity in the centre.

Yet the next Labour leader could emerge from the soft left of the party – someone like Angela Rayner or Lisa Nandy. If they decided to carry on where Corbyn left off, then the centrist party flourishes. But if they fight the election on a platform of reuniting all strands of left-wing politics, from centre-left to socialist, they could spike the guns of centrist party in the ballot box.

So too would MPs like Yvette Cooper and deputy leader Tom Watson, if either became leader – although given the nature of the Corbynite membership base, it would be unlikely they would succeed Corbyn.

These are arguments for the future, about a party that doesn’t yet exist. It is possible that those 11 MPs who have defected from Labour and the Tories lose their seats in forced by-elections, or on polling day itself. But if May and Corbyn’s successors continue to push their parties to the fringes of British politics, a centrist party could be the breakout force at the next election.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News