No Child Left Behind’s One Big Achievement?

Nearly two decades ago, when Ricki Sabia insisted her 5-year-old son could read, his public-school teachers didn’t believe her. He didn’t have a clear reading voice, Sabia explained, so they couldn’t understand him. “His expressive-language issues were a big barrier and caused inappropriately low expectations,” said Sabia, whose son, Steve, has Down syndrome. “It wasn’t until he started taking state assessments and far exceeding expectations that they started to take my observations about his abilities seriously and stopped trying to get him into special-ed classes.”

Sabia, a policy advisor for the National Down Syndrome Congress, is among the many disabilities advocates who are disappointed with Congress’s proposed rewrites of the law now known as No Child Left Behind, including the Senate’s widely touted Every Child Achieves Act. That’s because both the Senate and House versions, as they currently stand, would weaken federal provisions meant to track the academic progress of students with disabilities. These are students who, according to official data, account for 13 percent of America’s schoolchildren—and they are a diverse group. They may have physical impairments, such as hearing or visual defects; emotional challenges; or—accounting for the largest percentage of special-needs students—learning disabilities such as dyslexia.*

Recommended: How a Single Campus Cop Undermined Cincinnati's Police Reforms

The new bills—which still must be reconciled and signed by the president—would update the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the law on which No Child Left Behind is based. In part because of a burst of anti-federalism propelled by an unpredictable alliance of small-government conservatives, educators alarmed at the time annual tests take from other teaching, and anti-testing parents, the bills don’t prescribe any consequences for failing to comply with strict accountability provisions such as test-score benchmarks; those parameters would be up to individual states.

“The problem that students with disabilities face in schools is that people have such low expectations for what they can achieve.”

The prospective law would likely retain the same general testing requirements, but it could give schools and states more leeway to determine which students take the tests—and thus determine a school’s compliance with the state-determined accountability measures. Under No Child Left Behind, any school that didn’t test at least 95 percent of its students—and 95 percent of students in specific subgroups, such as minorities, English language learners, and special-needs children—faced severe sanctions, such as staff dismissals.

That 95-percent rule would probably stay in place, too, but amendments have been proposed on both the Senate and House versions that would essentially offer more flexibility to schools if parents decide to opt their kids out of tests. The Senate’s amendment would make it clear that the federal law wouldn’t supersede any local or state policies regarding parental opt-outs. That, in the House, would ensure schools aren’t penalized if opt-outs pull the test-taking rate below that 95 percent threshold—a move that opt-out advocates such as Diane Ravitch, the scholar and renowned education-policy analyst, are celebrating.

Recommended: White Flight Lives on in American Cities

* * *

Despite the sustained backlash against testing in communities from New York to Seattle, a sizable faction of parents and disabilities groups see the two proposals as a step backwards. Critics say the prospective amendments could create loopholes in which schools allow, or even encourage, parents of special-needs children and other struggling students to opt them out of testing. Strict federal mandates involving both testing and penalties for schools that don’t include students with disabilities, critics argue, ensure all kids are getting access to the mainstream curriculum alongside their general-education peers.

“Fundamentally, the problem that students with disabilities face in schools is that people have such low expectations for what they can achieve,” said Barbara Trader, the executive director of TASH, a prominent disabilities advocacy group. In being able to see how special-needs students’ test scores stack up against those of all their peers, teachers and parents can get an idea of how well or poorly special-education students are performing or being integrated into the general-education classroom, according to Trader. “It’s that ability to be held publicly accountable that allows parents and other stakeholders to ask questions.”

That’s not to say there’s consensus on the merits of No Child Left Behind for special-needs students. While disabilities advocacy organizations joined the NAACP and other civil-rights organizations earlier this year in urging Congress to keep those rigorous provisions, another faction of special-education teachers and researchers has long argued that annual testing harms students with emotional and learning disabilities.

