‘There is no longer a free press in Turkey’, says media tycoon Hamdi Akin Ipek

With as much composure as he can muster, Hamdi Akin Ipek is recounting how the Turkish government seized and shut down the newspapers he owns, took his television news channels off air and imprisoned the journalists who worked there.

“I was in London for work,” says the 54-year-old. “I opened my computer in the morning and saw what had happened.” He watched events unfold online. As protesters faced tear gas and water cannon, police used chainsaws to break through the gate at the Istanbul HQ of Koza-Ipek media group.

Inside, journalists were still working. The editor-in-chief of one channel, Bugün TV, told viewers: “Do not be surprised if you see police in our studio. This is an operation to silence dissident voices.”

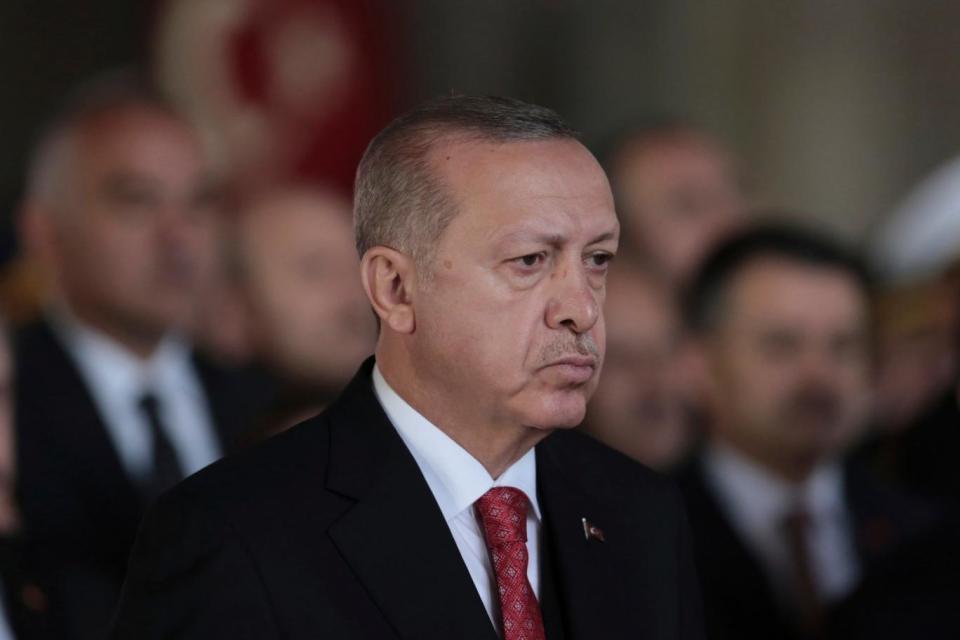

That was October 2015, days before a general election in which Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s party tightened its grip on power. Ipek has not been back to his homeland since. Instead, he is fighting an extradition request by the authorities in Ankara for him to face trial over the alleged funding of groups opposing the government.

At Westminster magistrates’ court last month, the request was rejected on the grounds that if he went back to Turkey, Ipek would be at risk of serious mis-treatment. Judge John Zani called Ankara’s bid “politically motivated”. The Turkish government has appealed and Ipek, who denies the allegations, is awaiting a hearing early next year.

The tycoon, who made his money in media and mining, says his assets have been frozen and his family’s passports revoked. He hasn’t seen his 73-year-old mother in more than three years and his brother is in prison.

The storming of Koza-Ipek was another stage of Erdogan’s crackdown on opponents. It gathered pace after July 2016, when the President crushed an attempted coup against him by elements of the armed forces.

In the past two years, at least 189 media outlets have been shut down and at least 319 journalists arrested — it is difficult to know the exact number, says Ipek, “because there is no longer a free press in Turkey”. Academics, teachers and civil servants have been jailed or sacked. The New York Times reports that since the coup the prison population has swelled by 50,000.

The government has also seized about $11 billion (£8.7 billion) of corporate assets — from small baklava chains to huge conglomerates.

More than 950 firms have been affected, with the government alleging they are linked to Fethullah Gülen, the Muslim cleric who Turkish leaders claim was behind the coup attempt. Ipek is accused of being part of Gülen’s movement, which he denies. Gülen, who lives in exile in the US, denies plotting the coup.

In this context, Turkey’s criticism of Saudi Arabia over the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi jars. “What happened to Khashoggi is unbelieveable and disgusting. It is ironic that Erdogan has used the Khashoggi murder in the way that he has, because Turkey is a jailer of journalists. Any publications or TV stations that try to be objective have been seized and either closed or turned into government propaganda outlets.”

Ipek believes the government “wanted to make an example” of him: “There is political motivation behind this wholly unmerited prosecution. I have not committed one single crime in my life, not even a traffic penalty. Now there are thousands in Turkey who do not have the ability to defend themselves. It is my responsibility to talk on behalf of them. If I cannot stand up for my journalists how am I going to run my business?”

When Erdogan was first elected President in 2014 — he had been prime minister since 2003 — Ipek says they got on. “He was presenting himself as democratic. He promised we were going to be part of the European community and everything would be different. We were happy. Then he started to put pressure on.

“Mr Erdogan asked to see me because there was a column in the paper written by a woman who said she was an atheist. I told Mr Erdogan I hope she’ll find the right way, but she doesn’t slander, she doesn’t lie. I cannot fire her. I cannot tell a journalist what to write.”

It was a TV interview that Ipek thinks made him a target. “I said, it is the government’s right to punish criminals, but it is not their right to punish the whole group. If an individual footballer committed a crime, you would not persecute their whole team.”

“The first thing tyrants attack is the free media because if they silence the media they can do whatever they want. The free media turns on the lights.” Now, in Turkey, “people are living without hope”. The latest victim is a journalist who made a documentary about the night of the coup. She asked questions and they threw her in jail. She has a daughter.”

Ipek says he wakes up every day “in a tragedy”. His address in London and car registration have been exposed on the internet and he has had death threats. “My daughters are at university here and I’m scared on behalf of them. I cannot imagine the future, I just think about the next day.” Should Londoners visit Turkey? “I don’t want to say. If they feel comfortable they should. Of course people should not forget Turkey. Journalists should shed light on this tragedy.”

@susannahbutter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News