Newly-discovered planet more than three times bigger than Earth found orbiting Barnard's Star

Incredible footage shows a newly-discovered planet more than three times bigger than Earth which has been spotted orbiting the nearest single star to the Sun

The recently-discovered frozen world is a so-called super-Earth and is the second-closest known exoplanet to Earth.

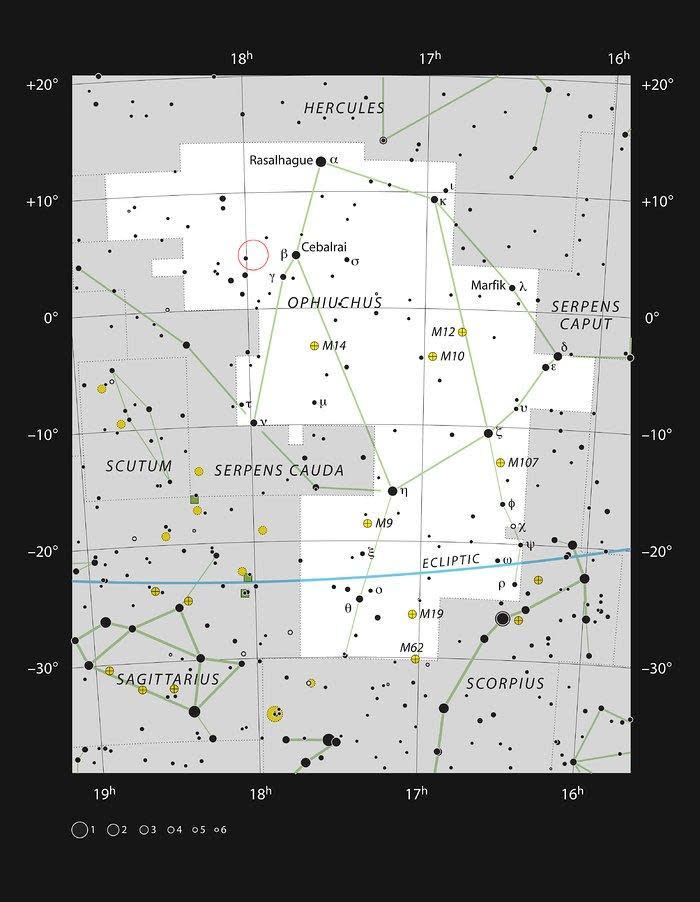

It orbits Barnard’s Star, the fastest moving star in the sky.

The discovery is a result of the Red Dots and CARMENES projects, whose search for local rocky planets has already uncovered a new world orbiting our nearest neighbour, Proxima Centauri.

Data gathered indicates that the planet could be a super-Earth, having a mass at least 3.2 times that of the Earth, which orbits its host star in roughly 233 days.

Barnard’s Star, the planet’s host star, is a red dwarf which only dimly illuminates this newly-discovered world.

Light from Barnard’s Star provides its planet with only 2% of the energy the Earth receives from the Sun.

Despite being relatively close to its parent star, the exoplanet sits close to the snow line, where volatile compounds such as water can condense into solid ice.

This freezing world could have a temperature of –170C, making it inhospitable for life as we know it.

Named for astronomer E. E. Barnard, Barnard’s Star is the closest single star to the Sun.

While the star itself is probably twice the age of our Sun and relatively inactive, it also has the fastest apparent motion of any star in the night sky.

Previous searches for a planet around Barnard’s Star have had disappointing results and this breakthrough was possible only by combining measurements from several high-precision instruments from a world-wide telescopes.

These include European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) HARPS instrument.

The project’s lead scientist Ignasi Ribas said: “After a very careful analysis, we are 99% confident that the planet is there.

"However, we’ll continue to observe this fast-moving star to exclude possible, but improbable, natural variations of the stellar brightness which could masquerade as a planet.”

The astronomers used the Doppler effect to find the exoplanet.

While the planet orbits the star, its gravitational pull causes the star to wobble.

When the star moves away from the Earth, its spectrum redshifts - it moves towards longer wavelengths.

Similarly, starlight is shifted towards shorter, bluer, wavelengths when the star moves towards Earth.

Astronomers take advantage of this effect to measure the changes in a star’s velocity due to an orbiting exoplanet with great accuracy.

HARPS can detect changes in the star’s velocity as small as 3.5kmph, which is about walking pace.

This approach to exoplanet hunting is known as the radial velocity method, and has never before been used to detect a similar super-Earth-type exoplanet in such a large orbit around its star.

Mr Ribas continued: “We used observations from seven different instruments, spanning 20 years of measurements, making this one of the largest and most extensive datasets ever used for precise radial velocity studies.

“The combination of all data led to a total of 771 measurements — a huge amount of information.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News