Recommended: How Rich People Raise Rich Kids

Bianca Tanis, a special-education teacher in New York, says she’s witnessed children break down in tears—with one even banging his head on the table—during the standardized testing required by the current law. Determining if a student is learning solely based on test scores seems to be counter to the idea of inclusion, she argued. “One of the hallmarks of a child with a developmental or cognitive disability is that they don’t learn at the same pace [as their peers],” she said, referencing a term commonly used to describe reform-driven testing: “one size fits all.”

“One test score is not enough information to educate that kid.”

Rachel Lambert, an education professor at Chapman University, studied a New York City classroom for a year and witnessed a special-education student go from a top-performing math student to one of the least proficient when test prep time rolled around. “High-stakes testing narrows the curriculum for kids with disabilities. One test score is not enough information to educate that kid,” said Lambert, whose research on special-needs students and testing will be published in a forthcoming special issue of Teachers College Record, a leading academic journal.

Lots of educators are optimistic about the rewrites because they may take the classroom focus off test prep. “The problem is that the inferior, blunt state-level tests don’t deliver any kind of nuanced diagnostic assessment for any learner,” said Celia Oyler, an education professor at Columbia’s Teachers College, echoing disabilities advocates in noting that exclusion from the general-education classroom is an ongoing problem. But, she added, “the problem is access to the curriculum. The solution that some of these groups have hit on is the wrong solution.”

* * *

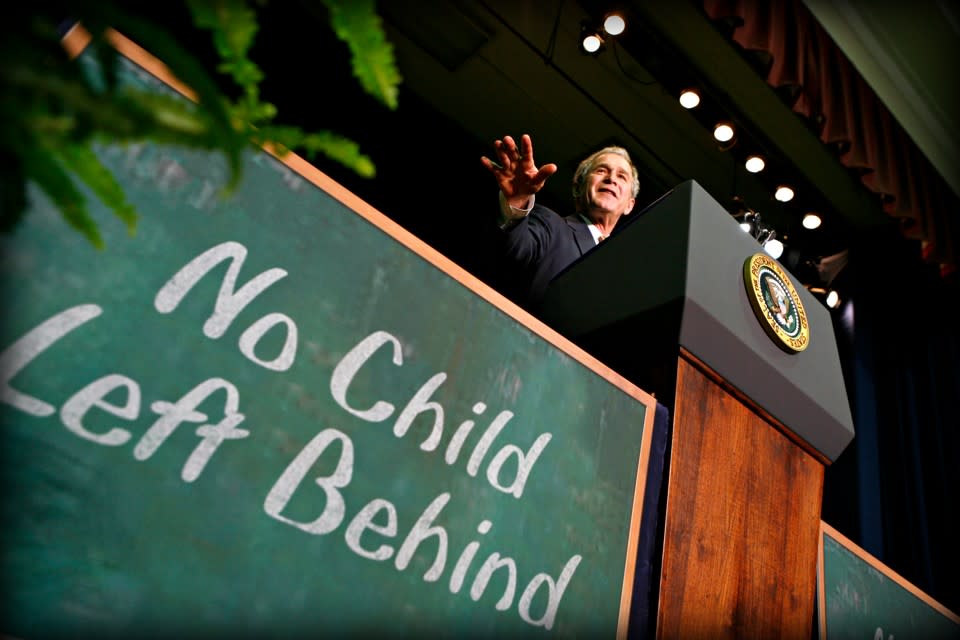

In 2001, No Child Left Behind famously ushered in the era of what George W. Bush often described as “high expectations.” The new policy required states to give rigorous annual tests to students in certain grades, provide specific reports on the test scores of historically underserved groups, and demonstrate that these students were progressing each year. (In edu-speak, students needed to achieve designated benchmarks known as AYP, or adequate yearly progress.)

The recent opt-out trend—in which thousands of (largely middle-class) parents and their children have boycotted new standardized exams—is in large part a reflection of how strenuous those mandates became. But some say it’s a double-edged sword in that it may be unintentionally undermining other kids’ achievement by depriving schools of specific test-score data needed to gauge the progress of student subgroups.

For some advocates, No Child Left Behind marked a new chapter in which kids with disabilities counted. Since 1990, the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) has required that students with disabilities be included in the “least restrictive environment”—that is, general-education classrooms—whenever possible. Later, No Child Left Behind, by stipulating transparency and sanctions for schools that failed to boost disadvantaged students’ achievement, served to measure whether IDEA was being put into action: whether disabled students were getting access to mainstream curricula and the tools they needed to master them. For the first time, “[special-education students] were part of the system and there would be interventions unless academic achievement improved,” said Andy Smarick of the nonprofit education consulting firm Bellwether Education Partners.

For some advocates, No Child Left Behind marked a new chapter in which kids with disabilities counted.

Now, disabilities advocates worry that the new proposals’ opt-out amendments—along with the ability of states to determine the consequences for schools that fail to comply with testing expectations—could allow schools to slide back into the ‘70s, when students with disabilities were often warehoused in special rooms and only one-fifth received a public education. (Some might recall the reporter Geraldo Rivera’s famous 1972 expose of New York’s Willowbrook School, which reveals students naked, some in their own filth, with overwhelmed aides and no instruction.) In some states and districts, that era may have never come to a close: Last week, the Department of Justice issued a letter to Georgia alleging that the state was violating the Americans with Disabilities Act by “unnecessarily segregating students with disabilities from their peers.”

Could the new law mean students with special needs may, once again, all but disappear on test days and end up back in their segregated learning environments? Pre-No Child Left Behind, some advocates argue, special-needs students were often asked to stay home or sit the test out, because it didn’t matter what percentage of them participated in the assessment.

These days, under federal law, students with disabilities get access to the general curriculum rather than, say, “life skills” classes. A blind student today needs a book in Braille, not a separate school; a student with an emotional disorder may require an aid in the same classroom, but while doing the same projects as his peers.

Related Story

Life After No Child Left Behind

Candace Cortiella of The Advocacy Institute, a nonprofit focused on special-education rights, fears that the potential loopholes in the new law could mean those students would be again relegated to second-rate educations. Cortiella said she and her colleagues are “disappointed” with the bills because they lack “any kind of real provision that require specific intervention activity to take place in low-performing schools.” If schools know they can let students with disabilities slide academically or exclude some lower-performing special education students from their overall testing data, perhaps they wouldn’t make an effort to integrate them with their better-performing peers.

Research shows that the outcomes of special-needs students have improved dramatically in the years since No Child Left Behind was implemented, and while it’s unclear how much of a role the law played in that trend, some data suggests that its rigorous accountability provisions may have been a factor. A study published earlier this year by the American Institutes for Research suggests that when states are subject to strict accountability provisions for students with disabilities, those students are transferred from special-education tracks into mainstream classrooms at higher rates. The last decade has seen an increasing number of special-education students graduate from high school: 68 percent received diplomas in 2011, compared to 57 percent in 2002, and the dropout rate has nearly been cut in half to just 19 percent. Meanwhile, 95 percent of students with disabilities are now educated in regular schools, compared to 20 percent in 1970. “We have so much history of how all these sub-groups are treated,” said Trader of TASH. “If the federal government does not have a role it will get worse.”

Today, Sabia’s son is 23 and has taken community-college classes. While he never scored “proficient” on Maryland exams, according to Sabia, he improved each year and was eventually included in general-education classrooms. “He never would have been this successful without strong academic skills and the confidence that comes with being integrated in all aspects of life, including general-education classrooms,” she said.

States are poised to regain a say over schools’ expectations, and to take a stance on the merits of high-stakes testing. Yet if states ignore the potential of a child with Down’s Syndrome to read, or fail to provide a child who cannot speak with technological aids so she can demonstrate her intellect, it may come to the feds again—this time through lawsuits.

* This article originally referred to autism as a type of learning disability. Autism is a developmental disability. We regret the error.Read more from The Atlantic:

This article was originally published on The Atlantic.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News